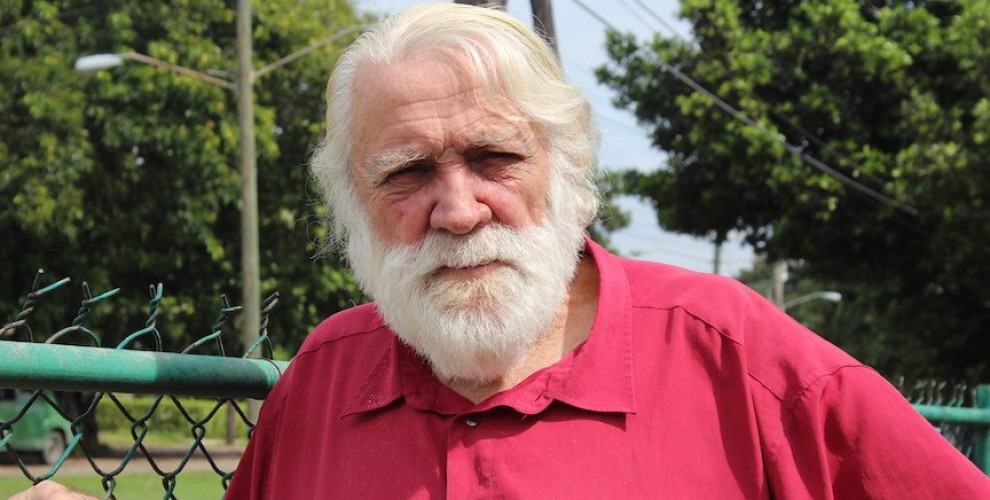

Communist writer Daniel Chavarria dies in Havana

Daniel Chavarria, great writer and communist, has died on Friday in his beloved Havana. He was born in Uruguay in 1933 but his incredibly adventurous and political life brought him to many shores.

Daniel Chavarria, great writer and communist, has died on Friday in his beloved Havana. He was born in Uruguay in 1933 but his incredibly adventurous and political life brought him to many shores.

Daniel Chavarria, great writer and communist, has died on Friday in his beloved Havana. He was born in Uruguay in 1933 but his incredibly adventurous and political life brought him to many shores.

A great internationalist, he sided with Kurds, who he loved and admired for their stubbornness that, he said “remind me of myself”. Every time I went visiting him in his place here in Havana, the first thing he would ask was, “How are the Kurds?”. He had adopted the whole people as it was a son or, rather, a daughter. Our time together was always rich in conversation and new ideas. Daniel’s wife, Hilda, was always with him, a real rock and important presence not only emotionally but creatively as well. We would make “çay” (“Have you brought me a bit of Kurdish çay?” he would ask) and drink it talking about Kurds and their language (Daniel spoke many languages and was fascinated by the power or words), the many struggles Daniel had waged and lived through.

He got very intrigued by all the story told by Edward Snowden and asked me to get some books about him and security because, he said, he had a novel in mind about the world we live in and the amount of abuse and violation we are subjected to.

Daniel had arrived in Cuba “running away from police”. Indeed he landed in Havana on a plane he had hijacked in Colombia were he was sought for helping the Communist party there.

Among other prizes, he has won the Literature Cuban Nacional Prize and its equivalent in Uruguay, as well as the Casa de las Americas Prize and the Hammet (United States) for the best detective novel of 2014. And Cuba has nominated him National Literature Prize in 2016, with a great tribute at the Havana Book Fair.

We publish the last interview we realised with him.

How was your encounter with literature, before as a reader and later as a writer?

I became an assiduous reader when I was 9. It was a Sunday and my mother had punished me by forbidding me to go to the pictures, which meant I missed watching a Bud Abbot and Lou Costello film. They were bad Hollywood comics but very popular among us kids in my borough in Montevideo. An uncle of mine, who was living in our house and was a student of law with philosophical and artistic interests, pushed me to read the first ten pages of Huckleberry Finn, to cheer me up. He ensured me I was not going to be able to drop the book. And indeed it was what happened. Since that time I think I haven't spent a single day of my childhood and youth without reading some fiction.

