Following Abdullah Öcalan’s 27 February acll for Peace and a Democratic Society, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) held its 12th Congress on May 5–6 and declared that the Kurdish question had reached a point where it could now be resolved through democratic politics. In this regard, the PKK announced that it had fulfilled its historical mission. While concrete steps are expected from the Turkish state in response to these developments, recent statements have included calls for the parliament to assume its responsibility in this process.

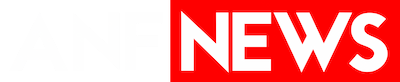

What are the conditions shaping this entire process, the 27 February call and the PKK’s congress declaration? Within these evolving circumstances, what kind of political framework is Öcalan putting forward? Political scientist Dr. Hasan Kılıç spoke to ANF about the crisis of capitalist modernity and the collapse of the old order, emphasizing the significance of the framework outlined by Öcalan in this context of transformation.

You often argue in your writings that “the liberal order is collapsing” and examine global restructuring through this perspective. In light of this, how do you interpret the 27 February call for Peace and a Democratic Society, especially in terms of the Middle East, which stands at the center of this transformation?

For quite some time, even the central institutions of capitalist modernity have debated that the current form of the system is no longer sustainable, economically, geopolitically, in terms of moral values, and in the norms it has produced. The end of the unipolar world has been discussed for decades. Meanwhile, during the neoliberal phase of capitalism, the system increasingly relied on finance capital as the primary form of capital accumulation. This path began to break down with the 2008 crisis, indicating the need for a new economic-political equation. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Western hegemony imposed and enforced ‘liberal norms’ across the globe. However, the rise of populist leaders, political and economic gridlocks, and the fact that class-based crises led large segments of society to shift politically toward the right, all these developments revealed that those norms could no longer resolve conflicts or establish mutual legitimacy. At the same time, experts at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) were declaring the post-World War II order to be collapsing, while the principle of ‘territorial sovereignty’, a cornerstone of that order, was rapidly losing its relevance.

In short, capitalist modernity is facing a multi-layered crisis, economic, political, cultural, and ethical, where each dimension feeds into the other. This crisis highlights the necessity of transformation in the existing world system. As a reflection of these crises, we are witnessing unprecedented levels of impoverishment and inequality in wealth distribution, the severe destruction of ecological systems, and a security-centered transformation of state structures. All these negative developments are affecting the lives of billions. Even the core institutions of capitalism have begun reporting that the current model is unsustainable and that it is paving the way for a perfect storm, a widespread rebellion of millions. This situation has triggered a global search for alternatives. For instance, discussions about a ‘Great Reset’ began at Davos, the symbolic temple of capitalism. NATO revised its strategic outlook. And in 2018, the United States (US), still the dominant global power, publicly stated that future wars would now occur between states.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the ‘liberal order’ has entered a deep and comprehensive crisis. Thus, Karl Marx’s famous assertion, “Force is the midwife of every old society pregnant with the new,” has once again come into play. In its search to establish a new order, capitalism has placed violence at the center.

When capitalist modernity deploys violence to create the new, it often turns the Middle East into a testing ground. What has been unfolding in the region since October 7 reflects a dual reality: the collapse of the old orders and the ignition of a struggle to shape the new. This reality has multiple dimensions.”

What are these dimensions?

First, the Assad regime, whose foundations trace back to the Cold War, has effectively been dismantled. This marks the end of a Cold War-oriented reading of the Middle East. Second, proxy forces are rapidly being eliminated, and some non-state actors are now being offered the option of integration into the system under the new order. In other words, as violence gives birth to the new, it simultaneously brings about serious risks and threats, but also major opportunities for all actors involved. The third dimension is that capitalist modernity aims to economically, politically, geopolitically, ethically, and culturally reshape the Middle East, using it as a testing ground for a model it hopes to export globally.

Looking back on history, we see clearly that the Middle East has always been a region where capitalism failed to take root. Confronting this reality leads to two options: either the peoples of the Middle East continue to wear a suit tailored by the forces of capitalist modernity, a suit that never fits, or they cut their own path and sever the umbilical cord themselves.

It is precisely at this crossroads that Mr. Öcalan’s 27 February call for Peace and a Democratic Society takes on its full meaning. The content of the call makes it clear that two world-historical phases, real socialism and the Cold War, have come to an end. Mr. Öcalan links the emergence and development of the PKK to these global historical conditions. In doing so, he indicates that with the disappearance of the conditions that gave rise to the PKK, a new phase has now begun. From its very first sentence, the call captures the spirit of the times and the depth of global and regional transformation with remarkable clarity. Mr. Öcalan recognizes that world-historical conditions have changed and that this shift calls for a bold response. In this context, he offers a new path and a new opening for the Middle East, Turkey, and the Kurdish people. To return to my earlier point, everyone in the Middle East today is navigating the future with some form of imagined option in hand. Mr. Öcalan, however, proposes a democratic communal future for the region. Among numerous visions, such as prolonging tensions in the name of Israel’s security, imposing a new order of exploitation and stabilization for Israel’s benefit, or reviving Neo-Ottomanist fantasies, his is a radically different and transformative alternative. He demonstrates both the reality and the courage of radically deconstructing everything that belongs to the old order. He shows that, if a democratic society is built through democratic consensus in Turkey and the broader Middle East, the peoples of the region can indeed sever their own umbilical cord and shape their destiny.

Ultimately, the 27 February call is not merely a response to the chaos of the present moment. It is the product of a mind that has calculated the global trajectory and its implications for the region with sharp foresight. It is a declaration that seeks not just to respond to crisis, but to begin constructing the future here and now. For this reason, describing it as ‘the Call of the Century’ is entirely appropriate.”

