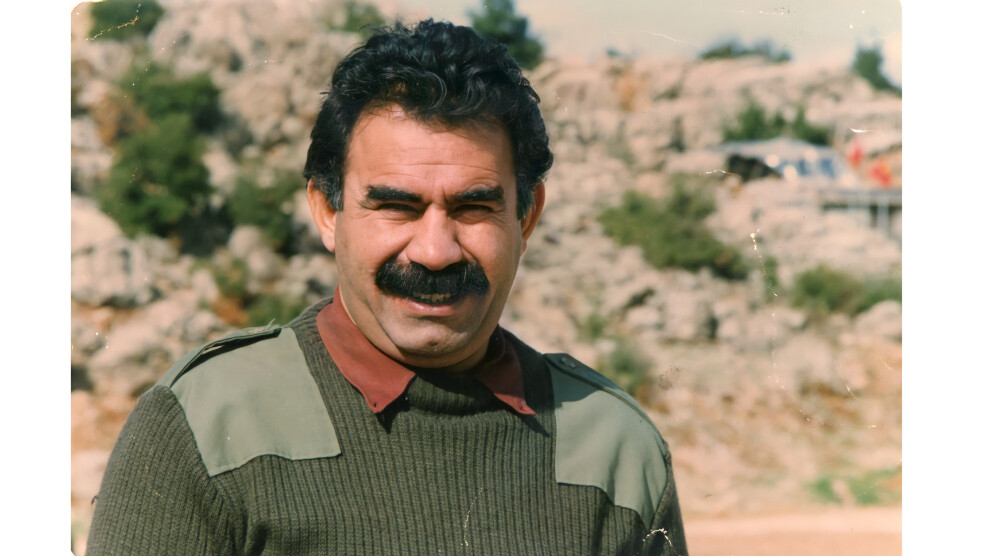

This February 15 marks the 25th anniversary of the kidnapping of Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) leader Abdullah Öcalan in Kenya, and his transfer to Turkey where he was confined on Imrali, a small island in the Sea of Marmara. He will be 75 years old on April 4.

For ten years, Öcalan was the only prisoner in Imrali's high-security prison, guarded by a thousand Turkish soldiers. As noted in the foreword to the book Freedom Will Prevail, a short biography of Öcalan published in 2021, "the island of Imrali thus became a precursor to the infamous Guantánamo detention center.”

In the first decade of the century, Öcalan wrote texts and books on history, philosophy, and social sciences that revolutionized Kurdish politics, and coined the proposal of "democratic confederalism" as a non-state political system.

Starting from July 2011, he was not allowed contact with his lawyers again until May 2019, following a massive hunger strike demanding an end to his solitary confinement.

Between January 2013 and April 2015 there were talks between Öcalan, the PKK and the Turkish state to reach an agreement to resolve the Kurdish issue and bring about a negotiated solution to the long-running conflict. But in 2015 they broke down, and Turkey unleashed a new wave of violence against the Kurdish people and Öcalan was again completely cut off.

In the midst of the isolation of their leader, the Kurdish people started a hunger strike on November 8, 2018, initiated by HDP party MP Leyla Güven, who was imprisoned in violation of her parliamentary immunity and a court ruling. Approximately 250 political prisoners joined Güven in an indefinite hunger strike demanding an end to Öcalan's solitary confinement. Up to 8,000 people around the world participated in various ways in the hunger strike, including political prisoners across Turkey and politicians, academics and activists in Europe, the UK, America and the Middle East.

In the face of the mass hunger strike, in January 2019, he was allowed a brief visit with his brother Mehmet, marking the first contact of any kind with Öcalan since September 2016, and May saw the first visit by his lawyers since 2011. On May 22, 2019, Öcalan issued a statement calling for an end to the mass hunger strike against his solitary confinement.

Punishing an entire people

When we ask ourselves about the reasons that lead a state like the Turkish one to impose such a cruel measure of isolation and noncommunication, the reflection leads us to our own history as Latin Americans, to try to find some answer.

