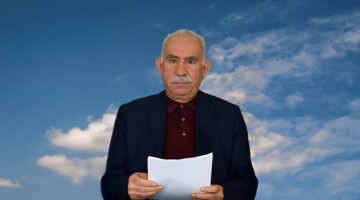

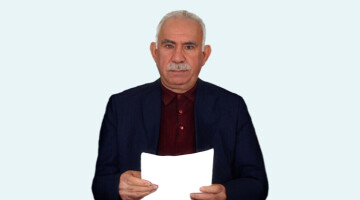

In the second part of this interview, Professor Hamit Bozarslan spoke about Abdullah Öcalan's call as well as recent developments in Northern and Eastern Syria.

The first part of the interview can be read here.

We have discussed the PKK’s fifty-year struggle and the historical background leading up to it. Today, we are witnessing a historic call from Abdullah Öcalan. In a previous interview, you mentioned that the existence and legitimacy of the Kurdish issue were still not acknowledged. At this point, has the existence of the Kurdish issue been officially recognized?

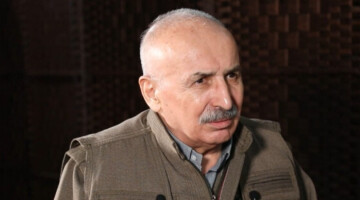

No, it has definitely not been officially recognized. However, there has been a slight change compared to five or six months ago. In this change, we see that the regime has been forced to re-legitimize Öcalan. Everyone has now realized the strong link between Öcalan and the Kurdish issue. The expectation from Öcalan was that, in his first statements, he would say, ‘I founded this terrorist organization, and I am dissolving it,’ without mentioning the Kurdish issue at all. However, when we look at Öcalan’s statements, we see quite the opposite—he speaks of a century-long Kurdish issue and frames the PKK’s guerrilla war not as a matter of terrorism but as an issue of violence that must be understood within its historical conditions. Thus, Öcalan’s message is clear: ‘We are not a terrorist organization. The Kurdish issue is not a terrorism problem; it is a national issue.’

Reading between the lines of this call, this is the reality that emerges. Therefore, it is difficult to predict how much longer the Kurdish issue can continue to be denied.

However, when we look at Erdoğan’s and the Minister of National Defense’s statements, it is clear that the state still perceives the Kurdish issue as either a terrorism or an imperialism-related matter. Yet, we are starting to hear some exceptions and dissenting voices. For instance, Numan Kurtulmuş is one of the figures who, in some way, acknowledges the existence of the Kurdish issue. Bülent Arınç, in his speech in Erbil, almost had to admit that the Kurdish issue is a national issue. Compared to six months ago, there are now more dissenting voices within the ruling bloc. Even in Devlet Bahçeli’s rhetoric, some shifts can be observed.

The fact that Öcalan is no longer being referred to solely as a ‘terrorist leader’ but also as the founding leader of the PKK indicates this shift. So, there are some advancements, but there is still no institutional state policy that recognizes the Kurdish issue as a legitimate reality.

I describe these developments as ‘small’ because they have not yet transformed into long-term, institutionalized changes. There are many small developments, such as the Republican People's Party (CHP) leader Özgür Özel’s remarks while receiving a delegation from the

Peoples' Equality and Democracy Party (DEM Party). Will these small developments gradually lead to a new institutional approach, a shift in the state’s discourse, and the recognition of the Kurdish issue both in Turkey and the Middle East? I remain quite hesitant. However, despite everything, it is clear that the process should not be obstructed. Or at the very least, the Kurdish side should not be the ones responsible for blocking it.

You interpret Abdullah Öcalan’s statements more in terms of what they do not say or do not include. You highlighted critical aspects regarding the PKK’s emergence. Now, when we look at Öcalan’s call, we see a declaration that is firmly grounded in historical context. At this stage, how should Öcalan’s call for change and transformation within the PKK be understood?

At this point, it is difficult to know what is happening behind the scenes. However, when we examine the PKK’s evolution over the past twenty years, we see that the organization has repeatedly stated on various occasions that the era of armed struggle is coming to an end and that a new historical phase must begin. In other words, we are not facing an entirely new phenomenon, but rather new conditions. The peace process between 2013 and 2015 ultimately collapsed due to several factors, including Erdoğan and the ruling bloc’s refusal to accept it, the rejection of the process by radical nationalism in Turkey, and developments in Syria. Therefore, while it is possible to discuss the opening of a new phase today, this possibility is still filled with uncertainties.

