In the case of Selahattin Demirtaş v. Turkey (No. 4), the European Court of Human Rights held that there had been several violations of the Convention. The case concerned the pre-trial detention, from 20 September 2019 onwards, of Selahattin Demirtaş, former co-chair of the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP).

In today’s Chamber judgment1 in the case of Selahattin Demirtaş v. Turkey (No. 4), the European Court of Human Rights held:

- unanimously that there had been a violation of Article 5 § 4 (right to a speedy decision on the lawfulness of detention) of the European Convention on Human Rights on account of the lack of a speedy judicial review by the Constitutional Court;

- by 6 votes to 1, that there had been a violation of Article 5 § 1 (right to liberty and security) of the Convention on account of the lack of reasonable suspicion that the applicant had committed an offence;

- by 6 votes to 1, that there had been a violation of Article 5 § 3 (right to be brought promptly before a judge) on account of the lack of relevant and sufficient reasons for keeping the applicant in pre-trial detention for more than four years;

- by 6 votes to 1, that there had been a violation of Article 5 § 4 on account of the lack of access by the applicant and his lawyer to the investigation file; and

- by 6 votes to 1, that there had been a violation of Article 18 (limitation on use of restrictions on rights) in conjunction with Article 5 § 1.

The Court observed in the present case that the applicant had been in detention since 4 November 2016. For most of that time, he had been held on charges relating to “the events of 6 to 8 October 2014”, among other things. The Grand Chamber had previously found the suspicion of public incitement to commit an offence in relation to those events to be insufficient in its Selahattin Demirtaş v. Turkey (No. 2) judgment of 22 December 2020. The applicant had subsequently been placed in pre-trial detention again, this time mainly for instigation to commit offences in connection with those same events – five years after they had taken place.

In particular, despite the clear connection between some of the events and charges that had led to the pre-trial detention of 4 November 2016 – as examined in the Court’s Grand Chamber judgment – and to the pre-trial detention of 20 September 2019, the authorities who had ordered the applicant’s second placement in pre-trial detention had provided no legal justification for the reclassification of the offences attributed to him, from “incitement” to “instigation” to commit an offence. Similarly, although the applicant had been accused of serious offences, their essential constituent elements could not reasonably be deemed to have been made out in the light of the existing evidence.

Considered as a whole, the circumstances showed that the measures taken by the authorities had been based on inadequate reasoning and had pursued an ulterior purpose, namely that of stifling public debate and limiting the scope of democratic debate. The Court concluded that the restriction of the applicant’s liberty from 20 September 2019 onwards had been imposed for purposes other than those prescribed by Article 5 of the Convention.

The applicant, Selahattin Demirtaş, is currently detained in Edirne Prison (Turkey). He was one of the co-chairs of the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), a pro-Kurdish political party, and a member of the Turkish Grand National Assembly.

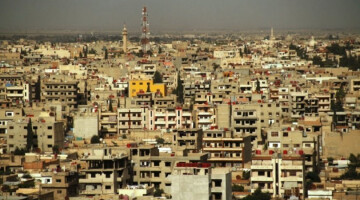

On 20 September 2019 the applicant, who had been deprived of his liberty since 4 November 2016, was placed in pre-trial detention on charges relating to “the events of 6 to 8 October 2014”. Those events had taken place after a “solution process” had been initiated in Turkey in 2012 with a view to finding a lasting, peaceful solution to the Kurdish question. In September and October 2014 members of the armed terrorist organisation Daesh (Islamic State) had launched an offensive on the Syrian town of Kobani, located 15 kilometres from the Turkish border town of Suruç. Armed clashes had taken place between Daesh forces and the YPG (People’s Protection Units, founded in Syria and regarded as a terrorist organisation by Turkey on account of its links with the PKK (Workers’ Party of Kurdistan, an armed terrorist organisation)). Following the outbreak of the clashes in Syria, the Turkish government had opened the country’s borders to thousands of Kurdish refugees, but had closed them in the direction of Syria in order to prevent volunteers from leaving to fight in Kobani. From 2 October 2014 onwards a large number of demonstrations had been held in Turkey and several non-governmental organisations (NGOs) had published statements calling for international solidarity with Kobani in response to Daesh’s siege of the city.

The demonstrations had become violent from 6 October 2014.

