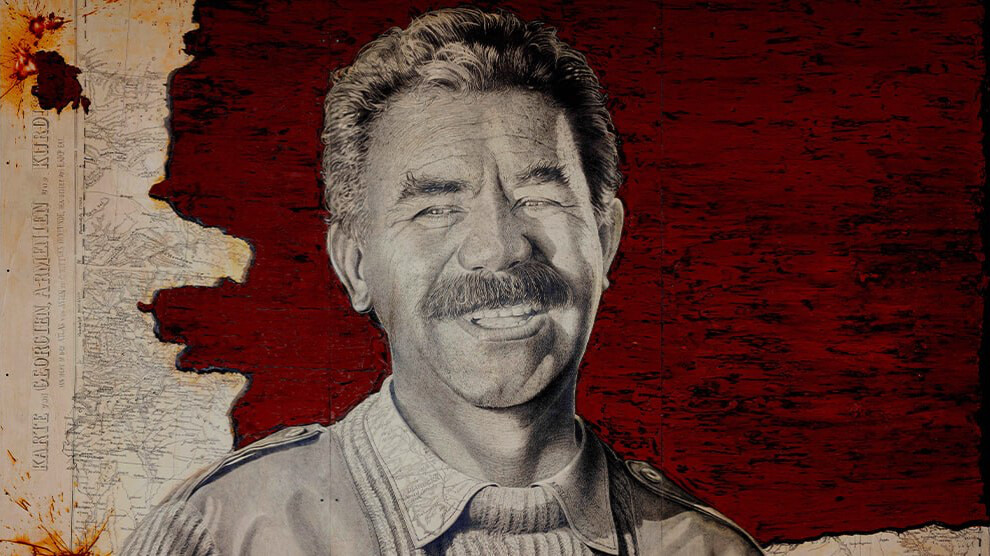

“When it is necessary, when their existence is at stake, when they are faced with the loss of their freedom and their dignity, it is inevitable for the peoples to resist. No method other than resistance can lead to the preservation of their existence, their freedom, and their dignity. The resistance in Kurdistan was a method of defending existence even before freedom and liberation.” Abdullah Öcalan (*)

What kind of oppression, assimilation, annihilation, and denial is necessary to bring a person or a collective society to the point of denying its own existence? Think about what has been done to a society like the Kurdish one to make them ashamed and even afraid of their own identity. I am not asking for sympathy, I just want you to think about it for a moment. Life in the region historically known as Kurdistan and inhabited by a majority of Kurds, especially that within the borders of the Republic of Turkey founded in 1923, is subject to a monistic state doctrine (enshrined in the constitution) that denies anything that deviates from Turkishness. It goes without saying that a social collective, in this case Kurdish society, cannot simply accept and endure such a situation.

Thus Abdullah Öcalan began his legitimate struggle in the 1970s against this historical injustice and tyranny. The legitimacy of these endeavours is also enshrined in the preamble to the UN Charter of Human Rights, which explicitly mentions the right to revolt against tyranny and oppression as a last resort. With the founding of the Kurdistan Workers‘ Party (PKK) on 27 November 1978, the struggle to overcome the annihilation and denial of the Kurdish people began. In 1984, a guerrilla war began that was supported by millions of Kurds, who placed in it their hope for change.

Despite all the difficulties and the war of annihilation waged by NATO’s second largest army, this struggle has continued unabated for 47 years. Since then, the Kurdish people have been waging a just resistance struggle for a dignified life. Tens of thousands have sacrificed their lives for these ideals. No one has the right to blame the Kurds for their struggle or demand remorse from them. On the contrary, the Turkish state must come to terms with its past of persecution and oppression and apologise to the Kurdish people. However, this is an important step that should be taken when the conditions are right.

In a historic appeal on 27 February 2025, Abdullah Öcalan, the leader of the PKK and undoubtedly its most politically significant prisoner, called on the PKK to lay down its arms, convene a congress, and decide to dissolve itself. This call made waves and led to intensive discussions in Turkey and around the world.

