The Turkish state has long pursued an expansionist policy in the Middle East, driven by its ambition to become a hegemonic power in the region. The regional balance, however, shifted dramatically after Hamas launched an attack against Israel on October 7, 2023, followed by Israel’s immediate response. This new regional dynamic brought Turkey’s hegemonic plans into conflict with the strategies of international powers in the Middle East. Viewing this development as a threat to Turkey’s future, the Turkish state apparatus, led by Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) leader Devlet Bahçeli, took action. In October, a call was made to Abdullah Öcalan, urging him to dissolve the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and benefit from the so-called "right to hope."

However, the process has not continued with the momentum described by Devlet Bahçeli at the outset. Especially after the 12th Congress of the PKK, the state and government have begun to slow down the process, stretching it over time.

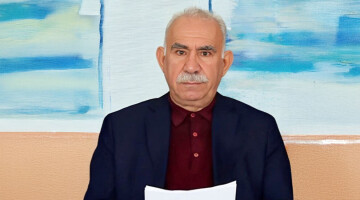

Journalist Ferda Çetin spoke to ANF about the unfulfilled steps in the process, the international and regional context, the risks of putting the process on hold, the construction of a democratic society, the role of democratic communes, and the political perspective of Abdullah Öcalan.

We publish the first part of the in-depth interview below:

The ongoing discussions on the process and dialogue in Turkey began with the call made by Devlet Bahçeli in October. Despite the unexpected nature of this call and the rapid steps that followed, we now observe that the state has slowed down the process, even resorting to stalling. The state or government entered the process quickly, but why has it started to slow things down? What is the reason behind this?

It was not only Devlet Bahçeli’s statement; very rapid and significant changes also took place both in Turkey and the Middle East. Over the past 20 years, especially since Ahmet Davutoğlu’s term as Minister of Foreign Affairs, Turkish foreign policy has pursued an expansionist agenda under the concept of "strategic depth." Serious efforts were made to implement this policy in practice. Turkey aimed to regain power and become an influential actor in the Middle East, the Caucasus, and regions once dominated by the Ottoman Empire. They not only theorized this approach but also engaged in concrete interventions. The Exclusive Economic Zone Agreement signed in Libya in 2019 can be cited as an example. With this agreement, the Turkish state dared to assert dominance over almost the entire Mediterranean. Turkey was carrying out this policy in the Caucasus, the Balkans, and many other regions. The bipolar and multi-actor global order allowed for such maneuvering. Turkey sometimes aligned itself with Russia, sometimes with the European Union or the United States, and at other times positioned itself against these powers. This balancing act continued for 20 years. On the other hand, the United States (US), the United Kingdom (UK), and Europe also had their own agendas and pursued their own policies. From the overthrow of Saddam Hussein to the fall of Hosni Mubarak and Muammar Gaddafi, the attempted change of regime in Syria, and the near elimination of Hamas and Hezbollah… All of these developments created circumstances that undermined Turkey’s ambition to play an active and influential role in the Middle East. This is one of the reasons. In other words, an international context emerged that forced the Turkish state and the AKP (Justice and Development Party) government to adopt a more realistic approach.

Are you referring to the situation Devlet Bahçeli described as "the risks and dangers awaiting Turkey"?

Yes, but how much risk and danger are we talking about? When you pursue an expansionist policy or occupy other countries and territories, and if there are other power centers with claims in those areas, a confrontation or even a retaliation becomes inevitable. This can be clearly observed in the case of Syria. For a long time, Turkey maintained its pressure on the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, which was formed by the Kurds together with other communities in Syria, under the pretext of "security" and "border security," claiming that it would not entrust its border security to Europe or the United States and would take matters into its own hands if necessary. The policies of "we might strike overnight," the daily drone bombings of the region, and even the audacity of Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan declaring that "all infrastructure and superstructure institutions will be targeted" were all aimed at establishing full control and domination over Syria.