Following the lifting of the applicant’s parliamentary immunity, the Diyarbakır public prosecutor had decided to join the various criminal investigations in respect of the applicant together as a single case. The Government specified in particular that there had been only one criminal investigation concerning the events of 6 to 8 October 2014. The measures taken in the context of that case were the subject of the Grand Chamber judgment of 22 December 2020 in the case of Selahattin Demirtaş v. Turkey (No. 2).

On 4 November 2016, the public prosecutor had asked the Diyarbakır 2nd Magistrate’s Court to place the applicant in pre-trial detention for membership of an armed terrorist organisation (Article 314 of the Criminal Code) and public incitement to commit an offence (Article 214 § 1 of the Criminal Code). The charges were in part related to the events of 6 to 8 October 2014.

On 20 February 2017, the applicant had lodged an individual application with the Court concerning his pre-trial detention from 4 November 2016. In its judgment of 22 December 2020, the Grand Chamber had found that there had been a violation of Articles 5 §§ 1 and 3, 10 and 18 in conjunction with Article 5, and Article 3 of Protocol No. 1. However, it had found that there had been no violation of Article 5 § 4 of the Convention. It had further held, among other things, that the respondent State was to take all necessary measures to secure the applicant’s immediate release.

On 20 September 2019, the Ankara public prosecutor’s office applied to the Ankara Magistrate’s Court to have the applicant placed in pre-trial detention in the context of an investigation into the events of 6 to 8 October 2014, on the grounds that he was suspected of being one of the “instigators” of several serious offences.

The applicant lodged several objections against his continued pre-trial detention, all of which were dismissed.

On 7 January 2021, the Ankara 22nd Assize Court, after examining the Selahattin Demirtaş (No. 2)Grand Chamber judgment and the case file, ordered that the applicant be kept in pre-trial detention.

On 15 April 2021, the Ankara 19th Assize Court, which was dealing with the case that had seen the applicant first placed in pre-trial detention from 4 November 2016 to 2 September 2019, requested the Ankara 22nd Assize Court, which was examining the case relating to the applicant’s second placement in pre-trial detention on 20 September 2019, to join the two sets of criminal proceedings together as a single case. The Ankara 22nd Assize Court granted the request for joinder.

At hearings held between 26 and 31 December 2022, the Ankara 22nd Assize Court examined the applicant’s argument that the Court’s judgment of 22 December 2020 had not been executed and that the criminal proceedings in question had been pursued for political reasons. It found that the subject matter of the ongoing proceedings was different from that examined by the Court in its judgment of 22 December 2020.

At a hearing on 16 May 2024, the Ankara 22nd Assize Court found the applicant guilty on 11 counts and sentenced him in a summary judgment to 42 years’ imprisonment. It acquitted him on the other counts and decided not to impose a sanction on three counts, finding that they fell within the scope of the applicant’s parliamentary immunity. The criminal proceedings are still pending before the domestic courts.

The applicant lodged three individual applications with the Constitutional Court, complaining about his return to pre-trial detention on 20 September 2019. The Constitutional Court decided to join the three applications, which are currently pending before it.

Complaints, procedure and composition of the Court

Relying on Article 5 § 4 (right to a speedy decision on the lawfulness of detention), the applicant complained that the “speediness” requirement had not been complied with in the context of his application to the Constitutional Court.

Relying on Article 5 §§ 1 and 3 (right to liberty and security), the applicant submitted that his return to pre-trial detention on 20 September 2019 and his continued detention after that date had been in breach of the Convention. He alleged that that detention measure had been ordered on the basis of a mere legal reclassification of the facts previously examined by the Grand Chamber in its judgment of 22 December 2020. He further argued that the judicial decisions placing and then keeping him in pre-trial detention had contained insufficient reasons.

Relying on Article 5 § 4, he submitted that the lack of access to the investigation file had prevented him from effectively challenging the decisions ordering his pre-trial detention.

Relying on Article 10 (freedom of expression), he complained of a violation of his right under that provision.

Relying on Article 18 (limitation on use of restrictions on rights) in conjunction with Articles 5 and 10, the applicant submitted that the ulterior purpose behind his initial detention, as identified in the Grand Chamber judgment, had persisted during his detention from 20 September 2019.

The application was lodged with the European Court of Human Rights on 2 March 2020.

The Section President granted the following NGOs leave to intervene as third parties: Turkey Human Rights Litigation Support Project, Human Rights Watch and the International Commission of Jurists; and the freedom-of-expression association İfade Özgürlüğü Derneği (İFÖD).