For this process to evolve into a permanent transformation, certain aspects must be extended over the long term, institutionalized, and legitimized. Even now, we cannot be certain that those engaging in talks with Öcalan will not face arrest tomorrow. In other words, the situation remains entirely ambiguous. Many things are possible, but nothing is certain.

From my perspective, for the past decade, the heart of Kurdistan has been beating in Rojava. Today, the most critical issue is the protection of Rojava and the securing of its status. When we analyze Öcalan’s statements, we do not see any indication that Syrian Kurds should dissolve themselves and become ordinary Syrian citizens or that Syria should revert to being the 'Syrian Arab Republic.' On the contrary, Öcalan’s call appears to be directed explicitly at the PKK and its affiliated armed units. At this moment, the most crucial issue seems to be persuading Turkey to recognize the legitimacy of Rojava and establishing a roadmap for this.

Following Mr. Öcalan’s call, the PKK released a statement indicating that disarmament could be discussed. What would laying down arms mean for the PKK? Does this signify the end of the organization?

No, it definitely does not mean that the PKK’s struggle has come to an end. The PKK, in one way or another, continues and will continue to exist and struggle. Today, the PKK’s armed activities are largely limited to responding to Turkish military attacks. However, when we take a broader perspective, we see a highly dynamic Kurdish society, particularly in Turkish Kurdistan and the diaspora.

Within these societal dynamics, 99% of activities are already conducted in non-military spheres. These are not underground or secret activities; on the contrary, they take place openly, in the public eye. Today, a Kurdish politician who decides to run for mayor is fully aware that they risk arrest at any moment. A Kurdish journalist who openly expresses their identity faces the same threat. Even an academic writing a Kurdish-language textbook for children risks pressure and imprisonment.

Despite all this, the Kurdish movement is no longer an underground movement. On the contrary, the biggest driving force behind Kurdish politics and struggle now unfolds in the open, in front of society. Kurdish society has reached this point. It is no longer possible to say that clandestine activities constitute a determining factor in the Kurdish movement. The social dynamic, in every way, is now a visible and public dynamic.

With the fall of the Assad regime, the balance of power in the country continues to shift rapidly. In this process, General Commander of SDF, Mazloum Abdi and the leader of HTS, the jihadist group in power in Syria, Ahmed Al-Sharaa (Al-Jolani), signed an eight-point agreement that serves as a roadmap. How do you interpret this agreement, and what does it mean?

This is a very recent and historic development, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions at this stage. However, it is important to recall the key points emphasized by Mazloum Abdi in the context of this agreement. The most striking aspect is the apparent acceptance of the principle of decentralization. It is widely understood that the current Autonomous Administration will undergo changes, but the crucial question is: What will be the scope of these changes? Will there be an Autonomous Administration limited to Kurdish regions, or will a broader autonomous governance structure be established that extends beyond Kurdish territories? What will the institutional framework of this new administration look like? These questions remain unanswered for now. However, the main point of contention between the Kurds and HTS, which can be described as a militia regime, has been the issue of decentralization. Based on Mazloum Abdi’s statements, it appears that a common understanding has been reached on this matter.

Another significant provision in the agreement is the issue of "transferring existing institutions to the state." This does not mean the complete dismantling of existing structures. If this transfer takes place within the framework of decentralization, it also implies preserving or formally recognizing a certain level of autonomy. However, as I mentioned earlier, it is still too early to make a definitive assessment of this process. The agreement is relatively short, recognizing the Kurdish issue, the status of Kurds in Syria, and the need for their rights to be constitutionally safeguarded. Beyond that, it is currently difficult to make further interpretations. However, if decentralization has indeed been accepted, it suggests that Kurdish institutions will be maintained in some form, though the exact name and structure of this entity remain uncertain.

At the same time, extreme caution is necessary. We have seen what happened in Latakia as what occurred there was a massacre of immense scale. The mobilization of pro-Bashar al-Assad forces and the killing of a thousand civilians cannot be justified in any way. This atrocity evokes memories of the great massacres in Ottoman and Turkish history, particularly those targeting Alawites. Even more concerning is the fact that HTS refuses to take responsibility for these massacres. This stance suggests either that HTS lacks control over other militia forces or that it is displaying an extreme level of hypocrisy. Moving forward, we do not know whether a strengthened regime will adopt a different strategy toward the Kurds. Therefore, the Kurds must be extremely vigilant. For now, the presence of the United States in the region remains an important guarantee for the Kurds. However, the duration of this presence is uncertain. Still, at least for the time being, the continued presence of the U.S. provides a level of security for the Kurds.

