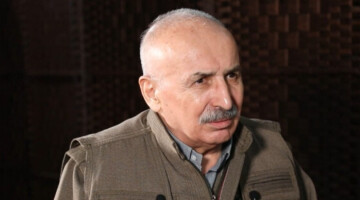

Zeynab Jalalian, Iran’s longest-serving and only female political prisoner serving a life sentence, marks 17 years behind bars.

Born in 1982 in the village of Dim Qeshlaq in Maku, West Azerbaijan Province, Jalalian has been imprisoned since 26 February 2008.

Jalalian is the only woman in the country serving a life sentence for political reasons. Over the years, she has been denied both the right to furlough and, for much of her imprisonment, the right to visit her family.

Despite suffering from several serious illnesses during her imprisonment, Jalalian has been repeatedly transferred between different prisons under harsh and unlawful conditions, often with physical violence.

In 2008, Jalalian was sentenced to death on charges of “enmity against God” (moharebeh), which was commuted to life imprisonment in 2011.

Throughout her detention and imprisonment, she has been subjected to severe torture. Even after 17 years in prison, she continues to face immense pressure from Iran’s security agencies, and any approval for medical treatment or temporary leave is contingent on her expressing remorse for her actions.

Her lawyer, Amir-Salar Davoudi, has consistently argued that her continued imprisonment is illegal under the revised Islamic Penal Code and that she must be released.

In 2016, the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention called for her immediate release, urging the Islamic Republic of Iran to take all necessary measures to compensate for the harm caused to her in accordance with international law.

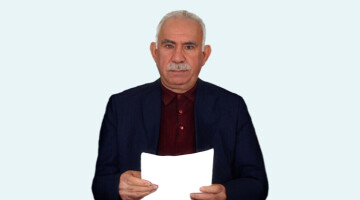

On the anniversary of her arrest, Jalalian wrote a letter from her prison in Yazd, giving just a glimpse of the immense suffering she has endured during her 17 years of imprisonment.

In the letter, which has been shared with the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN) for publication, she also appealed to the people of Iran, calling for unity and solidarity against executions, imprisonment, poverty, and other systemic injustices.

The full text of the letter reads as follows:

“My hands smell of flowers, and they blame me for plucking them. But no one ever thinks that perhaps I planted them myself.”

Oppression has left a deep wound in my heart, one that will never fade. I was a small dandelion, carrying a great message of freedom and liberty. On 26 February 2008, I set off on my journey to the beautiful city of Kermanshah, but the agents of tyranny kidnapped me along the way and took me to a foreign, unfamiliar place.

The black-clad officers had strange customs. In that dreadful place, no one was allowed to see another. They blindfolded me with a black cloth and would ask, “What is your name?”

I would answer, “My name is Zeynab.”

They would strike me and ask again, “What is your name?”

I would repeat, “My name is Zeynab.”

They would beat and torture me, then ask once more, “What is your name?”

Time and again, they would repeat the same question. Whether I answered or remained silent, it made no difference; the torture would continue. I could not comprehend their sick minds. In that dark place, no ray of light existed, for the agents of tyranny feared the light like bats.

After months, they transferred me to prison. The guards were women, but their cruelty surpassed even that of those faceless men. This pained me deeply.

After months of painful and exhausting waiting and uncertainty, one day, my name was called through the prison loudspeaker in a voice full of hatred and malice. They shackled my hands and feet and dragged me to a sham court. For three minutes, I debated with the judge about my mother tongue. He did not know me, nor did he listen to a word I said. So, on what basis did he sentence me to death? I do not know.

Later, they exiled me to Tehran. For six months, I endured unbearable pressure in the intelligence cells, forced to confess, coerced into giving an interview. After years, they brought my mother to Tehran under threats. My mother’s cries were beyond comprehension, beyond description. Enduring the pain of separation and the looming death sentence of her child was unbearable then, as it remains now. My mother’s suffering outweighed her patience, yet she never bowed to oppressors. She was the embodiment of profound sorrow; my words are surely incapable of describing it.

After six months, they returned me to Kermanshah. Repeatedly, I requested a transfer to my home province, yet I remained imprisoned in Kermanshah for seven years. Then, I was exiled to Khoy Prison, where I spent four years under severe psychological torment.

On the night when they had imposed silence and the prison had sunk into a deathly stillness, the agents of oppression returned, shackled me, and exiled me to Qarchak Prison. I was placed in a temporary ward and soon contracted COVID-19. I received no medical care, and my lungs suffered severe damage. I repeatedly requested a transfer, but my pleas were ignored. Left with no choice, I went on hunger strike.

After days of waiting, in the dead of night when the prisoners were asleep and only the sound of my coughs broke the silence, the agents of oppression came again. They shackled me, hand and foot, and forcibly exiled me to Kerman. There was no eye to read my plea, no ear to hear my words, no heart to offer sympathy or compassion. After months of isolation, deprived of phone calls, visits, and even a shopping card, on a sorrowful, dusty evening in Kerman, the prison officers, through deceit and force, exiled me back to Kermanshah.

And yet, after all these forced displacements, with a weary and ailing body, I closed my eyes to rest for a moment, but the voices of the guardians of purgatory denied me the chance to rest. They bound my hands and feet, blindfolded me, and exiled me to Yazd. Years have passed in this darkness, enduring hardship and deprivation, without phone calls, without visits. It has now been four years and four months that I have been imprisoned in Yazd.

In the darkness of this prison, I close my eyes. A faint image of life beyond these walls has remained in my imagination. I long for my mother’s warm embrace, my father’s loving gaze, my sister’s laughter, and even my brother’s frown. I long for the warm-hearted and hospitable people of Kurdistan, for the melodies of Kurdish songs. I miss the scent of the soil, the inverted tulips, the oak trees, and the squirrels feeding on their acorns. I miss the crystal-clear springs, the flowing rivers, the towering mountains, and the starlit nights.

Seventeen years have passed with all this suffering and longing… Seventeen years!

The Noble People of Iran,

The rulers of this regime are driving our homeland to ruin. They are killing our youth, executing them, or imprisoning them. They have plundered our natural resources and wealth. They have destroyed the country’s economy. Poverty and hunger are rampant.

How long will you remain silent in the face of these merciless destroyers?

How long will you struggle with poverty and starvation?

How long will you stand by and watch the destruction of your country and the future of your children in silence?

Is this life of humiliation truly our destiny?

Dear people of this land,

Let us stand united and cry out together:

No to murder, no to executions, no to prisons, no to poverty, no to hunger…

“If you tremble with indignation at every injustice, then you are a comrade of mine.”

— Che Guevara