The past and present of Druze and Alawites in Syria - Part One

Communities such as the Kurds, Alawites, Druze, Ismailis, and Christians must organize to protect their existence and secure their rights under a new constitution.

Communities such as the Kurds, Alawites, Druze, Ismailis, and Christians must organize to protect their existence and secure their rights under a new constitution.

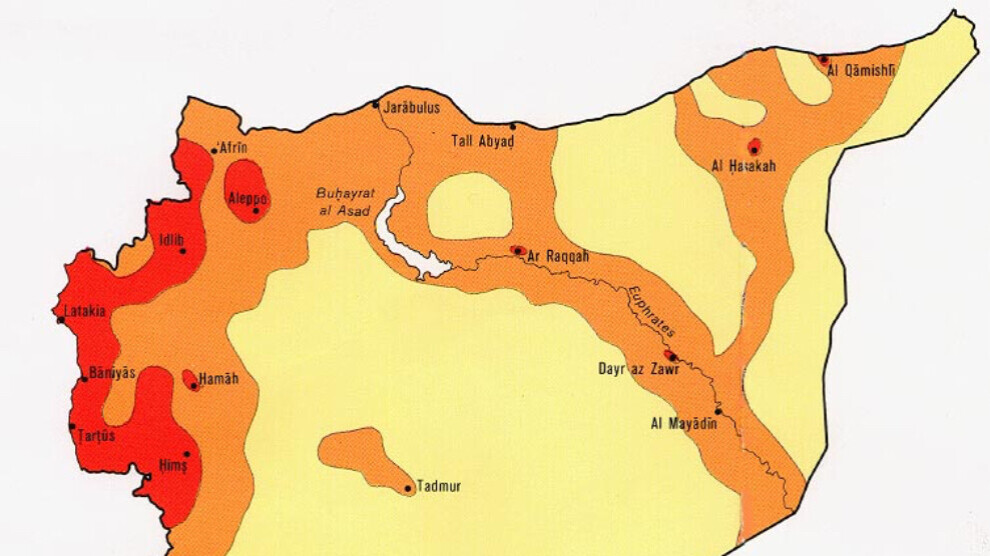

Syria today is believed to be home to nearly twenty different ethnic and religious communities. Alongside large groups such as Arabs, Kurds, Druze, and Alawites, there are also many smaller cultural communities. Groups like the Assyrian-Syriacs, Turkmen, Circassians, Yazidis, Armenians, and Jews are all part of this diverse mosaic, each with their own religious sects and traditions.

The social fabric of Syria includes a Muslim majority, with approximately 85 percent of the population being Sunni Muslims, alongside Alawites (Nusayris), Shia Muslims, Druze, and Ismailis. Christians, who make up about 13 percent of the population, belong to various denominations, including Greek Orthodox, Syriac Orthodox, Armenian Gregorian, and different Catholic communities (Maronites, Syriac Catholics, and Greek Catholics). There is also a small Protestant community among the Christian population. In addition to these, the presence of Yazidi Kurds, Alawite Kurds, Alawite Turkmen, Jews, and to some extent atheists and agnostics, is also noted.

Druze

The majority of the global Druze population lives in Syria, with estimates placing their number between 500,000 and 700,000. They are primarily concentrated in Suwayda and Daraa (Jabal al-Druze), as well as in areas near the Israeli border. Another significant Druze population resides in Lebanon’s mountainous Chouf region (approximately 250,000 to 300,000 people), and in the area around Amman, Jordan (around 25,000 to 30,000 individuals). A small Druze community of fewer than 1,000 people also lives in two villages within Israeli borders and holds Israeli citizenship. Additionally, the Druze diaspora is estimated to number between 100,000 and 150,000. Altogether, the Druze are considered a community of over one million people. These figures are based on estimates and may vary.

The scattered nature of the Druze population is largely the result of artificial borders drawn after the First World War. Historically, they lived in the Levant, a culturally and geographically significant region. The Levant stretches in a wide arc beginning in the Taurus Mountains of Turkey, encompassing parts of present-day Iraq, Syria, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Palestine, and Israel, and extending as far as the Sinai Peninsula and the Gulf of Egypt.