Öcalan’s appeal on 27 February is the result of months of mediation, several meetings with Öcalan and letters and talks held by a delegation from the Peoples‘ Equality and Democracy Party (DEM Party) with various political actors in the conflict.

Although the laying down of arms was made a condition by the Turkish government under R. T. Erdoğan, the search for a solution to this problem, which Abdullah Öcalan described as a “Gordian knot”, has a long history. The founding of the PKK in 1978 and the start of the armed struggle in 1984 are not a cause, but a consequence of the Turkish state’s policy of denial and assimilation.

It is generally accepted that this policy is the reason for the enormous support of Kurdish society for the PKK resistance. The years in which the PKK emerged, coincided with a period of numerous national liberation struggles worldwide. It developed with a socialist party programme and was influenced by the national liberation struggles of the time. It set itself the goal of establishing a nation state based on the peoples‘ right to self-determination. In his most recent appeal, Öcalan explained that this objective was also strongly influenced by actually existing socialism, which was very present internationally at the time. However, the armed struggle that began in 1984 gained decisive influence when actually existing socialism collapsed. However, the PKK was not weakened by the end of actually existing socialism but retained its social base and support. It was even able to expand it by placing the path to a more society-oriented democratic socialism at the centre of its struggle due to its criticism of state-led actually existing socialism.

With the first ceasefire in 1993, Öcalan and the PKK (via various mediators) sought a political solution with Turkish President Turgut Özal, who was also trying to find a solution. However, Özal died under suspicious circumstances on the very day that he wanted to respond to the ceasefire. The efforts towards a ceasefire and a solution were obviously sabotaged. In this vacuum, the conflict was once again shifted to military approaches by Turkey’s political leaders. In the years that followed, labelled the “dirty war”, it came to developments that caused much destruction. Turkey was taken over by military policy and Turkish society was intimidated under the guise of “security policy”. In order to deprive the PKK of social support, more than 4,000 Kurdish villages were destroyed by the Turkish military in the 1990s. Thousands of “unsolved”(Turkish: faili meçul) murders were committed and millions of Kurds were driven to Europe and the metropolises of Turkey through systematic ethnic cleansing. Numerous massacres, rapes, cases of torture, and arrests can be found in the documents of human rights organisations such as the IHD. Turkish society’s grappling with the consequences of this dirty war, which was waged in its name, is one of the steps towards a political solution. For these demeaning and inhumane practices against the Kurds were carried out by the military, police, and paramilitary forces of the state amid widespread silence of Turkish society.

Nevertheless, the Kurdish question could not be solved. The NATO member state Turkey and its military apparatus were able to gain the upper hand with international NATO support. All possible concessions of a political, economic, and geo-strategic nature were made. In return, the PKK’s resistance struggle was criminalised in many countries and demonised by being listed as a terrorist organisation (in the USA and in 2002 in the EU). The international community viewed the PKK solely through the lens of Turkish nationalism. The truth was distorted beyond recognition by systematic agitation and anti-propaganda in the media and politics, victims were turned into perpetrators and perpetrators into victims. Nevertheless, Öcalan persisted in his search for contacts in Turkish politics. He tried with great perseverance to solve the problem with political and peaceful means. When this failed, he even tried to bring the matter to the international stage. Before he was abducted to Turkey on 15 February 1999 as part of an international conspiracy by NATO members and countries such as the USA, Israel, Greece, Kenya, Turkey and their secret services in Kenya, he spent months in Italy and thus in Europe in search of international support for a political solution.

Anyone in Turkey and the rest of the world who believed that the PKK and Öcalan would be weakened by the conspiracy of his abduction and isolation on the prison island of Imrali was sorely mistaken. On the contrary, the PKK, as the pioneer of the liberation struggle in Kurdistan, has gained influence and persuasive power on the basis of the ideological, theoretical, and political foundation created by Öcalan, which can also be read in Öcalan’s prison writings.