We have transitioned from an era where Kurdish existence was denied to a period where the constitutional protection of all Kurdish rights is being debated. One of the key provisions of the agreement states: "The Kurdish community is an indigenous part of the Syrian state, and the Syrian state guarantees their citizenship and all constitutional rights." Considering this provision in particular, as well as the overall content of the agreement, can this be regarded as a success for the Kurds?

If these principles are fully implemented, it will be a significant achievement for the Kurds. This provision marks the first time in Syria’s century-long history that Kurds are officially recognized as a fundamental component of the country. This recognition has been a long-standing goal of Kurdish intellectuals and political movements in Syria. From a historical perspective, particularly in the 1920s and later during the radical shifts of the 1950s and 1960s, Kurds found themselves navigating between two radical movements: one aimed at integrating into Syrian society and another focused on being part of Kurdistan. This is a critical distinction, Kurds are being acknowledged as part of Syria, yet they are also being recognized as Kurds. Recognizing Kurds as Kurds inherently acknowledges their connection to Kurdistan as well.

A similar process can be observed in Iraq. During the 2000s, Iraq experienced both a "re-Iraqization" and a "re-Kurdistanization", two interconnected processes. If the Kurds in Syria are constitutionally recognized as part of the country, this would be a historic milestone for them. However, caution is necessary. HTS is currently quite weak, and transforming a militia force into a full-fledged state is an immense challenge. It remains unclear whether HTS truly envisions a secular, democratic, and pluralistic Syria. Furthermore, whether HTS can effectively control other militia groups is highly uncertain. Reports indicate that some of the militias responsible for the massacres of Alawites are the same groups that participated in the ethnic cleansing in Afrin (Efrîn). Some of these militias have received direct support from Turkey or consist of mercenaries funded and armed by the Turkish state.

HTS must dismantle these groups, not just disarm them, but completely eliminate their presence. Whether HTS is capable of doing this remains uncertain. Therefore, the Kurds must focus on advancing the constitutional process and working toward the establishment of a decentralized Syria. However, while doing so, they must also remain acutely aware of the uncertainties of the future and proceed with extreme caution.

Before traveling to Damascus, General Commander of SDF Mazloum Abdi reportedly held a meeting with various ethnic and religious groups within the Autonomous Administration. One of the key provisions of the agreement guarantees the right of all Syrians, regardless of religious or ethnic background, to participate in the political process and state institutions based on authority and responsibility. In essence, this clause mirrors the existing system in Rojava. But is it feasible to implement this provision? Is there an effort to extend the Rojava model to all of Syria?

I believe that the future Syria will not be a country shaped solely by constitutional principles. Instead, a multilayered structure may emerge, where different regions implement different social and political formulas. For example, when looking at Christians, they do not have a defined territorial base. There is no concentrated Christian-majority region, yet their rights and representation must be safeguarded. The Druze, on the other hand, hold a distinct position. Despite being entirely Arab in identity, they possess both territorial and religious uniqueness in the border region. As for the Alawites, they do have a specific regional base, but that area is also home to a significant Sunni population.

When it comes to Kurdistan, meaning present-day Rojava, we can speak of a dual structure. First, there is Rojava as a region predominantly inhabited by Kurds. Second, there is a broader Autonomous Region under Kurdish control, extending beyond Kurdistan’s historical boundaries. Initially, the Kurds did not intend to move toward Raqqa, but because it served as the second capital of ISIS, capturing the city became unavoidable. It was a necessity in the fight to eliminate ISIS. The key question for the future is whether the Kurdish movement wants to maintain control over Raqqa. Or, if the Arab population there demands the continuation of the Autonomous Administration, would the Kurds withdraw? At this stage, there are no clear answers to these questions.

For this reason, representation is not an issue that can be resolved with a single formula. Unless it is violently sabotaged, as in Latakia, we are likely to witness a long-term process in which different regions implement different governance models. These models cannot be implemented overnight; we may need to think in terms of the 2030s or even 2035. The greatest advantage for the Kurds is that they have been governing themselves for the past twelve years. Institutionally, they are far ahead of other groups. Municipalities, schools, hospitals, and Kurdish-language education systems are in place. Additionally, there are three universities in Kurdistan. However, despite these advancements, it will take time to determine the final map of Syria’s future.

Officials from the Autonomous Administration stated that the agreement aligns with the letter sent by Kurdish People's Leader Abdullah Öcalan to Rojava, emphasizing that this development signifies the Kurds becoming a recognized partner in the Syrian state. What are your thoughts on this?

