In November 2015, the destruction of Sur began with the declaration of a curfew. In the old town of Amed (tr. Diyarbakır), which has a five-thousand-year history and is protected by UNESCO, self-administration had been declared shortly before. For more than three months, the people in the neighbourhood resisted a barbaric plan of attack by the Turkish state. The destruction continues to this day, and tens of thousands of people have been dispossessed and displaced.

Hakan Arslan was one of many people who opposed the military siege of Sur as the Civil Defence Units (YPS, Yekîneyên Parastina Sivîl). In January 2016, he died at the age of 23. His friends buried him in the Hasirli neighbourhood, between the Armenian Catholic Church and the small mosque. Exactly five years later, during restoration work at the same site, workers came across human bones wrapped in a cloth. The assumption was quickly made that these could be the mortal remains of Hakan Arslan.

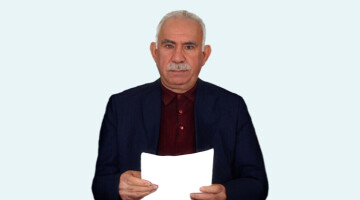

Hakan Arslan was a native of Erzurum. The Kurdish youngster’s parents had been told shortly after his death where the body had been buried. After the military siege of Sur ended, the family turned to the Diyarbakır General Prosecutor's Office and the Turkish Ministry of the Interior. They wanted to have their son's body recovered so that he could be buried according to Islamic tradition. The family wanted to have a place of mourning and remembrance for themselves, but they were unsuccessful. Not one of the dozens of applications they made was granted. In most cases, there was not even a reaction to the request.

After the bones were found in February last year, Hakan Arslan's parents again turned to the authorities in Amed. They provided DNA samples, and the Institute of Forensic Medicine in Istanbul compared all the profiles. From November 2021, the result was clear, and the dead man from Sur was 95 per cent likely to be Hakan Arslan. Nevertheless, the family had to wait more than nine months for the body to be handed over - a well-tried tactic of psychological warfare by the Turkish state. Last week, the long-awaited call came and the Diyarbakır prosecutor’s office summoned Ali Rıza Arslan to the office to hand over his son's bones. The man had been waiting there since Thursday, but the handover did not take place until Monday, when his son's bones were handed over to him in a bag. Now Hakan Arslan is to be buried again in his birthplace, Erzurum.