The Yazidi massacre that took place as a result of the ISIS attack on Shengal on August 3, 2014, and what happened as a result of the massacre continues to be the subject of literary and artistic works.

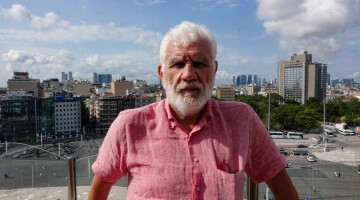

Italian journalist Sara Lucaroni went to Shengal after the attacks by ISIS. She is the author of the book "La luce di Singal. Viaggio nel genocidio degli Yazidi" (The Light of Shengal. Journey to the Yazidi Genocide).

Can you tell us about yourself ?

I am an Italian journalist and writer. I have written reports from Iraq, Syria and Turkey and investigation articles for L'Espresso, Avvenire, Domani, Speciale TG1, SkyTG24. I also work for TV2000, La7 and Rai3. I write about rights, legality, anti-fascism and have published three books, “The darkness under the uniform. Mysterious deaths among state servants” (2021), “Always him. Why Mussolini Never Dies” (2022) and the latest, “The light of Shengal” released a month ago.

Talking about “The Light of Shengal. Journey to the Yazidi Genocide", how did you decide to work on the Yazidis and the Senghal massacre, and what affected you the most?

When the Islamic State conquered the Nineveh plain, I was very struck by the images of the population fleeing to a mountain, the Mount Shengal, with nothing, on foot, desperate. That population was the Yazidis. It was August 2014. In October of the same year, while I was following the news of the war in Iraq and Syria from Italy and reading about the violence of Al Baghdadi's militiamen, a Yazidi boy I didn't know and had never heard of before called me from the top of that mountain to ask for help: they needed shoes for the children, it was cold, and they had been there since the summer. He was given my number from a friend we didn't know we had in common: Ali al Jabiri, an artist originally from Baghdad. With his relatives and the people of his village, this boy had formed a fighting group and helped as he could the families who were stuck up there. From that moment until today, I have been busy talking about this minority and the 74th genocide it was subjected to, and I was struck by its strong community spirit, but also by the idea of brotherhood between peoples, pacifism, tolerance.

In your book, you talk about the massacre carried out by ISIS and the experience of the Yazidi people. What sources did you use to research the book?

I only used direct sources. The book is a narrative report, and recounts my first trip to Shengal, a few months after receiving that phone call. In fact, when the necessary security measures were in place, I left to reach Iraqi Kurdistan and the fighting group thanks to which I had been able to describe the war against the Islamic State from the point of view of the Yazidis. I met village leaders, kidnapped women who had managed to escape, survivors of the massacres, religious men, refugees who lived in reception camps and who desperately tried to have news of their kidnapped mothers, sisters and daughters.

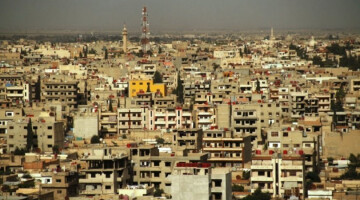

What were your first impressions in Shengal?

It was very difficult to live for twenty days in a reality of war and in very harsh desperation, but I was also grateful to those who welcomed me and allowed me to tell directly and in an in- depth way everything that the Yazidi population was experiencing. Everything was missing: 80% of the houses were destroyed, there were no hospitals, water, electricity, the roads were blocked. When I arrived, the mountain was clear on one side and Mosul, Shengal and Tal Afar were still occupied by the Islamic State. It was also quite dangerous because some Western journalists had been kidnapped. They had been beheaded and shown in videos, as propaganda. I had the Peshmerga and the Yazidi fighting group with whom I had worked in the previous months from Italy as an armed escort and I felt safe. But on a human level, to experience their tragic reality was very strong.

Can you give some information about the content of your book for those who haven't read it yet?

First of all, I can say that it is a fiction book and not an essay. I talk about the days of my work in Shengal, the meetings and interviews, life in the destroyed villages, the work of the fighting soldiers, the life of the few people who returned home, the life of the displaced, the violence against women in conflicts, the religion of the Yazidis and their traditions, the birth, the ideology of death of the Islamic State, the complex background of the 2003 war in Iraq. And then there are the behind the scenes of the work of a journalist who reports on a conflict, the emotions, the mistakes, the tears, the doubts of this profession.

Do you think that the Yazidis, who have historically faced many massacres and genocides, have been abandoned to their fate and left alone by the international community?

Yes. Suffice it to say that no one has condemned the perpetrators of the crimes against Yazidi women and men. Only Germany has issued two convictions against two former members of the Islamic State for war crimes and crimes against humanity. But most of the mercenaries are in prisons controlled by the Kurds and their wives and children are in the Al Hol camp in Syria, and many Western states only repatriate their citizens, who are criminals, through very slow bureaucracy. In addition, there are mass graves still to be dug in Shengal: ten years have passed. There are more than 2000 people abducted, of whom nothing is known. They are still missing, and too few families have been able to return home. Only some NGOs and foundations have done something concrete for reconstruction. But it's all too little.

Although the people of Shengal demand an autonomous administration, this demand is constantly rejected. As someone who follows the events closely, why do you think it is important for Shengal to gain an autonomous structure?

Many Yazidis tell me they don't know where they can get a document, such as a passport or identity card. The civil war of 2003, and then al Baghdadi's jihadists, destroyed the social fabric and left only fear and mistrust between communities. This is a very serious issue. And then there is the real problem: the territory of Shengal is strategic and everyone wants to plant their flag there. Shengal must belong to those who inhabited it and lived there for hundreds of thousands of years: the Yazidis and all the minorities of the Nineveh plain. They must be able to decide their destiny autonomously, without conditioning and without external influences. They must finally have political weight. Someone spoke of a protectorate under UN auspices. I don't know if this is a solution, given the recent failures of humanitarian law in Gaza.

As you know, one of the places targeted by the Turkish state is Shengal. How should we evaluate the Turkish state's attacks in this region?

Turkey is very dangerous, it plays on many tables and never gives any political guarantees: it considers the PKK an enemy to be defeated at all costs and does not even stop before the civilian population, like the many Yazidis who did not embrace the cause in Shengal of no party or armed group. This is a problem and the solution isn't coming anytime soon.

As you know, Kurds, especially the PKK, played an important role in the military defeat of ISIS in Shengal and Syria. Considering the current stage, what would you like to say about this?

PKK-linked militias were instrumental in the defeat of the Islamic State. They were heroic, on the battlefield and even afterward, in the phase of maintaining security. Yet they continue to be betrayed by all actors operating in the Middle East. And, unfortunately, now they alone once again carry all the colossal weight of the dream of seeing their autonomous and independent territory recognised. This is one of the numerous injustices of history and is one of the consequences of the infinite evil that the Western colonial spirit has inflicted on those lands.