My conversion into a writer was something unusual. I wanted to be one for my first 40 years of life. I started 14 novels and couldn't finish a single one. When I had given up writing novels, suddenly and only to prove I could write something better than a big novel published in Cuba and very much praised by the press, I wrote a spy novel [Joy] that ended up being a world bestseller in the socialist world. Literally overnight this little work transformed me into a successful writer and I didn't want to do anything else but writing in my life.

How do you chose what is of interest for your literature?

In general, I believe that what interests me is what I can't understand of the behavior of someone. And by trying to understand this behavior I end up building up a literary plot. I give you an example. When I was living on the fourth floor of a house with a view to the sea, every night, around sunset, I used to see a young man, 25 years old, who instead of throwing his hook from the coast, he tied one end of the cord to the coast and with the other end in his left hand, he swam on his right side, without wetting his head, for three times the distance the other hooks had been thrown from the coast by the other fishermen. Now, the boy of course was the object of comments about his madness or ignorance. Nobody right in his head would swim at this time in deep waters, precisely when sharks are approaching the coast looking for something to eat. In reality the sharks never did that, and this was a false danger, yet among the fishermen tales and legends there was this one too and many believed it. I believed it too, and ended up writing a novel about a psychopath who to enjoy sex needed to excite himself with danger. Had he not done so, he would have been impotent. The novel was called Primero muerto que impotente (Better dead than powerless). I never published it with this title and in the original form, though. I ended up changing it and transforming it in a different thing. But the origin of it was my attempt to explain in a logic way the absurdity of fishing risking your own life.

You describe yourself as an Uruguayan citizen and Cuban writer. How do you describe the idea of “identity” and how you represent it in your characters.

Cleary it exists an idea of “national identity” as a group of features of the peoples, considered as homogenous human collectives, even though they then united themselves as nations. I have lived and worked for many years in many countries of Nuestra America (Our America) from whose inhabitants I have acquired some “local colour” that can be appreciated in my vocabulary, culinary tastes and other things. I not only feel Uruguayan and Cuban, I also feel Argentinian, Chilean, Peruvian, Brasilean, Bolivian, Venezuelan, Colombian, and more. I feel and I am Latin-American.

Why did you come to Cuba? How was the literary scene when you got there?

I came to Cuba to run away from police. I was then working with a Colombian guerrilla movement. It was directed by a catholic bishop of the Liberation Theology. Some informer told the police where I was to be found but luckily I was warned by friends of the imminent danger and, as I saw no other way to run away, I hijacked a small plane and flew to Cuba, that since January 1959 had become the lighthouse of Latin-American liberation. I had previous links with Cuba, since my times as a militant of the Uruguayan Communist Party.

As to the literary scene at that time, I met two of my personal inspirational figures still living: Alejo Carpentier and Nicolás Guillén. I had no reference of other leading literary figures of the time. Of course there was then, going back in time, one of the biggest poet of our language, who was also a brilliant essayist and a paradigmatic patriot and political visionary: Cuban national hero and Apostle, José Martí.

How would you summarize your work to date?

I begun with a political adventures novel (NPA), translation of what the soviets called “detective political novel”, which differs from the crime novels of the capitalist world because it based on real facts. In it, fiction occupies the space you like, but in a way it is conditional to the respect for inviolable historical frames/context. It is a genre of great formative/educational value, especially for young people. My first novel published in Cuba, Joy, belongs to this genre. I also have a notion for historical novels, biographies and what I call picaresca cubana (Cuban picaresque). These four trends however are mutually contaminated. In the NPA you can find the great aesthetic and stylistic ambition of the historical novel, while in the historical plots you'll always find the crime story suspense or the strong erotism of the picaresca cubana. And in the biographical genre I get much closer to an emblematic fiction than to a documentary tale.

Do you make use of the “real meravilloso”, the “real wonder” ?