The potential change of the Bashar al-Assad regime represents a radical shift against Turkey’s expansionist policies. Sheltering behind the excuse of border security, Turkey has now, or rather since the shift in the Syrian regime, found itself bordering Israel. Israel is present in Syrian territory, controlling military operations and the military order there. Just two and a half years ago, Turkey viewed the Kurds as a threat. Now, Turkey urgently needs a new neighbor, one like the Kurds or the Autonomous Administration established by the Kurds, a neighbor that does not create problems and does not pursue expansionist or occupation policies. This situation has emerged quite suddenly.

Turkey is now calculating how it will get along with its new neighbors. Even though it supports ISIS, the Syrian National Army (SNA), or Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), it is still a neighbor of Israel. This is not a prediction or a future projection; this is the current reality. Israel’s new expansionist policy in Syria and the Middle East, which it does not carry out alone but in partnership with the United States and the United Kingdom, has completely overturned Turkey's strategy of "strategic depth" and its ambitions to reclaim former Ottoman spheres of influence. In this period, Turkey needs neighbors and peoples in the Middle East with whom it can get on without conflict. The two countries that need this the most are Turkey and Iran. These two countries, with their internal problems, have now become focal points of international plans and projects. Therefore, Bahçeli's statement can be seen as a new move or political approach driven by realism and by the pressure of these new neighbors and new circumstances. It did not arise out of nowhere.

Bahçeli made that call in October based on a realist policy, initiating the process. However, it is clear that the process has not continued as it started. What has changed? Why did the government or the state adopt a slowing or stalling tactic? Why is it not proceeding as it initially did?

Turkey did not expect such a rapid transformation in Syria. The Turkish state and the AKP government actually feared that the policy developed by the United States, the United Kingdom, and Israel would eventually exclude Turkey altogether. This was the source of their fear. As a new Syria was taking shape, Turkey believed that once the SNA, HTS, and other factions it previously supported were fully dismantled, Turkey itself would also be eliminated from the equation and would be confronted with major chaos and uncertainty. In order to prevent this outcome, cooperating with the Kurds or entering into a new phase of relations that went beyond previous hostilities with the Kurds appeared to be a smarter option for Turkey. What pushed Turkey in this direction was, in fact, its own failed prediction. However, those implementing this new plan also incorporated the SNA and Turkey into their project for Syria. As a result, Bahçeli, Tayyip Erdoğan, and the Turkish state came to understand from the unfolding practical developments that the situation was not as dangerous as they had initially feared, that the process was advancing gradually, and that Turkey was not being entirely excluded. Seeing this, they adopted a more cautious and slow-paced approach to the process.

However, tensions between Turkey and Israel are rising on the ground. Israel has bombed areas where Turkey intended to establish military bases, and mutual threats are being exchanged, sometimes over Hamas, sometimes over Syria. What does this signify?

Turkey has pursued this policy for years. Especially after the Kurds established the Autonomous Administration, Turkey adopted an aggressive policy targeting the Kurds and attempting to prevent them from becoming an equal partner in Syria. This approach continues in some form today. However, after the fall of the Bashar al-Assad regime and the withdrawal of Iran and Russia from Syria, Turkey found itself facing the United States, the United Kingdom, and Israel directly. Yet, due to Iran’s and the Assad regime's inability to protect themselves or establish full authority, Turkey managed to become a power in Syria, both militarily and politically, positioning itself as one of the main actors. Following Assad’s fall, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Israel became actively involved, initiating discussions and planning for Syria’s future. One of the key points they emphasized was that no independent military forces would be allowed to form in Syria without their approval, meaning groups like HTS or other foreign forces could not establish their own armed structures unless sanctioned by these powers. This is the background behind Israel’s bombings and the obstructive policy you mentioned. At this point, Turkey no longer insists on its previous hardline stance. Unlike before, when it responded with open challenges or provocative countermeasures, it now seeks to pursue the most flexible and conciliatory policies possible, avoiding direct confrontation with Israel. Turkey’s sole insistence, which it continues to press on the countries planning Syria’s reconstruction, is that the Kurds must not be granted any official status or become equal stakeholders in the new Damascus administration. This remains the basis of its negotiations. Turkey is no longer in a position to control or design the new Syrian administration. It does not possess the power to do so.

