On the night of 28 December 2011, Turkish Armed Forces' warplanes bombed an area on the border with Southern Kurdistan (Iraqi Kurdistan). The bombs killed 34 mostly young men on their way back from the Iraqi border they had crossed for "Border Trade" from the villages of Gülyazı (Bejuh) and Ortasu (Roboskî) in Şırnak’s (Şirnex) Uludere (Qileban) district.

The 34 victims were mostly belonging to the same families.

The villages of Roboskî and Bejuh were formed in 90's, when scores of people who were driven away from their evacuated villages, settled here near their relatives after their own lands and villages were evacuated by security forces of the Turkish Republic State.

The Turkish state laid mines across the lands around villages, which claimed the life of five people and left more than 20 others cripple so far. It would be hard to estimate the number of animals killed in mine explosions.

What is called "trade border", "caravan", "boundary" and what the state and its supporters call "smuggling" is the only opportunity for the people there to earn their living. They do not call it "smuggling" for the people here have never recognized the borders that relevant authorities imposed on them. They have been involved in "smuggling" since the time of their grandfathers as they have always had families, relatives or fields in Iraq, on the "other side" of the "border". As a matter of fact, there is no physical border in question, at the borderline there is only a stone with number 15 carved on it.

On these "national" lands, the remainder of an empire which expanded to three continents, people have been living social traumas beyond the empire's habitat. People are living with the trauma of a history of big massacres from Armenian Genocide to Dersim Genocide, from events of 6-7 September to military coups, from Çorum and Mamak Massacres to Madımak Massacre, from the 28 February Massacre in the village of Zanqirt (Bilge) to that in the village of Roboski. That deplorable massacre which went down in history as "Roboski Massacre" is a ring of this trauma chain.

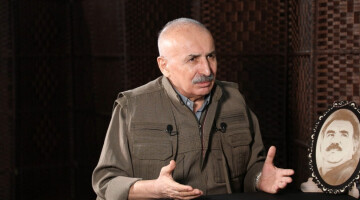

In the evening of 28 December 2011, a group of people from the village went to do what they would normally do, "border trade". They went as usual within the knowledge and sight of local military units which had already emptied all military sites in the region and smoothed the way for border traders one month before the massacre took place. According to Murat Karayılan, KCK (Kurdistan Communities Union) Executive Council President, the area where the bombardment was carried out, has never been used by the PKK (Kurdistan Workers Party) since 1991 for the very smooth feature of the area.

On their way back from the border, the people in the group saw that soldiers had closed all three alternative ways to the village. They were subjected to a warning shot and artillery fire without being warned to stop. Ubeydullah Encü, father of 13 years-old Muhammed Encü who also lost his life that night, told that he had called the commander at the military post near the village and informed him that a group of people, including his child, was in the mentioned area. The commander told Encü that he knew about the people there and replied that they just fired a warning shot for intimidation. However, things didn't work that way and their children were targeted by the bombs of F-16 warplanes.

The villagers who rushed to the scene after the bombardment tell that 13 people were still alive and the bodies of others were still burning when they reached there. These people who on the way encountered soldiers returning from the region on order had to carry the wounded survivors with their own efforts as no officials went to the scene despite the fact that they had informed all authorities soon after the incident. Soldiers in the nearby military posts denied health care teams from Şırnak permission to go to the scene as the bodies of victims and the injured were being taken away from there. "We gathered the parts of their bodies and tried to take them to our village in the saddles of donkeys that survived the bombardment." All villagers who were there that day know that many of the wounded bled and/or freeze to death. 17 out of 34 victims were children aged under 18. Anyone who visits the village once can apparently see what sort of a trauma it has caused. The people in the village have been suffering from psychological depression since that day, six years ago.

This indisputably newsworthy tragic event was however not reported by the Turkish media for more than 12 hours, while some of the very few who wanted to report it were hindered by their directors. As state authorities started to make official statements on the massacre, the media resorted to euphemism and reported it under the title "incident near Iraqi border". The debates in the following days didn't go beyond asking "whether the victims were smugglers or terrorists" and "whether the incident was an accident, a negligence or a trap".

The western side of Turkey's society organized all night long new year celebrations three days later, as if there had been no massacre, while people in Roboski went through a sorrowful night after seeing the bodies of their beloved brothers and sons blown to pieces.

By extending thanks to the Chief of Defence and military command echelon for the "sensitivity they displayed" after the massacre, the then Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan gave the sign of the attitude the state would have from then on.

According to the testimony of villagers, the Turkish authorities who didn't allow ambulances and helicopters to go to the scene on the night of the massacre sent a team to the scene one day later and made it gather all remains (parts of people's and donkey's bodies) in the area and set them on fire, obfuscated the evidences in other words. The Prosecutor who described the massacre as a mistake and promised not to arrest anyone had a team investigate the crime scene with a helicopter from the air and wrote on the reports that "they saw nothing" at the scene.

The process progressed so imprecisely that even the names and numbers of victims were wrongly recorded on autopsy reports and therefore on the reports of Human Rights Organizations that grounded their information on these reports. Following a series of reporting works in the village soon after the incident, establishments such as MAZLUMDER, Human Rights Association (IHD), Diyarbakır Bar Association, Confederation of Public Workers' Union (KESK) and Justice Platform for Brotherhood (KİAP) agreed that the incident was indeed a "massacre".

That night, as Ferhat Encü, brother of one of the victims and an MP for HDP, puts it: "The state became a bomb and rained on us from the air, making our children and relatives totally shocked about what was going on. The state which spilt out death and left us alone with our dead relatives furthermore uttered threats after the massacre and tried to prevent us from burying the victims side by side".