Decision of the Court

Jurisdiction over subject matter of dispute (jurisdiction ratione materiae)

The Court considered that it had not previously examined the applicant’s grievances in the present case, since they concerned his continued detention after 20 September 2019. In consequence, the “new issue” resulted from the alleged continuation of the violation initially found by the Court. The Court was therefore satisfied that the issues raised by the application fell within its jurisdiction.

Article 5 § 4

According to the Court’s well-established case-law, individual applications lodged with the Constitutional Court, which were provided for in Article 19 of the Constitution to challenge deprivations of liberty, were in principle an effective remedy for the purposes of Article 35 § 1 of the Convention.

In the present case, however, the time taken by the Constitutional Court to decide the matter – more than four years – could not be regarded as “speedy” for the purposes of Article 5 § 4, even in the light of the particular circumstances of the case. For that reason, the Court observed that the individual application lodged with the Constitutional Court had proved incapable of satisfying the promptness requirements of Article 5 § 4 of the Convention.

The Court thus concluded that there had been a violation of Article 5 § 4 of the Convention. It followed that the applicant had not been required to make use of that remedy before bringing his complaints before the Court in the context of the present case.

Article 5 §§ 1 and 3

The Court observed that the period to be taken into consideration had started on 31 October 2019 and had been interrupted on 3 May 2021, then had resumed on 3 November 2021 and had come to an end on 16 May 2024, when the applicant had been convicted by the Assize Court. His pre-trial detention had therefore lasted slightly more than four years.

Furthermore, in the preliminary-proceedings report of 7 January 2021, the Assize Court had found that the detention ordered on 20 September 2019 had not fallen within the scope of the Grand Chamber judgment, pointing out that the proceedings pending before it concerned the applicant’s prior and subsequent activities in relation to the events of 6 to 8 October 2014.

In that regard, the Court noted that the events that had triggered the suspicion of incitement to commit an offence, within the meaning of Article 214 § 1 of the Criminal Code and as examined in the Grand Chamber judgment, were the same as the events that had given rise to the pre-trial detention of 20 September 2019. Certain evidence cited by the authorities had previously been examined in the Grand Chamber judgment. The remaining evidence, whether obtained before or after the detention order of 20 September 2019, was insufficient to satisfy an objective observer that the applicant could have committed the offences for which he had been placed in pre-trial detention.

The Court attached weight to the Assize Court’s findings that the events of 6 to 8 October 2014 had taken place against a tense background and in such circumstances as to have rendered it crucially important for politicians, when expressing themselves in public, not to make remarks that could trigger violent social conflict. Moreover, given the terrorism situation prevailing in Turkey for many years, a proven link between a legal political party and a terrorist organisation could be objectively regarded as a threat to democracy.

However, the judicial authorities appeared to have ordered the applicant’s return to pre-trial detention on the principal assumption that the Daesh attacks in Kobani had been part of a war between two terrorist organisations, Daesh and the PKK-linked PYD. They had held that in principle that war had had no reason to be of interest to Turkish citizens and that, if some had joined demonstrations and had committed acts of violence in response to the events in Kobani, it had been at the instigation of individuals such as the applicant.

Taken as a whole, the evidence relied on by the prosecution showed that the applicant, as co-chair of a pro-Kurdish political party, had met with the participants in the conflict – lawfully and with the State authorities’ approval – and had called for Daesh to be prevented from entering Kobani. Yet nothing in the applicant’s speeches or remarks made it possible to conclude that they had been incitement or instigation to perpetrate acts of violence. In the view of the Court, the authorities appeared to have presented those calls for demonstrations as an instigation to insurrection and other serious offences (homicide, assault, etc.), without any evidence to that effect.

In addition, the Court could not overlook the fact that the applicant, who had been provisionally released on 2 September 2019 in relation to similar charges, had been arrested again some five years after the events of 6 to 8 October 2014 and after the opening of the criminal investigation in 2014.

In the Court’s view, none of the decisions to place or keep the applicant in pre-trial detention had contained evidence capable of establishing a sufficient connection between his actions – primarily his political speeches and the interviews he had given during the armed clashes in Kobani in October 2014 – and the offences in question, for which he had been deprived of his liberty.

The Court concluded that in the present case there had been a violation of Article 5 § 1 (c) of the Convention on account of the lack of reasonable suspicion that the applicant had committed an offence during the events of 6 to 8 October 2014.