When this process began, Devlet Bahçeli used terms such as "Kurdish-Turkish alliance," "renewed paradigm," and "Kurdish-Turkish brotherhood." It was stated that “Turkey will prepare for the new century on the foundation of Kurdish-Turkish brotherhood." Yet, based on your assessments, it seems that Turkish attacks against Kurdish gains continue. Specifically in the Syrian context, does Turkey still maintain an anti-Kurdish position?

The discussions on this resolution process did not emerge from the efforts of Turkey’s internal dynamics, civil society, political circles, or societal struggles. This much can be clearly stated. The government and Bahçeli took positions based on the results imposed by the current conjuncture and rational conditions. In other words, they recognized that maintaining previous relations with the Kurds, marked by war, conflict, and tension, would bring no benefit to Turkey. In the context of the new order, the redistribution and reorganization of the Middle East, the ongoing conflict and tension would only harm Turkey. They saw and understood that the Kurds had achieved a strong position, that they were becoming an actor in this new process and securing a place in the emerging new Middle East. For this reason, they felt the need to initiate such a process. This did not develop from a grassroots movement, societal pressure, or a genuine environment of peace, brotherhood, and coexistence.

Even when viewed from a rational perspective, why do the Kurdish gains in Syria disturb the Turkish state?

Peace talks or negotiation conditions between conflicting sides or states do not arise the moment both parties desire peace and brotherhood. They usually emerge when the parties lose their position to achieve victory or to defeat the other side. This is the core of the problem. The atmosphere of democratization and peace in Turkey did not emerge as a result of internal dynamics or demands of the peoples within Turkey. In reality, Turkey has not abandoned its former policy. Instead, it made a shift in this way: the government came to believe that constant war, conflict, and confrontation with the Kurds were not in Turkey's best interests. That is why this path was taken. As a result, Turkey finds itself stuck in a position that continuously hesitates and oscillates between old and new approaches when it comes to discussions of peace, brotherhood, or democracy. The Turkish state or the AKP government and the PKK did not come together because they reached an agreement on peace and democracy. Rather, they reached a shared conclusion that conflict and war were deepening the problems, harming both sides, and that negotiation would be the correct approach. A mutual consensus was formed on this point. Bahçeli's call and the response from Abdullah Öcalan should be interpreted in this way. Only after such a process can democracy or a democratic ground begin to develop. Therefore, it is not accurate to confuse the two. The foundation for peace and democracy is something that must be built and advanced through struggle. It is not a ground that will be established by the promises of Turkey, Devlet Bahçeli, or Tayyip Erdoğan. This is a process that must evolve and be constructed step by step.

What risks does this slowing or stalling carry for the process? Is this a sustainable situation?

The call made by Devlet Bahçeli and the response given by Öcalan represent extremely radical steps. Statements such as "let him come and speak in parliament" and Öcalan's declaration that "I will call on the PKK to dissolve itself and hold a congress" are not decisions that can be made casually or expressed at any moment. They are irreversible steps. Although their consequences have not yet fully manifested, very significant and radical decisions have already been taken. If developments do not proceed in accordance with these steps, or if a parallel course is not followed, then everything will become meaningless. The attempt to build Kurdish-Turkish brotherhood, to reorganize democracy in Turkey, to review and correct past deficiencies and mistakes, all these objectives will lose their relevance.

The greatest risk is the recurrence of policies that govern and manipulate society through conflict, tension, defensive warfare, and continuous hostility. Such a scenario would benefit neither Turkey, nor the Kurds, or other societies in the Middle East. This situation can be explained in this way. Something has happened that was not seen before, within Kurdish society and on the Turkish side. The vast majority of political parties, almost 80 to 90 percent, issued statements supporting this process. Such a consensus does not emerge easily. The Kurds also do not always approach such processes in this way. Not only the PKK, but also the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), the Gorran Movement, the parties and organizations in Northern (Bakur) Kurdistan, and Kurdish institutions as a whole have described this process as promising. However, they emphasized that it must advance and that reciprocal steps must be taken. Since the PKK congress was held, a period of stagnation has followed. Öcalan's call and the PKK’s congress decisions clearly demonstrated the Kurdish side's intention and practical willingness to advance the process. The disruption is not occurring on both sides. The slowdown is coming from the Turkish state and the AKP.

Could this situation be described as an abuse?