By criticising the destructive nature of capitalist modernity, Öcalan developed a counter-project, constructive democratic modernity. With the project of democratic confederalism (based on democratic socialism), he showed perspectives and solutions for the creation of a democratic, ecological society centred on women’s freedom. The Kurdish women’s movement plays a decisive role in the implementation of democratic confederalism wherever it is organised. Öcalan’s formula “Jin, Jiyan, Azadî”, which runs through all his defence writings, stands not only for resistance, but also for the will, the strength, and the organisation to build a new democratic system beyond patriarchy under the leadership of women. In mid-September 2022, Kurdish women, who were later joined by tens of thousands of women in Iran, began a protest movement that caused a worldwide sensation. The multi-ethnic and multi-religious Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (DAANES) is also modelled on Öcalan’s ideas and theoretical framework.

As a result, he continues to influence not only millions of Kurds and numerous political parties and movements in Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran, but also offers democratic solutions for the entire conflict-ridden Middle East and for wherever oppression prevails. History shows that equating the right to self-determination with the establishment of a new nation state does not lead to a solution but only adds to the existing problems. The current conflicts, which must be seen as part of the Third World War taking place today, do not need more weapons and violence, but dialogue as the basis for the space of democratic politics. The realisation of freedom, equality, and democracy in Kurdistan, as in other regions, does not require new borders, but the softening and overcoming of these borders. It is not the state that should dominate and control society, as is the case in Turkey and many other centralised nation states, but the other way round: if society develops a democratic consciousness and democratic structures, it can also democratically control the state. Therefore, a democratic and peaceful development is also an opportunity for Turkish society to control its state through democratisation and democratic structures. As such, Öcalan’s compromise of “democracy plus the state as a general public authority” could serve as a future basis for Kurds and Turks to live in the same region without mutual marginalisation.

Against this backdrop, the call of 27 February is not a surprise, but the expression of a decades-long search for a democratic solution. Öcalan further writes in his statement: “The PKK, the longest and most extensive insurgency and armed movement in the history of the Republic, found a social base and support and was primarily inspired by the fact that the channels of democratic politics were closed.” And if today, after years of resistance, the PKK and its weapons are an obstacle to „opening the channels of democratic politics“, then the Kurdish liberation struggle is also in a position to overcome this obstacle. This is because Öcalan and the PKK are taking away from the Turkish state the reason and thus the “weapon“”or pretext to ignore a just, peaceful, and democratic solution or to delay it for tactical reasons or political calculation, as was the case of the first ceasefire mentioned above and the last dialogue process in 2012-2015. At the latest after Öcalan’s call, the ball is now in the Turkish state’s court. Öcalan has tied his demand to one condition: “Undoubtedly, the laying down of arms and the dissolution of the PKK require democratic politics and the recognition of the legal basis in practice.”

Öcalan shows the maturity of his liberation struggle: if necessary to discontinue its previous methods, armed struggle and the party (PKK), and to lead it in a new form under democratically developed conditions. It is therefore not a question of ending the liberation struggle, but of changing its means and form accordingly.

The PKK agrees with Abdullah Öcalan’s call for peace and announced a ceasefire on 1 March. It declared: “we agree with the content of the call as it is and we say that we will follow and implement it.”

The PKK convened its 12th party congress between 5 and 7 May under extremely difficult conditions. Due to massive Turkish attacks, 232 delegates gathered at two different locations. The PKK declared that it has successfully achieved its historic mission, having “dismantled the policies of denial and annihilation”. The Kurdish question could now be solved through democratic politics. Therefore, the congress decided “to dissolve the PKK’s organisational structure and end the armed struggle”.

Let us return to Öcalan’s prison writings: for example, the book Beyond State, Power and Violence, published in 2004, in which he develops possible solutions. In it, he proposes a redefinition of the understanding of the state that prevails in Turkey and throughout Kurdistan. “It would be better to agree on a lean state that only fulfils tasks to protect internal and external security and to provide social security systems. Such an understanding of the state no longer has anything in common with the authoritarian character of the classical state but would correspond to the character of a social authority.” In a newly defined democratic Republic of Turkey, the Kurds would enjoy all civil rights and freedoms. A democratic space could thus be created in which a democratic society (Turks, Kurds, and other ethnic groups in the same country) could realise their identity under constitutional law. In the same book (which is also emphasised in the current appeal), Öcalan adds: “For the Kurds to recognise the republic as a people, the republic must recognise them as a cultural group and as holders of political rights. Recognition must therefore be mutual and based on legal guarantees.”