As regards the reasoning given in the decisions ordering the pre-trial detention and the duration of that measure, the Court observed that the applicant had been in detention since 4 November 2016. For most of that time, he had been held on charges relating to the events of 6 to 8 October 2014, among other things. The Grand Chamber had previously found the suspicion of public incitement to commit an offence in relation to those events to be insufficient in its judgment of 22 December 2020. The applicant had subsequently been placed in pre-trial detention again, this time mainly for instigation to commit offences in connection with those same events – five years after they had taken place. In particular, the domestic judicial authorities had not considered alternative measures to pre-trial detention.

The Court found that there had not been relevant and sufficient reasons for keeping the applicant in pre-trial detention for more than four years. There had accordingly been a violation of Article 5 § 3 of the Convention in the present case.

Article 5 § 4

The Court considered that neither the applicant nor his lawyers, all of whom had been unjustifiably prevented from accessing the investigation file, had had the opportunity to properly contest the reasons given for the applicant’s pre-trial detention. There had accordingly been a violation of Article 5 § 4.

Article 10

Given its findings under Article 5 § 1 (c), the Court considered that there was no need to examine separately the merits of the applicant’s complaint under Article 10 of the Convention.

Article 18

First, in the view of the Court, an analysis of the applicant’s detention after 20 September 2019 under Article 18 could not in the present case be divorced from the Grand Chamber’s finding as to his initial detention, which had been found to be in breach of Article 18 in conjunction with Article 5.

When the Grand Chamber had examined the issue of compliance with Article 18, it had considered not only the applicant’s pre-trial detention between 4 November 2016 and 7 December 2018, but also the circumstances surrounding his return to pre-trial detention on 20 September 2019 in the context of a fresh investigation opened by the Ankara public prosecutor’s office, which also formed the subject matter of the present application. The Grand Chamber had found that, in view of the applicant’s immediate return to pre-trial detention on 20 September 2019 and the speech given by the Turkish President the next day, the domestic authorities had not appeared to be particularly interested in the applicant’s suspected involvement in an offence allegedly committed between 6 and 8 October 2014, some five years previously, but rather in keeping him detained, thereby preventing him from carrying out his political activities.

In particular, despite the clear connection between some of the events and charges that had led to the pre-trial detention of 4 November 2016 – as examined in the Grand Chamber judgment – and to the pre-trial detention of 20 September 2019, the authorities who had ordered the applicant’s second placement in pre-trial detention had provided no legal justification for the reclassification of the offences attributed to him, from “incitement” to “instigation” to commit an offence. Similarly, although the applicant had been accused of serious offences, their essential constituent elements could not reasonably be deemed to have been made out in the light of the existing evidence.

Second, the Court also considered it crucial that some five years had elapsed between the events giving rise to the applicant’s detention and his return to pre-trial detention on 20 September 2019. It did not appear from the case file that the judicial authorities that had dealt with the matter just after the events of 6 to 8 October 2014 had classified the remarks in question as “instigation” to acts of violence. Nor had it been argued that, in the Assize Courts’ judgments convicting demonstrators of such acts, the relevant courts had identified any connection between the remarks made by the applicant and his party, on the one hand, and those offences, on the other.

Third, the applicant and the third-party interveners, referring to a number of international instruments, had emphasised the control exercised by the executive over the justice system. The Court referred to the findings of the Venice Commission as to judicial independence.

Fourth, in the bill of indictment, the public prosecutor’s office had made reference to a number of political speeches on various topical issues made by the applicant between 2013 and 2019 as co-chair of a political party or as a significant political figure. It had not, however, indicated how they were relevant to its accusations. The inclusion of such elements undermined the prosecution’s credibility and could be considered such as to confirm the applicant’s assertion that the measures taken against him pursued an ulterior purpose, namely that of limiting freedom of political debate.

Considered as a whole, the circumstances showed that the measures taken by the authorities had been based on inadequate reasoning and had pursued an ulterior purpose, namely that of stifling public debate and limiting the scope of democratic debate. The Court concluded that the restriction of the applicant’s liberty from 20 September 2019 onwards had been imposed for purposes other than those prescribed by Article 5 of the Convention. There had accordingly been a violation of Article 18 of the Convention in conjunction with Article 5.

Just satisfaction (Article 41)

The Court held, by 6 votes to 1, that Turkey was to pay the applicant 3,245 euros (EUR) in respect of pecuniary damage, EUR 32,500 in respect of non-pecuniary damage and EUR 20,000 in respect of costs and expenses.