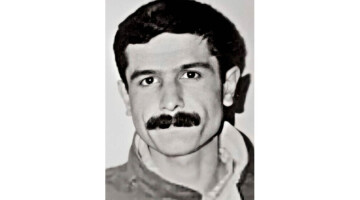

Santiago Alba Rico is a Spanish philosopher, writer and essayist. He studied philosophy at the Complutense University of Madrid. In the 1980’s, he worked as screenwriter for the universally popular television programme La bola de cristal. He published around twenty books on politics, philosophy and literature, as well as three stories for children and a play.

We spoke to him about the coronavirus emergency and its effect on people, governments, economy and about what to expect from the future.

When analysing the current situation, one of Hans Christian Andersen’ most famous story comes to mind "The Emperor’s new clothes"…Who is naked, the states? Capitalism? Us?

I think it serves to make us realize that we are the naked one. I am referring to all humans, but above all to Europeans, who thought we were better protected, even under governments that we criticized or that seemed not quite enough democratic. On one hand, if you like, we have discovered the “human condition”, the common condition that unites us to all those distant dead that we only saw on television. That is the condition of radical fragility from which we considered ourselves liberated or that we – deluded - considered “overcome” thanks to our markets, our technology and our science. We have rediscovered the body: its slowness, its gravity, its anchorage on death.

On the other hand, we have discovered to what extent, in recent years, while we believed ourselves to be well dressed, neoliberalism has left us naked: with worse health, with fewer rights, with more social vulnerability. In the coronavirus emergency, the human condition and the social condition converge in a tragic way: it reveals at the same time a universal weather inclemency and an interested and concrete humanicidal policy.

How do you assess the responses of governments to this health emergency? What do they tell us about the current state of politics?

Uneven, late and uncoordinated. Each government has reacted according to its ideological nature. Beyond the negationist madness seen in in Mexico or Nicaragua, or the totalitarian one, such as that of Duterte’s Philippines – we have seen two conflicting models of State: one is that of the governments that have tried to reconcile the economy with protection of the health of citizens and the other is that of governments that, like that of Trump, Johnson or Bolsonaro, made it clear from the beginning (although they have later partially reversed) that the economy is above the health of citizens.

The most worrying thing, as a European, is to see that the EU countries, which fall in the first category, have been unable to coordinate their measures. After the English Brexit, the coronavirus crisis has produced a kind of widespread Brexit; in fact, the EU, which has revealed all its national tensions and selfishness, is ceasing to exist, which further reinforces those falsely “sovereignist” positions, both on the right and on the left, which take advantage of the tragedy to propose national contractions very centralists or jacobines - which, in my opinion, are enormously dangerous.

The EU, however, must be aware that, if it does not review itself, its internal relations and its unequal economic model, it will be responsible for its own death, and for the strengthening of authoritarian nationalisms already embryonically present before the crisis.

How do you value the reactions of people, of the communities to this invisible "enemy"? There are different reactions in that part of the world that believed to be "safe" and today suddenly finds itself in a position of total vulnerability and the part of the world that resists real and concrete enemies every day.

People arrive at common crises already configured or formatted in terms of class, education, history, biography. All these factors are momentarily suspended in any state of collective exception - catastrophes, revolutions, etc. - but they return when excitement and the affective community give way to regularities and routines, especially if those routines are also exceptional. There are areas of the world, of course, where that exception is so normal - famine or war - that communities do not remember anything before that and organize their lives around bare survival. This is not the case in Europe. We come from a rather fictional normality, presided by technological speed, accelerated consumption and "mass hedonism", very much dissolving social ties, and long confinement can generate much frustration and nihilistic rage after this first phase in which - I believe that - the excitement of the exception has been accompanied by a feeling of relief: that normality - which is also inseparable from job insecurity and urban solitude – was a burden and actually stressed us out.

Can we hope that this condition which is affecting everyone (even though with many differences) will help developing a different solidarity among people?

We should take advantage of that initial moment of relief to build a subject and an alternative. It is not easy, because the confinement itself leaves no other sociability than the balconies - while promoting very intense, and inevitable, communication through the same social networks that, somehow, without knowing it, we had grown tired of.

But in this initial relief - that of our fictional normality interrupted by the tragedy - we should look for another model, based on the relative optimism to which this scattered emergence of spontaneous solidarity invites us. If capitalism, as Kafka said, is "a state of the world and a state of the soul", the coronavirus shows us that neither the world nor the soul were already "finished", in an architectural and building sense. And this gives certain hope.

What future can we imagine after the "storm", especially in terms of what alternatives the left will (or won’t) be able to propose, since it does not seem possible (nor desirable) to return to the "normality" of the past.

The virus and the measures which go with it are in fact an immanence and, from the inside of an immanence, it is very difficult to imagine the outside. I will say what everyone knows. Three things can happen. One, we recover the previous fictional normality with a not improbable exercise of collective amnesia, with invariable economic patterns, although in a battered social situation. Two, capitalism breaks up and adopts very authoritarian national forms. Three, there will be new international agreements to create new institutions or to use existing ones in favour of truly social democratic policies that combat inequalities, ensure a citizen's income and guarantee access to health, housing, education, etc., preserving and deepening civil rights, which are being further eroded. Whether it is this last option that prevails - the most radical that can be imagined right now and not at all the most likely - will depend on the proposals and the pressures that are made from citizen collectives and citizens themselves.

To what extent this emergency is causing situations of authoritarianism (as in the case of Hungary), and also "temporary" limitations in terms of freedoms and rights that risk to become permanent, once the state of exception ends.

We like to talk about the “opportunity” that this crisis represents for the anti-capitalist and environmental consciousness, but we must not forget that every crisis represents an opportunity also for the most powerful, who have more means to take advantage of the crisis. The states of exception decreed in almost the whole world, and the massive use of technology for both virus and population control, are becoming “natural” without much resistance - because in confinement we also depend on technology to maintain contact with the outside world. They are becoming natural, moreover, in a world in which democracy has been receding very quickly. Head of states such as Orban, Duterte, or Berdimuhamedow may seem more or less exotic or peripheral, but they actually anticipate a global process that was already in the making. In this sense, the prestige of China, which emerges as victorious in this crisis, should indeed concern us.

The virus, together with common fragility and reciprocal solidarity, has generated a radical fear that demands something impossible: Total Security. This utopia of Total Security, indeed very dangerous, can translate into political-technological dystopias - also identitarian and nationalistic - that we should fight, at institutional, collective and personal levels, while the confinement lasts.

It is now more important than ever to defend the democratic character of our governments in Europe.