After 15 July 2015, the Gazi neighborhood was among the areas targeted by state-led attacks in Turkey and North Kurdistan. The state launched a massive operation against the neighborhood, and in the span of almost six months, continuous operations were carried out against revolutionary structures that were strong in the area. As a result, many revolutionaries organized in the Gazi neighborhood were either arrested, forced into exile, or retreated into underground struggle. This process also saw the resurgence of special warfare tactics, allowing the state to establish relative control over the area.

The Turkish state’s special warfare tactics

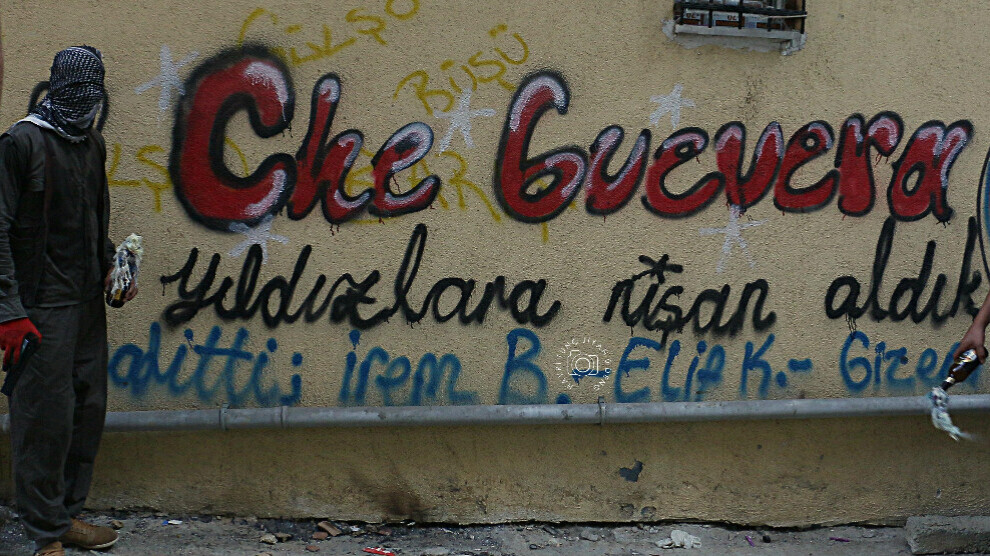

The Turkish state has developed a variety of special warfare methods, serving as an example to the world. During the period when structures like the Patriotic Democratic Youth Movement (YDG-H) were strong, television series emerged depicting gangs operating in neighborhoods, portraying them as fighting against corruption. These shows became particularly popular in poor neighborhoods, reinforcing the perception that the gangs were carrying out the daily tasks of revolutionaries. In these series, young men who avoided drugs and prostitution but carried weapons and engaged in corrupt relationships were presented as heroes.

With the state’s encouragement, these narratives rapidly spread among the youth in the neighborhoods. While revolutionaries were not even allowed to sell a magazine, armed youths began patrolling the streets, declaring themselves the "protectors" of the neighborhood.

At this point, it is important to highlight a critical gap: as repression against revolutionaries and the Kurdish Freedom Movement intensified, the void left behind was not swiftly or effectively filled by local political institutions. Due to their inability to organize unique solutions and their slow response, gang activities expanded rapidly.

The state’s crackdown on revolutionaries opened the way for gangs

The gangs that flourished in this vacuum had already existed in the Gazi neighborhood for the past decade. However, due to interventions by revolutionaries and their strong influence among the people, these gangs were unable to expand freely. After 2015, however, their numbers grew rapidly. Some gangs that refused to collaborate with the police were weakened or dispersed after police operations, while others that cooperated with the police and acted as informants began to thrive. Over time, the presence of these gangs facilitated the introduction of drugs into the neighborhood.

Gangs, which took a share of the drug trade, allowed drug sales but outsourced the actual distribution to outsiders. When public anger against drug sales rose, gang members would publicly "punish" a few drug dealers in an attempt to boost their reputation and prevent the resurgence of a revolutionary movement in the neighborhood.

After drugs entered the neighborhood, the next step was linking gangs to prostitution in an inseparable manner. Today, in the Gazi neighborhood, drug use has spread to the point where even elementary school children are affected. Young people seeking drugs, due to financial difficulties, become vulnerable to manipulation by gangs. At this stage, it was not the gangs but police officers trained in special warfare who stepped in.

For young people addicted to drugs, only two options remained: either they would be unable to access drugs, or they would have to comply with the demands of gangs and the state to secure their supply. Those who chose the latter became tools of the system—some became drug couriers for gangs, others were used to inform on revolutionaries, while many were coerced into prostitution in exchange for drug money.

For young people who had no involvement with drugs, another strategy was used. Growing up in poverty, they were bombarded with social media content showcasing a different lifestyle, tempting them with the promise of wealth, the latest smartphones, and easy money. Television shows that glorified gangs played a major role in this process. Presented with the opportunity to carry weapons, have easy access to cash, and live the lifestyle they envied, many young people saw gang membership as their only escape from poverty.

The state encouraged young people to flee abroad

While cracking down on revolutionaries and preventing the resurgence of revolutionary dynamics, the state remained passive in the face of crimes committed by gangs. Gang wars, territorial conflicts, drug-related shootings, and extortion had become so normalized that they were seen as part of "everyday life." Reports of attacks and shootouts emerged almost every hour. Yet, while police conducted high-profile raids against revolutionaries for distributing magazines, they largely ignored gang activities. Instead, the police relied on an informant network established through the gangs to monitor revolutionary movements.

In addition to enabling gang activities, the state implemented another strategy in the Gazi neighborhood—one that had already been used across Turkey and Bakur (North Kurdistan) in the last five years. By creating mass unemployment and widespread uncertainty about the future, the state subtly promoted migration as the only escape route. Through covert propaganda, people were encouraged to believe that they could find a better life abroad. At the same time, repression increased, especially against those who had no ties to gangs but maintained connections with revolutionaries.

As a result, thousands of young people from the Gazi neighborhood alone were forced to leave Turkey via illegal routes after 2015. This strategy, which targeted young people suffering from economic hardship and state repression, aimed to reduce revolutionary dynamics in the neighborhood. The state apparatus took no action against gangs involved in human smuggling, further facilitating this exodus.

Despite all repression, resistance continues

Today, Gazi Neighborhood has become a place where gangs operate freely and the state’s special warfare policies are in full effect. The state cracks down on any form of democratic protest while turning a blind eye to gang activities. Currently, the neighborhood is home to more than 20 different gangs, and access to firearms has become incredibly easy. More and more people are either moving out or considering leaving the area.

Despite these challenges, revolutionaries continue to exist. They persist in their efforts to offer hope and protect the neighborhood from corruption. The people of the neighborhood have also come to better appreciate the importance of the revolutionaries. Many residents I spoke with recalled how, during the time when revolutionaries were strong, the streets were safe—now, those same streets have turned into places of fear, with corruption growing day by day.

Since its establishment, Gazi Neighborhood has experienced the full force of state oppression and special warfare tactics. Yet, it still stands with its oppositional identity intact. Although gangs have gained ground, this does not mean revolutionaries have been defeated. Despite all the state repression, the neighborhood remains defiant.

A sense of silence prevails, but both the people and the state know that the Gazi neighborhood has not been defeated. On the 30th anniversary of the massacre, it is clear that despite all attempts, the state’s special warfare policies have ultimately failed in this poor neighborhood. Even without large-scale uprisings, the people of the neighborhood continue a quiet resistance, striving to preserve their history.