History takes us back to the dismemberment of the leaders of the greatest anti-colonial revolts, Tupac Amaru and Tupac Katari, by the Spaniards. The aim was not only to punish the rebels who rose up in 1780, but all the Andean peoples.

On November 14, 1871, Tupac Katari was quartered by four horses in his hometown, Peñas, in the presence of many indigenous people. As a punishment, his head was placed in the Main Square of La Paz, the right hand was sent to Ayo Ayo and Sica Sica, the left hand to Achacachi, the right leg to Chulumani and the left to Caquiaviri. The trunk was burned until it turned to ashes, which were thrown into the wind so that no traces of Tupac Katari would remain, so that the indigenous would no longer rebel against the oppressor.

I believe that Öcalan's abduction and isolation pursue the same objective. To intimidate the Kurdish people and prevent a peace agreement from being reached. As noted in his political biography, "Abdullah Öcalan's imprisonment has become the symbol of a Middle East drowning in dark times, and his release has become the symbol of freedom."

In general, the cruelty of the oppressors is motivated by their fear of those who resist them with dignity. They fear the peoples they represent, their will to persist in the struggle for collective freedom, and in particular, they distrust the women from below who are the main bearers of collective memory and hope. On this point, extensively developed in Öcalan's writings, we must remember that patriarchy is being harshly challenged by women all over the world, and that it reacts violently precisely because of the fright and astonishment provoked by their emancipation process.

Since his isolation in Imrali prison, Öcalan has become an outstanding political and intellectual personality in the world who was able, in the second half of the 1990s, to "liberate" himself from inherited dogmatic thinking (in reference to Marxism-Leninism). In dozens of books, Öcalan made a profound self-criticism of dogmatic thinking and opened his mind to new ideas, among which democratic confederalism stands out. His critique of patriarchy gave impetus to Kurdish feminist thought, Jineology, developed by the women of the movement.

As Öcalan's biography highlights, his confinement and the persistence of the Kurdish people contributed to spreading the characteristics of a movement little known twenty-five years ago, and which now represents, together with Zapatismo, the greatest hope for the peoples of the world. Hope anchored in an ethic different from that of the oppressors and, also, different from that of the revolutionaries who fight symmetrically against capitalism. As this sentence from Freedom Will Prevail states, "They have not treated their captivity at the hands of a series of occupying powers as a source of resentment, but, on the contrary, they have used it to demonstrate that the only way out of the existing quagmire is the solidarity and freedom of women and peoples; the freedom of one is simultaneously the freedom of the other."

Source: Desinformemonos

Who is Raúl Zibechi?

Born in 1952, Raúl Zibechi is Uruguayan. Journalist, commentator and writer, he is in charge of the international section of the well-known weekly Brecha, published in Montevideo. He is the author of several books on social movements. In 2022 his book "Mundos otros y pueblos en movimiento" was published. Between 1969 and 1973 he was an activist of the Frente Estudiantil Revolucionario (FER), a student group linked to the Tupamaros National Liberation Movement. During the military dictatorship that began in 1973, he was an activist in the resistance against the regime until 1975. In 1976 he moved to Buenos Aires (Argentina), where he went into exile following the military coup d'état. In 1976 he settled in Madrid, Spain, where for more than a decade he acted with the Communist Movement in tasks related to peasant literacy and the anti-militarist movement against NATO. On his return to Uruguay, he published in the weekly Brecha, and became editor of Internacionales. He also worked for the environmental magazine Tierra Amiga from 1994 to 1995. Since 1986, as a journalist and researcher-militant, he has traveled to almost every country in Latin America, especially in the Andean region. Familiar with most of the movements in the region, Zibechi has collaborated with Argentine urban movements, Paraguayan peasants, Bolivian, Peruvian, Mapuche and Colombian indigenous communities in training and dissemination missions. All his theoretical work is directed towards understanding and defending the organizational processes of these movements.