Although Carpentier and Hundred Years of Solitude represent in my opinion one of the highest fiction of the post-Cervantes Spanish language, my novels belong to a trend I have baptized “realism of the credible exceptional”.

Almost always my protagonists are exceptional beings and act an unusual environments and very complex plots. However I imposed on myself the prohibition/forbid myself to violating - of never violating the possible and believable. I never resorted to some very frequent scenes in current literature and cinema, where the soul of a dead person, for example, observes what is happening around his coffin during the wake.

Of course, I don't criticize these techniques, and in some cases they have been wonderfully employed; from Homero and the tragic Greeks to Dante and Shakespeare, just to name perhaps the highest examples.

In the Cuban picaresque many of the protagonists are extremely contradictories in their ethical values and are on the border or live in the margins. Why do you describe them in such a way ?

I believe in the goodness of socialism and in my novels I defend that. But I am very careful not to fall into euphemism, a vice both unfortunate and very counterproductive. When it comes to deal with Cuban realities, I always remember that despite the patronising sleepless nights of the Revolution to protect citizens, some have run with very bad luck. When you are born in a family burdened with the inevitable heritage of underdevelopment, with violence as sexism, selfish opportunism etc, or when a child had no luck at school and his teachers were immoral and opportunistic, ill treating children and demanding presents and gifts… this has unfortunately occurred and still occurs in Cuba, you have to expose this. Literature enrich itself with contrasts, with opposites, therefore I am used to appeal to some innate virtues of the human being, that despite his inherited vices and the hate for the Revolution, maintain a sense of justice, great loyalty to friends, and are able to risk their skin to defend a foreign cause. This was my intention when I created Bini, the protagonist of “El rojo en la pluma de loro”: she is a young antisocial girl, who doesn't study nor work and dreams with going to the US. Once adult she prostitutes herself and she has been in prison a few times for different crimes. Yet she is able to collaborate with total selfishness to the capture of a torturer who had harmed one of her client when he was a political prisoner in Argentine.

The crime and spy genre allows room for an almost journalistic investigation, in the sense of a description of the political and social context. In this sense could the writer be a sort of Emile Zola and re-write his classic article J'accuse ?

Indeed, now that you ask me this, I realize I have used this resource more than once. In particular I remember two short stories:

Por culpa de un jodido bicho español (All because of a damn Spanish kid), where I describe a mercenary from El Salvador recruited by Posada Carriles, who in 1997 planted a number of bombs in different hotels of Havana; and El ángulo recto de 70 grados (the rect 70 degrees angle) , about one of our Five Heroes, and his use of self-suggestion in order to resist without tembling, the perverse detention in a hole where prisoners get mad as they are prevented from assuming any position allowing them to get some rest. Both stories are a J'accuse against systematic torture employed in the US, the self-proclaimed defenders of democracy and human rights.

Your work and indeed you as a person, have always kept a positive relation with the Cuban Revolution: did you have to pay a price for being consistent and honest? For example in terms of publishing or the distribution of your work.

Yes, definitively so. I am sure that if I were to write a novel today, and I am 83, saying that indeed Cuba has deluded me after 45 years living here and thinking that this was the sacred land of socialism, I will become a super star! My books will instantly being translated in various languages and sold around the world.

Nevertheless you have been awarded important prizes, included in the US. How important are literary prizes for you ?

I have to admit that they do satisfy my vanity, to a certain extent. For a writer of the Third World, to win 50 thousand dollars out of the blue, well it's not a small thing. I am not saying money it's all, on the contrary, but it does help to calm down!

Your last book is a biography of Raúl Sendic, the Uruguayan guerrilla leader.

I admire Syndic for his character and boldness; for his huge knowledge, for his endless readings, for his analytical skill of the social phenomena and also because he pointed out to us how bad positioned we, the communists and socialists in Uruguay, were with respect to the class struggle axis. However some of his mistakes as a mass leader, were for me impossible to defend and yet I finally decided to praise him as the biggest “Quijote” of Uruguay.