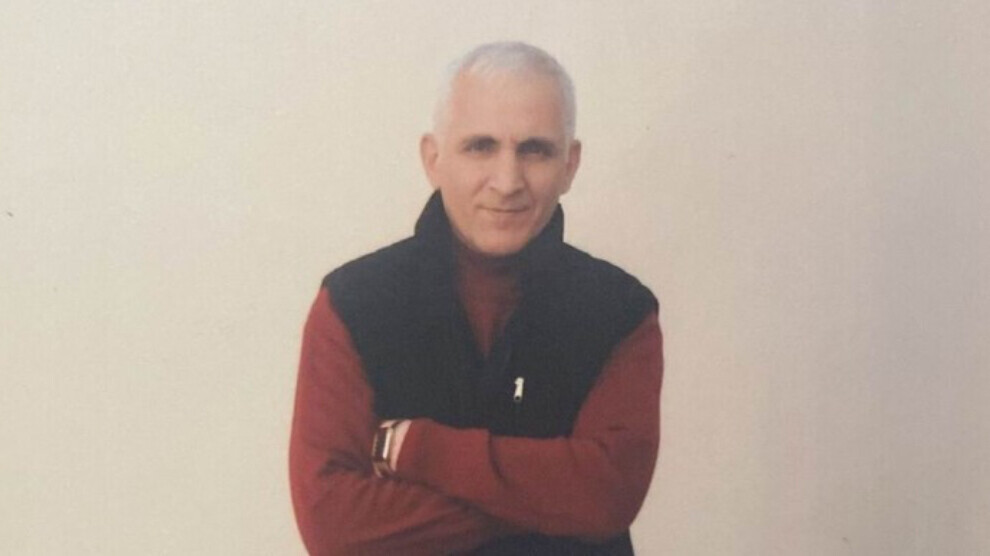

A signature campaign has been initiated for Nevzat Öztürk, a Kurd who has been imprisoned in Turkey for 31 years. His daughter Jiyan, who lives in Cologne, was three years old when her father was arrested in Istanbul in 1992 and sentenced to life imprisonment for "destroying the unity and integrity of Turkey" after 14 days of abuse at a police station. In June this year, Öztürk was supposed to have been released, but his detention was extended by three months. As is usual with political prisoners, release depends on the approval of a control committee, which makes arbitrary decisions with sometimes very absurd justifications. Nevzat Öztürk is accused of "not using electricity sparingly" in prison and "not reading enough books in the prison library".

The Society for Threatened Peoples, together with Öztürk's daughter Jiyan, appeals to the Human Rights Commissioner Luise Amtsberg to campaign for his release. The appeal points out that the situation of political prisoners in Turkey has worsened since the failed military coup on 15 July 2016 and that imprisoned Kurds are being forcibly assimilated: "In Turkish prisons, attempts are being made to assimilate Kurds by forcing them to deny their Kurdish identity and reject their language, culture and history.”

Öztürk has a heart condition and is currently in the Bolu F-Type Prison in western Turkey. The Society for Threatened Peoples reports that the 57-year-old has been transferred again and again: "Visitation and telephone bans are the order of the day. His wife and son, who still live in Turkey, have to travel 1300 kilometres to see him - only to be turned away sometimes. Here, too, state arbitrariness reigns. Will Öztürk actually be released in three months? That is uncertain. We want to campaign for this with you. Sign the appeal now and demand his release!"

Dr Kamal Sido, the Society for Threatened Peoples’ Middle East expert, says: "In Turkish prisons or police custody, up to 83 people are said to have died under suspicious circumstances in 2022. Reports of torture in Turkey's overcrowded prisons are also mounting. Worst of all, however, is the arbitrary practice of not releasing prisoners even after they have served their sentences of often more than 30 years."

In recent months, many prisoners have been released who, like Nevzat Öztürk, were sentenced to life imprisonment in the early 1990s in the now abolished state security courts. However, about 200 political prisoners are not released even after serving their regular sentence. A committee decides on release at its own discretion. Without the approval of this committee, release can always be postponed for three or six months. One of the common questions asked by the committee for its social prognosis is: "In your opinion, is the PKK a terrorist organisation?"