BTI classifies Turkey as an autocracy for the first time

Of the 137 countries currently examined, the BTI classifies 74 as democracies and 63 as autocracies.

Of the 137 countries currently examined, the BTI classifies 74 as democracies and 63 as autocracies.

Restricted freedom of expression, a gagged press or disempowered constitutional courts - as a rule, these are characteristics of autocracies. But the Bertelsmann Stiftung's latest Transformation Index shows that the rule of law and political freedoms are also being eroded in an increasing number of democracies. The main causes are abuse of power and cronyism, which increase economic inequality and contribute to social cleavages. The effects of the corona pandemic threaten to intensify these developments.

The number of people who are governed poorly and less democratically is increasing worldwide. For the sixth time in a row, the ratings of Bertelsmann Stiftung's international Transformation Index (BTI) for the quality of democracy, market economy and governance have dropped, now to their lowest level since the BTI survey began. Since 2004, the index has assessed political and economic developments in developing and transition countries every two years. Of the 137 countries currently examined, the BTI classifies 74 as democracies and 63 as autocracies.

Weak democracies, repressive autocracies

The current share of democracies in the countries examined is 54 percent. This is not a major step backwards compared to the BTI 2010 (57 percent). The declining global average scores for democracy are essentially the result of weaker democracies and more repressive autocracies. For example, the separation of powers has been significantly eroded in 60 states over the past decade. In 58 countries, demonstration rights and freedom of organization have been restricted. Freedom of opinion and freedom of the press have even been reduced in half of all the countries examined. This negative trend continues almost unabated in the current BTI.

In about one-fifth of the developing and transition countries studied, the quality of democracy has declined or the level of repression has risen again. The Hungarian emergency legislation with its indefinite suspension of the separation of powers exemplifies the fact that the fight against COVID-19 will further promote the trend towards a strong executive branch and will be instrumentalized by some heads of state to consolidate authoritarian structures.

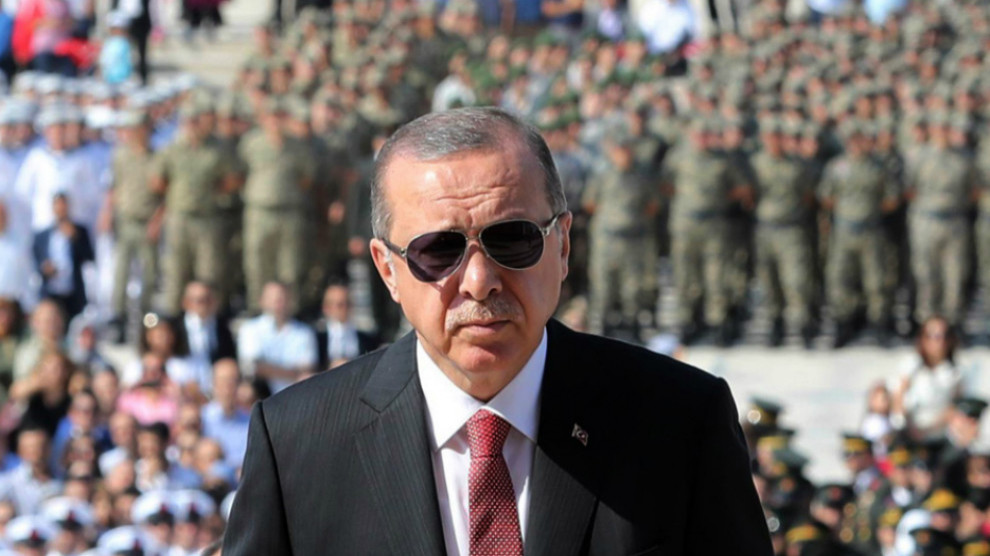

According to the authors, the dismantling of the rule of law and civil liberties in once-stable democracies is striking. Examples of this are Hindu nationalism in India, right-wing populism in Brazil or the authoritarian course of EU member Hungary. The developments in these countries are representative of the increasing political polarization that is also shaking consolidated democracies. This is often accompanied by the suppression of opposition and ethnic or religious minorities. This is also the case in Turkey, which the authors classify as an autocracy for the first time due to massive restrictions on the freedom of the press, gross disregard for civil rights and the undermining of the separation of powers.

“Nationalism and nepotism are not new, but they have become acceptable worldwide. Even former democratic frontrunners who, like Poland or Hungary, are located in the heart of Europe are now showing alarming setbacks when it comes to the rule of law and the quality of democracy,” says Brigitte Mohn, member of Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Executive Board.

Lack of responses to political and socioeconomic challenges

Causes for the destabilization of established political orders are the inability of political actors to solve problems, clientelism and a lack of willingness to compromise. The majority of governments fail to find answers to the problem of economic and social exclusion of broad sections of the population. Poverty and inequality are widespread in 76 of 137 countries, including 46 of 50 African countries. In view of rudimentary health systems and precarious living conditions, the weakest members of these societies are particularly vulnerable to the devastating effects of the current pandemic.

These chronic deficiencies are often the consequences of a concentration of power and nepotism. A small elite operates these at the expense of the majority of the population and undermines confidence in democracy and the market economy. The BTI 2020 has recorded distorted political and economic competition in a growing number of countries, now numbering over 100. This applies not only to the 63 autocracies, but also to numerous democracies with a weak separation of powers, such as Hungary and Serbia, or with inadequate competition policies, such as Indonesia and the Philippines.

Accordingly, the quality of governance in many developing and transition countries is declining. People in autocratically governed countries are particularly affected by poor governance. Of the 42 very well and well-governed countries, only one is autocratic: Singapore. In contrast, of the 46 countries with poor or failed governance, only five are democracies: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Hungary, Lesotho, Lebanon and Nigeria. Overall, in this decade alone, governance quality fell significantly in 42 countries. These include populous countries with large economies such as Brazil, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria and Turkey. The consensus-building elements of governance, in particular, have deteriorated. Existing ethnic, religious or regional cleavages are often exploited and deepened. A lack of public confidence and inadequate political leadership are poor prerequisites for successful crisis management and the containment of COVID-19.

Glimmers of hope against the authoritarian trend

More repression in autocracies, more deficiencies in democracies: this trend is not irreversible. In Ecuador, an increasingly authoritarian regime was overcome, and democratization processes began in unexpected places such as Armenia and Malaysia. There were also rays of hope against the authoritarian trend in Ethiopia and – after the end of the BTI assessment period – also in Algeria or Sudan. There, prolonged protests have led to changes in government and hope for political change. The results of the BTI 2020 underline that positive impulses for transformation currently come far less frequently from governments than from critical civil societies that are resisting the dismantling of democratic standards.

Background

Since 2004, the Bertelsmann Stiftung's Transformation Index (BTI) has regularly analyzed and evaluated the quality of democracy, market economy and governance in currently 137 developing and transition countries. The assessment is based on over 5,000 pages of detailed country reports produced in cooperation with over 280 experts from leading universities and think tanks in more than 120 countries. The BTI is the only international comparative index that measures the quality of governance with self-assessed data and offers a comprehensive analysis of political management in transformation processes.