Since we do not know the full content of Öcalan’s letter, it is difficult to make a direct assessment. However, based on the information I have gathered, Öcalan reportedly said, “There is no reason for the Kurds to exhaust their forces at the Tishrin Dam. The Kurds need to go to Damascus.” This suggests that he might have emphasized the need to resolve many issues not only through armed struggle but also by directly engaging with Damascus and negotiating. It is possible that he expressed such a perspective, which would indicate that recent developments have unfolded in line with Öcalan’s expectations or recommendations.

The idea of the Kurds ‘becoming a partner in the state’ most likely refers to their constitutional recognition as a fundamental component of Syria. Moreover, this recognition could be at a relatively high level. For instance, it is uncertain whether Mazloum Abdi might hold a significant position as a general in the future Syrian military. If Mazloum Abdi were to secure a position within the Syrian army while maintaining his Kurdish identity and preserving Kurdish military units, this would be a highly significant development.

A comparable situation can be observed in Iraqi Kurdistan. Of course, there have been serious challenges, and unresolved issues remain, particularly the Kirkuk question must not be overlooked. However, at the same time, the Kurds play a decisive role in Iraqi politics. Today, the formation of any government in Iraq is highly dependent on Kurdish support. The Kurds not only have their own parliament but also hold considerable influence within the Iraqi parliament.

While the Kurdish side remains steadfast in defending Rojava’s status, the Turkish state has pursued a policy aimed at eradicating the Kurdish presence in the region since the beginning of the Syrian war. In recent developments, Rojava’s military structure has repeatedly been used as a pretext by Turkey. However, with this agreement, Turkey’s justifications have essentially been rendered void. Does this signify the collapse of Turkey’s Rojava and Syria policy?

Yes, you are absolutely right on this point. Turkey’s hypothesis that 'there is no Kurdish issue in Syria' has completely collapsed. We now have an eight-point agreement signed by Ahmed Al-Sharaa (Al-Jolani). The mere existence of this agreement signifies that the Kurdish reality in Syria has been recognized. Moreover, the agreement was signed by Mazloum Abdi, whom Turkey has long labeled as a 'terrorist leader.' This, in turn, demonstrates that Mazloum Abdi is now recognized as a legitimate political actor in Syria. He is not only acknowledged as a legitimate Kurdish representative but also as a key figure representing the Autonomous Administration. And this recognition is not confined to Kurdistan alone, it extends to Syria as a whole, where he is now seen as a legitimate actor in the broader political landscape.

From this perspective, as you pointed out, Turkey’s reading of the region, its political impositions, and its attempts to legitimize its strategy of violence have all collapsed. However, Turkey is deeply entrenched in rigid ideological positions and radical nationalist sentiments. Predicting how such an ideology will respond to these developments is difficult. If Turkey were to act rationally, it would welcome these developments, acknowledge Rojava’s existence, and even attempt to leverage Rojava’s position to gain influence in Syria. A power seeking to maintain a foothold in Syria putting aside ethical concerns and evaluating the situation purely from a geostrategic standpoint would recognize Rojava’s legitimacy. Any external power that acknowledges Rojava’s legitimacy could gain a much stronger position in Syria. However, the issue here is one of rationality. The real question is whether Turkey’s current leadership is capable of adopting such a rational stance. At this stage, it is difficult to predict.

It has been reported that the United States and certain international powers played a role in the agreement signed between Mazloum Abdi, and Ahmed Al-Sharaa (Al-Jolani). Does the involvement of these powers indicate that Rojava’s status is beginning to gain international recognition?

Yes, at this stage, we can say that such a recognition is emerging, but it has not yet reached an official or legal level. It is known that two days before the agreement was signed, a U.S. representative met with Mazloum Abdi for significant negotiations. These discussions were most likely related to the continuation of U.S. influence in the region and relations with Damascus. Additionally, reports indicate that Mazloum Abdi traveled to Damascus aboard a U.S. helicopter to sign the agreement. All of these developments point to a form of de facto recognition. However, the critical issue is transforming this de facto recognition into a legally binding status, one that engages states and the international community in a legal framework. When recognition remains only de facto, its future remains uncertain. This is why the Kurds must approach this process with extreme caution.

The future remains unpredictable, and it is difficult to determine how things will unfold. This is precisely why the presence of the U.S. in the region holds immense strategic importance. Careful and calculated steps must be taken during this period. On the other hand, much of Turkey’s rhetoric over the past decade has effectively collapsed. If the Damascus administration, which Turkey has supported, is now engaging with Mazloum Abdi, signing an agreement with him, and recognizing him as a legitimate actor in Syria, then Turkey loses its ability to frame this as 'negotiating with terrorists.' The Turkish state can no longer sustain its narrative that any engagement with Mazloum Abdi constitutes legitimizing terrorism.