The PKK made it clear that the congress decision did not herald an end, but a new stage in the struggle for freedom, democracy, and socialism. The declaration states that the Kurdish people, especially women and youth, will take on the tasks of the new phase of democratic struggle and self-organisation for the creation of a democratic society.

In order to implement the congress resolutions, Abdullah Öcalan must lead the peace processes. His right to participate in democratic politics and corresponding legal guarantees must be recognised. At the same time, the participation of parliament, extra-parliamentary forces, and social movements is crucial for the peace process. The release of Abdullah Öcalan would therefore be one of the most important steps in accelerating this process.

This means that the practical implementation of these resolutions cannot be achieved with Turkey’s current legal system, its anti-democratic understanding, autocratic and arbitrary governments with their anti-terror laws and political instrumentalisation of the judiciary. Rapid changes are needed in politics, the legal system, and society. Recognising the Kurds and other ethnic and religious identities living in Turkey requires democracy, political awareness, and justice. If the Turkish state and Turkish society carry out the democratic transformation and change envisioned by Öcalan, they will also become “democratic”, something they have renounced since their foundation.

After years of isolation and 26 years in prison, Öcalan’s latest appeal proves once again that he is still the key figure for a just solution in Turkey, a process which will also have great influence in the region. On an international level, representatives of the UN, the USA, the EU, the United Kingdom, Germany, and many other countries emphasised in their statements the importance of Öcalan’s appeal and the subsequent resolutions of the PKK as steps towards a solution to the Kurdish question. But statements alone are not enough. Instead, Turkey must be encouraged to democratise and find a peaceful solution. In Turkey, the reactions to Öcalan’s call so far from political representatives, including President Erdogan and his government partner Devlet Bahçeli, the leader of the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), but also representatives of the largest opposition party, the Republican People’s Party (CHP), contain positive signals.

In this context, Bahçeli issued a statement on 18 May calling for a non-partisan parliamentary committee to draw up a strategy. The parliamentary committee should be chaired by the Speaker of Parliament and consist of 100 members. In addition to members of all parties represented in parliament, non-partisan experts should also be involved. However, both Bahçeli’s and other political representatives‘ rhetoric still retains its familiar authoritarian tone. This is also evident from Erdoğan’s statement on 22 May, according to which society cannot be ‘united’ on a constitution written by the putschists. (Notably, the current constitution was written after the military coup of 1980 under the direction of the military. The constitution at the time of the founding of the republic was rewritten with a special emphasis on Turkishness). Erdoğan emphasised the need and willingness to draft a new constitution. At the same time, he said that he does not have any problems with the first four articles of the constitution. However, the fundamental problem lies precisely in these first four articles, which ignore and deny the numerous ethnic identities – including Kurds – that are not Turkish. But the rights of Kurds and other ethnic identities – whether social, cultural, or political – must not and cannot be ignored. If we get at the root of the problem, then the PKK and the political struggle of the Kurds are not the cause but the consequence of this anti-democratic and autocratic state doctrine.

The organisation of Kurdish society as a democratic community, along with its willingness to work toward a solution and peace, as well as the steps taken in that direction so far, have been met by state officials with the traditionally authoritarian mindset prevalent in Turkey. The coming weeks and months will reveal whether Turkey is genuinely embarking on a serious path toward democratization and a peaceful resolution, or whether entrenched authoritarian thinking will continue to dictate its practice.

(*) Excerpt from the fifth volume (Turkish title: Kürt Sorunu Ve Demokratik Ulus Çözümü – Kültürel Soykırım Kıskacında Kürtleri Savunmak) of Öcalan’s Manifesto of the Democratic Civilization (2010).

*Devriş Çimen is a Kurdish journalist and politician

Source: Kurdistan Report

(The article appeared in the Kurdistan Report. Due to the current situation, it was published online before the print edition.)