It could be called an abuse, a stalling tactic, or as commonly said, an attempt to sweep things under the rug. No matter how it is defined, this reflects a policy that moves slowly and lacks seriousness.

Beyond the unfulfilled steps and stalling, attacks on the guerrilla forces continue. Erdoğan and his circle still repeat the familiar rhetoric of "our struggle will continue until the last terrorist is eliminated." The term "terror-free Turkey" is also frequently used when addressing this process. How do you interpret this situation?

There is a passive state that cannot even name what we are discussing, one that fears even acknowledging it. However, this fear does not stem from opposition forces within Turkey. There is no such pressure on the AKP government. No force outside of Tayyip Erdoğan, Devlet Bahçeli, the ministers, or the National Security Council is pushing this process forward. Although there is often talk of a deep state in Turkey, the AKP fully controls all these elements. There is no such fear in that sense.

Yet, the AKP and MHP government is now the one creating obstacles in taking the simple, necessary, and proper steps it should take. One of these steps was to ensure that Öcalan would be able to work under favorable conditions. This is essential so that he can establish dialogue and contact with the organization, the guerrillas, and those who would lay down arms. In parallel with this, the Turkish army should also have declared or practically observed a ceasefire in response to the guerrillas’ ceasefire decision. It was not even necessary to announce this to the press. The attacks should have been halted in practice. This was not done. Instead, they continually speak of political fears, claiming they cannot take certain steps openly but will do so gradually. Yet, when it comes to attacks against the guerrillas or operations targeting Southern (Başûr) Kurdistan, such hesitation does not exist. When Turkish warplanes do not bomb, there are no protests or uprisings in Turkey where certain forces cry out, "Why are you not bombing?" This shows that the government or those who supposedly want to advance the process do not treat this matter with the seriousness it requires, nor do they see it as a significant obstacle. However, for the Kurdish side, for the guerrillas, this is a very serious issue. It is perceived and interpreted as a sign that the state, the Turkish troops, and the Turkish army do not recognize the process initiated by the government and do not intend to implement it. As a result, it generates greater caution, leads to a more careful observation of the process, creates distrust, and raises doubts. This is the greatest danger.

Along with these attacks, the government continues its attacks in the political sphere as well. Criticisms have also come from the Kurdish Freedom Movement in this regard, stating that "the government wants to divide the opposition." Operations against municipalities ruled by the Republican People’s Party (CHP) continue. Although the CHP’s stance during this process has been positive, there is criticism that these attacks aim to push the CHP out of the process. How do you assess this? What is the government’s goal and objective here?

Devlet Bahçeli’s remark "let him come and speak in parliament," and the discussion of the PKK dissolving itself and abandoning armed struggle rest on a single, unquestioned condition. That condition is the opening of the political sphere in place of armed struggle. The guerrillas are not in the mountains merely as war enthusiasts, fighters, or individuals who simply use weapons. The guerrilla is also a political force. It represents and demands the rights, legal status, and political aspirations of the Kurdish people, using arms as a means to achieve these goals. If weapons are to be set aside, there must be a legal and legitimate foundation for this. A democratic environment must be established in Turkey. Without such a foundation, statements about "brotherhood, unity, solidarity, and historical friendly relations with the Kurds" carry little meaning.

Even now, while pressure and violence may not be as widespread in some parts of Turkey, Kurds remain under heavy repression. Prisoners who have served their sentences are not released. At the same time, political parties face pressure, government-appointed trustees take over municipalities, journalists are arrested, and even minor criticisms or reactions result in people being detained and imprisoned. These conditions do not create a basis for peace and brotherhood; on the contrary, they create the opposite. Repression, state terror, imprisonment, trials, detentions, and arrests continue in western Turkey, while speaking of friendship, brotherhood, or good relations with the Kurds is unrealistic. This contradicts both the nature of things and the system that is supposedly being built. Such a situation can only be possible if democracy advances. Freedom of thought and expression, freedom of organization, full protection and respect for the right to vote and be elected, the complete removal of the trustee system, and the abolition of decree-laws must all be ensured. As long as these issues remain, brotherhood, peace, democracy, or good relations will not be possible.