The Levant, whose borders were never clearly defined, later became known as the Province of Damascus. Lebanon, Israel, and Palestine were separated from this province, and later the territory of Palestine was divided, leading to the establishment of the state of Jordan in part of the region. In this way, the territory once encompassed by the Province of Damascus was fragmented and turned into the artificial states that exist today.

Among the major groups in Syria, there is no definitive information regarding the ethnic origin of the Druze. Most of the available information is based on speculation and legend drawn from various sources and does not rely on concrete evidence or verified data. Though not definitive, some sources trace their origins to the Hittites or the Galatians; others suggest Iranian roots, linking them to Persians, Medes (due to similarities in belief systems), or Mazdakites (Mazdakiyya). Some accounts link them to the Phoenicians, while certain Jewish sources claim they were workers from Sidon who settled in the mountains of Lebanon and worked with timber for Solomon’s Temple. There are even narratives suggesting that they are descendants of Christians who remained in the region after the Crusades.

The Druze themselves, however, claim Arab identity. This is also the most widely accepted and supported view. According to this perspective, they are thought to be Arab-origin groups who intermingled with the Arameans in Yemen and later migrated to the mountains of Lebanon due to a catastrophic flood. With the spread of Islam, they converted and settled in these mountainous regions, which they then made their homeland.

The Druze faith traces its origins to the Seven Imams branch of the Shia Fatimid Caliphate in Egypt. The Shia sect is divided into two main branches: Anatolian Shiism recognizes the Twelve Imams as rightful, while the Fatimids considered only Seven Imams to be legitimate. This difference represents a fundamental split between the two main branches of Shia Islam.

The Fatimid Caliphate (909–1171) has a rather complex history in terms of its foundation. Its initial roots were established in Tunisia, but the state's territory would eventually expand across a vast region, including Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria, Libya, Egypt, Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and even Mediterranean islands such as Sicily, Malta, Sardinia, and Corsica. The Fatimid Caliphate was the first Shia state established within the Sunni-dominated Abbasid Empire.

As internal uprisings and unrest began to threaten the caliphate, the Abbasid state, based in Baghdad, sought to intervene in the region of the Maghreb, which was under its influence. Ubaydullah, a follower of the Ismaili branch of Shia Islam, was sent to the Maghreb to suppress the turmoil. Once there, Ubaydullah ended the weakening and independent Aghlabid state and seized control of many territories, eventually founding the Fatimid Caliphate. Claiming descent from Fatimah Zahra, the daughter of the Prophet Muhammad and wife of Ali, Ubaydullah named his new state after her. The Fatimids aimed to establish a Shia alternative to the Abbasid rule, and in doing so, secured a significant place for themselves in the political and sectarian landscape of the Islamic world.

The Fatimid Caliphate had not yet included Egypt within its territory even by the reign of its fourth ruler. At the time, the region was under the control of another power known as the Ikhshidids. In 969, the Fatimid military commander Jawhar captured Egypt from the Ikhshidids and established it as the new center of the Fatimid Caliphate. In what would later become the capital, Cairo, both the al-Qahira Citadel and the al-Azhar Mosque were built. With these developments, the Fatimid state was formally founded in Egypt.

The Druze faith emerged under the rule of al-Hakim, the sixth caliph of the Shia Fatimid Caliphate in Egypt, as a sub-branch of the Ismaili sect. It began as a doctrine spread in Lebanon by Muhammad bin Isma'il ad-Darazi, who declared himself an Imam. This self-proclamation triggered strong public reaction; in 1016, ad-Darazi was accused of heresy, and in 1018 he was executed by order of Caliph al-Hakim. It is believed that the name “Druze” derives from this figure.

