In the prisons of Northern Syria thousands of members of the jihadist militia "Islamic State" (ISIS) are waiting for their trial - about a fifth of them from abroad. For years the autonomous administration has been calling on their home countries to take them back and bring them to trial. But many countries refuse to take responsibility for their nationals. An international special court, as proposed by the North-East Syrian autonomous administration authorities, also seems to be a long way off. And so the ISIS prisoners remain in prisons in northern Syria for the time being - and wait.

The situation in the prisons for ISIS members is tense due to the years of uncertainty about the legal dispute with them. This situation creates new problems. In addition, the resources of the self-government are scarce and the prisoners can only be adequately cared for. Furthermore, there is a lack of possibilities to build more prisons. Because of the overcrowding of the internment camps, riots are also threatening.

ANF reporters visited the two prisons in northern Syria that are most affected by overcrowding and got an idea of the situation. All prisons in the autonomous region are run by the self-government and guarded by the Internal Security and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). The number of inmates is in the thousands. We were also able to talk to some of the prisoners.

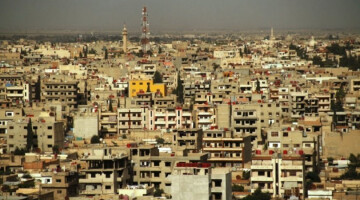

Central prison of Hesekê

The first prison we visited was the central prison of Hesekê. It was built by the international anti-ISIS coalition when problems with the accommodation of the ISIS prisoners became more acute. Around 4,000 prisoners are held here - many of them former FSA mercenaries or members of the Al-Qaeda branch Jabhat al-Nusra. The majority, however, are ISIS jihadists. They come mainly from Iraq and Syria.

Some of them have been convicted by the "People's Defence Courts" (Kurd. Dadgeha Parastina Gel) established in Rojava in 2014. Besides single cells, there are several large cells for up to 50 prisoners. Almost all jihadists we spoke with said that they were satisfied with the system and prison conditions and were treated humanely. Visits from relatives are also possible. Every day, three prisoners cook food for the detention centre together with three cooks and distribute it under the control of security forces.

Prisoners do not admit their crimes

Except for the already convicted jihadists, whose crimes have been proven beyond doubt, almost all of them claim to have lived only under ISIS rule and have committed no crime. For this reason, intensive work is being carried out to follow up evidence and proof of crimes in which these persons may have been involved. Among the group denying their crimes are Iraqi ISIS members Ahmad Taleb Mansour and his father Mansour al-Huwaidi al-Shammari. Both are incarcerated in the same cell. The son is accused of being one of the executioners of the ISIS. He denies this and claims to have worked in food distribution at the ISIS. However, the charges against him are backed by strong evidence. There are even videos showing him performing executions. In court he claimed to have executed "only" one person. The Dadgeha Parastina Gel sentenced Mansour to life imprisonment for "crimes against humanity".

Many continue to defend their crimes

Even though some of the prisoners claim to regret their affiliation with the ISIS, the overwhelming majority expresses their continued adherence to the ISIS ideology. Many are convinced that this ideology will liberate them. One prisoner we talked to is Hadir Shaid al-Uthman from Iraq. According to his own statements, he joined the ISIS in 2015 and actively fought for the organization. He says he is satisfied with the prison conditions here. In Iraqi prisons, however, there is massive repression. Uthman says, "If I'm extradited to Iraq, I will kill myself first." When asked if he regrets being part of an organization like the ISIS that committed crimes against humanity and other atrocities, he first replies: "We did not commit atrocities. When we point out the evidence and the Shengal genocide, he says: "Sharia law demands it that way for the unbelievers."

Another prisoner, Ashraf Ahmed Vahad from Deir ez-Zor, we met at the yard gate. He joined the FSA in 2013. In a skirmish with ISIS members, he was captured by the militia. Eight months later he decided to join the ISIS. He surrendered to the SDF in 2017. Vahad tells: "I have deeply regretted joining the ISIS. I surrendered to the SDF because I learned that they do not treat captured ISIS members in any kind of inhumanity. I want to serve my sentence and become a normal person again. The treatment in prison is humane. There is no oppression whatsoever."