Following Mr. Öcalan’s call, the PKK announced its decision to dissolve itself. In many commentaries, it is emphasized that the fronts of a Third World War are expanding. In a time when war continues and many of the democratic rights gained after the Second World War are being rolled back, does this dissolution reflect the new global conditions?

If we think about whether there is a Third World War by relying on the imagery associated with the first two world wars, we are likely to be mistaken. Interpreting today’s world conflict through the visual and symbolic representations of past wars is not the right approach. That is because each world war had concrete economic, political, social, and cultural causes.

Today, we are experiencing a recession in the same economic-political, geopolitical, ethical, and moral structures that created the first two world wars. The displacement of hegemonic power, the multiple contradictions between competing global forces, the suspension of shared values that once held societies together, the spread of violence across nearly all regions of the world, the blockage in capital accumulation, and the dramatic rise in poverty and precariusness. These are all elements of our current reality. If we think of world wars not through images but through material conditions and cause-and-effect logic, then we clearly see that we are already living in a Third World War.

This war is not one that will be won solely through violence or its instruments. Violence is only one element of the Third World War and the order that is expected to follow it. It is not an irreplaceable or irreversible element.

To interpret the PKK’s dissolution decision solely through the lens of violence would be a serious oversight. Yes, this war has violent dimensions. But the struggle for the shape of the post-war order deserves a broader, deeper analysis. In this regard, the statement accompanying the dissolution includes a highly accurate observation: this is not an end, it is a new beginning.

The correct evaluation of current conditions suggests that the decision was made with the intention of taking part in the emerging global order, and within that order, to lead a revolutionary, democratic, and socialist struggle. What we are witnessing is a response to the present conjuncture and, at the same time, a forward-looking step that offers a perspective towards the future.”

Turkey has previously gone through a peace process. However, the conditions and context have changed. As we’ve already discussed, today’s realities present a different framework. In light of this, what is the current picture, at least in the near term, for the Kurds within this new reality, one that arguably transcends Turkey itself?

The earlier peace processes should not be seen as isolated episodes that ‘happened and ended.’ They must be viewed as part of a long-term political struggle, experiences and legacies that carry forward. The differences in context simply reflect the evolving global, regional, and national conditions. Today’s global search for a new order is generating new visions for how the Middle East should be reshaped. In this regard, Mr. Öcalan approaches the issue through four interrelated layers. At the first layer, the focus is on protecting the Kurdish people and guaranteeing their rights. The second involves democratizing Turkey. The third aims to establish an alternative democratic way of life in the Middle East. And the fourth envisions a globally resonant democratic socialist alternative. From the Kurdish perspective, the most foreseeable development in the near future is the end of a century-long imposed fate in the Middle East. It is a time for strengthening and advancing Kurdish gains, political, cultural, and social, and for positioning themselves as a reference point for democratic partnership in the region (and potentially the world) through alternative governance, economic models, gender liberation, and ecological approaches.

Turning our attention back to Turkey, we see that, unlike in previous peace processes, there is currently no significant opposition from the main opposition or other segments of society. However, one of the most current and sensitive points of debate has become the Treaty of Lausanne, which has been instrumentalized by certain political circles. How do you interpret the way this debate is being framed?

First of all, the norms, ethical codes, and moral values of the so-called ‘liberal order’ have lost their validity, which makes it difficult to understand the Peace and Democratic Society Process through the lens of global precedents. Some people describe it as a case of ‘peace first, then resolution,’ while others call it an ‘atypical process.’ These differing interpretations stem from this global transformation.

That said, there are several key aspects that distinguish this process from those in the past. First, due to global and regional developments, the process is receiving more international support than previous ones. This is because many actors are now committed to building a new global order, and doing so requires integrating both the Kurds and Turkey into their future visions. Second, the state appears more consolidated in its approach to resolving the issue compared to previous attempts. While there are still opposing forces both globally and within the state itself, the number of disruptive actors seems significantly lower. Third, the Kurdish freedom struggle has reached a new level. It has already dismantled the official denialist narrative. At one point, the dominant discourse shifted to: ‘Yes, Kurds exist, but they have no rights.’ That resistance was also overcome. Then came the position: ‘Kurds exist, but only individual rights can be granted, not collective ones.’ During that phase, efforts to foster right-wing tendencies among Kurds were encouraged, but even that point has been surpassed. Today, we are in a phase where collective Kurdish identity and collective rights are actively acknowledged and asserted.

It’s important not to lose sight of this accumulated reality when engaging with contemporary debates. The Lausanne debate, in this sense, is an attempt by opponents of the process to revive frozen historical fears in order to derail current progress. Their core strategy is to frame any critique of Lausanne as an attack on the republic or the state, and to use this manufactured perception to spread opposition to the process. But in reality, there is no rejection of the Treaty of Lausanne as a historical fact. Rather, what is being challenged is the anti-democratic and anti-Kurdish hostility produced by its consequences. The actual aim is to accept Lausanne as a historical truth, but to reshape its outcomes through democratization of the republic and transformation of the state into a more democratic entity.

And let us be clear: the opponents of this process are well aware of this reality. Their concern is not historical accuracy; their goal is to preserve their comfort within the existing order, to sustain Turkish supremacy and maintain colonial relationships as they are. So, while the surface-level debate may appear to be about Lausanne, the deeper issue is about resisting the continuation of colonialism and fighting for an equal, democratic life. It is a struggle between the maintenance of a singular, authoritarian regime and the realization of a democratic Turkey. It is a confrontation between the fantasy of re-colonizing the Kurds and the shared decolonization of both Kurds and Turks.