The structure of the faith was later reorganized by Hamza bin Ali, vizier to Caliph al-Hakim. Hamza proclaimed al-Hakim as “the ruler in the name of God” and declared himself a prophet. His declarations sparked mass protests in Egypt, which soon evolved into fierce opposition to the caliphate. These revolts were crushed with violence. At the height of this unrest, Caliph al-Hakim mysteriously disappeared in 1021 and is presumed to have died. In the face of ongoing pressure, Hamza withdrew into seclusion. The new caliph, al-Zahir of the Fatimid Caliphate, subjected Druze adherents to persecution. Many were forced to practice their beliefs in secrecy. Hamza and his followers eventually left Egypt and migrated to Lebanon, where they united with the remaining supporters of ad-Darazi.

The Druze are internally divided into two branches known as the Qaysis and the Yemenis. This division also reflects a historical alignment with the Ottoman Empire and the Mamluks. During the Battle of Marj Dabiq in 1516, the Yemenis supported the Ottomans, while the Qaysis sided with the Mamluks. In later periods, the Druze remained a consistently problematic community for Ottoman rule. They are widely known for their warrior spirit and rebellious nature.

They were the first to resist the Ottoman Empire following its conquest of the Egyptian Caliphate, later the French occupation, and most recently the Ba'ath regime. The regions they inhabited often turned into strongholds of resistance. The Druze rarely raise their flag, but when they do, it signals a call to arms. In short, they are regarded as a warrior people.

During the First World War, the Druze were among the first groups to rise up against the Ottomans, alongside Arab forces. After gaining independence from Ottoman control in 1918, they established the State of Suwayda in 1921, and later founded the Emirate of Jabal al-Druze, named after the mountain they lived on. In 1936, the emirate status of the Druze was abolished.

The rebellious nature of the Druze was once again evident when they sparked the first flame of the Syrian revolution in the Druze Mountain under the leadership of Sultan al-Atrash, in opposition to French colonialism. The uprising quickly spread to Damascus and across many parts of Syria. As a result of this revolt, Lebanon was separated from Syria and declared an independent state, leaving a portion of the Druze population within Lebanese borders.

The first uprising that marked the beginning of the Syrian civil war erupted in Daraa, which has historically been a center of rebellion. Although the initial protests were violently suppressed, they quickly spread across the country and ultimately led to the collapse of the regime. The Druze homeland once again managed to preserve its distinctiveness and did not abandon its aspiration for autonomous life.

In the early days of Hafez al-Assad’s rise to power, he received support from the Druze, Ismailis, Alawites, and Kurds. However, his approach toward these communities remained focused on preserving his rule. As these groups did not receive the level of representation or influence they expected, they were largely excluded from meaningful power. The support once extended to the Assad family gradually turned into opposition over time.

After the fall of the Ba'ath regime, the Druze refused to submit to the rule of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and began asserting their demands for autonomy. The Druze regions of Suwayda, Jabal al-Druze, and the areas near the Israeli border remain geographically fragmented, which poses a serious disadvantage. The Druze live in strategic and mountainous areas such as the foothills of the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, as well as in Kuneytra, Daraa, Damascus, and its surroundings. They have deliberately chosen these mountainous regions to preserve their cultural identity and to protect themselves from external threats.

The Druze maintain a socially inward-facing communal structure. They are known for their progressive approach to gender equality and maintain a high level of social parity between men and women. In matters of religion, religious scholars (ulema) play a central and highly influential role. They are perceived more as a religious minority than as an ethnic group. Only those who undergo a long process of religious education and experience can become scholars, and this is strictly regulated by a closed religious elite. In this respect, they share some similarities with the Yazidi community. Their religious beliefs are kept secret, rooted in a long and concealed history of clandestine organization. Who may become a religious scholar is determined solely by the inner circle of the religious elite, whose activities are entirely inward and closed to outsiders.

Since the fall of the Ba'ath regime, the Druze have followed a political line that supports autonomy. They aim to establish self-governance backed by their own defense forces, which has led to ongoing tensions with the administration of HTS. Despite all attempts by Israel, the Druze have maintained their distance from the Israeli state and have never submitted to its authority.

To be continued...