Serious risks

We drive from Hesekê prison to another prison, where mainly ISIS jihadists from the last ISIS enclave al-Bagouz are imprisoned. When the East Syrian village fell in March 2019, masses of ISIS jihadists surrendered to the SDF. They were imprisoned in a part of the University of Hesekê that had been converted into a prison. With around 5,000 prisoners, it is now the most overcrowded prison in the entire autonomous region of Northern and Eastern Syria. The prison conditions are extreme.

The building is old and dilapidated, it does not look particularly safe. In some cells there are hundreds of prisoners, in others even 150. The infirmary is also bursting at the seams. The overcrowding brings with it various health and safety risks. At the top of these problems is the reorganization of the ISIS among the prisoners and the rapid spread of diseases. Especially in prisons, pathogens find ideal conditions for spreading. Unless the capacity of the prison is increased or prisoners are transferred to other prisons, risks such as mass escapes and riots are inevitable.

In the past, there have already been organized riot attempts in some cells here and in the infirmary. There have also been attacks on prison staff and journalists. For this reason, those responsible refuse us access to the infirmary or the cells. We take pictures through the small windows in the cell doors. The meetings with the prisoners are held in a room specially provided by the prison management.

For the ISIS - until the last moment

The majority of those we met deny having been with the ISIS. They said they had "emigrated" only to areas under ISIS control. Although they have adopted the ideas of the terrorist organization, they blame the functionaries. They complain that they were left alone under the bombs while their leaders fled to Turkey or Europe. However, the leaders of the SDF state that the jihadists imprisoned here have actively fought until the moment of their release.

We also talked to ISIS member Rıdvan Genç from the Turkish city of Afyon. He claims to have joined a Salafist community in Ankara and then travelled to the ISIS area so that his children could learn Arabic. Genç claims to have worked only as a car mechanic. Pointing out the crimes against humanity and especially against women, the murderous ISIS thought is very clear. He replies: "If it is religiously legitimate, then it will be done. Faith is above conscience."

Why does nobody take responsibility?

Abdullah Numan is a Belgian citizen with Moroccan roots. He is one of the few people who admit at least some of the crimes committed. Asked about threatening videos against Belgium in which he appeared, he relativizes: "At that time I was using narcotics, I wasn't in my right mind." The routes from all parts of the world had been open to join the ISIS in Syria, explains Numan. "Turkish intelligence knew I was interested in such communities. Although my name was known, I was not stopped when I crossed the border. I went to Germany and from there I travelled on to Turkey by plane. I crossed the border in Antep. There were soldiers on both sides, but nobody did anything." Numan demands a trial before a Belgian court: "We have virtually been cleared the way for our accession and even encouraged. Now no responsibility is being taken for us. We have committed crimes. They should give us our punishment and we will accept it."

Young people are becoming more radicalised

55-year-old ISIS jihadist Fatih Çiftçi comes from Istanbul. There he lived in the district of Bağcılar, where he was also an active member of a community. He emigrated to the ISIS with his entire family. The border crossing to Syria was unproblematic, he recalls. He surrendered to the SDF "in good conscience", he says. "There is no torture or supply problems here. A humane approach is paramount. But the prison is simply overcrowded. We have a lack of space and problems with medical care. Our biggest problem is that we don't know what's coming. We don't have the slightest idea of what is going on in the world. This situation is having a very drastic effect. Not everyone is as old as me. There are young people among us who don't know how to live together. They don't know how to obey. The other day, they started a riot in our cell.

We should be judged. Everyone should be punished for his crime and transferred. We lived in this country and when a crime was committed, it was committed here. The evidence is here on the ground, so we should be on trial here too. The world must deal with this problem and help the autonomous self-government to solve this problem."

The power of autonomous self-government is exhausted

Both those responsible and the prisoners we spoke to unanimously emphasize that the trials must begin immediately. The prison management emphasises that the isolation that has now lasted for a year, the lack of opportunities for self-government, the lack of procedures and the insecurity that this has created are further radicalising the prisoners.

The demands of the North-East Syrian autonomous administration sound the same. The trials of ISIS jihadists who have committed crimes against humanity are the responsibility of all humanity. But those responsible also say that they do not have sufficient means to guarantee the everyday needs and guarding of the prisoners. And they warn that failure to address this problem will encourage even greater radicalisation.