Janet Biehl recently presented in London volume 1 of the autobiography by Sakine Cansiz she translated, “My whole life was a struggle” (Pluto Press).

Biehl is currently translating the second volume of Cansiz' autobiography.

She spoke to ANF English service about the role of Cansiz in preparing the ground for new generation of Kurdish women and about what it meant for her to translate this book.

Translating an autobiography is never the same as translating say a novel or an essay. It implies a kind of full immersion in the person’s life. In a way you suffer, are happy, cry and smile with the person whose life you are translating… What did it mean for you to translate Sakine’s autobiography? Did you know her before or did you discover her life while translating the book?

Please allow me provide some background about the book. Sara wrote her memoir in the mountains in 1996-97, under the title [Hep Kavgaydı Yaşamım] My Whole Life Was a Struggle. The book is long, comprising three volumes. The one just published by Pluto Press in April is volume 1, which covers her early life up until her arrest in 1979. Volume 2 is about her time in prison, especially Diyarbakir prison no. 5 during its most notoriously hellish period of 1980-84 and after. Volume 3 must be about her life after her release in 1991, in the Bekaa and in the mountains and in Europe, although I haven’t read it yet…

She wrote the book in Turkish, and it was published in Turkish, and then Agnes von Alvensleben and Anja Flach translated it into German. In April 2015, at a Kurdish conference in Hamburg, I bought the first two German volumes. Then sometime later, when I was in London, I asked Estella Schmid to recommend a history of the PKK. She suggested Sakine’s memoir--which was already on my shelf!

So I started reading it and got immersed. I had trouble putting it down. She writes intimately and with seeming frankness about being born into a place and time where Kurdishness was denied and banned, and also where the prevailing gender system strictly controlled women and prevented them from doing much of anything except childrearing and domestic work. A woman had to go from her father’s house to her husband’s house. There was no place for an unmarried woman, except as a prostitute perhaps. Yet she escaped form these impossible conditions, and by the end of the book, she has transformed herself into a Kurdish militant and an autonomous woman.

Of course, she was brilliant and fiercely committed. She also had some lucky breaks, but she was smart enough to know how to take advantage of them, and in the end she made her own luck and reinvented herself. I should point out that she is also rigorously self critical--throughout volume 1 she keeps saying that her theoretical understanding was not yet good enough. She is learning in these years, and the reader learns through her. That makes it easier for the outsider reader to understand the movement and its goals.

People who knew Sara in real life have told me she was very warm personally, and that comes across in her writing. It’s unusual that someone so fierce and rigorous would also have great personal warmth—such people more often impatient or rude or domineering. But Sara seems to have been emotionally generous, and her warmth comes across in the book. That combination of rigor and warmth was fascinating to me.

In any case, as I read, I realized that the book was good enough to be translated and in fact had to be translated, because Sara was and is so important in the Kurdish freedom movement. It’s a historical document, in addition to a fascinating story. So I had the honor of spending much of 2016-17 translating it.

Sakine led a very intense life. What do you think is the book “message” for women and especially young women today? And especially non-Kurdish women? How do you actually think this book would be met by women in Europe, or the States?

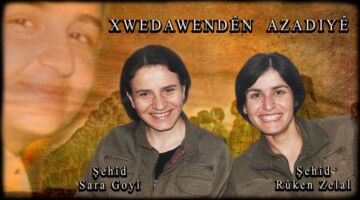

The circumstances from which Sara emerged were desperate. Even women not stuck in a traditional gender system must respect how she escaped it. As a woman and as a Kurdistan revolutionary in the 1970s, Sara was brilliant enough to blaze the trail. She had to carve out her own place in Turkish society, creating her own new circumstances. Today, thanks to her work, and the work of many others, young Kurdish women who want to flee the traditional gender system have a place to go—the movement itself. They can follow in her footsteps. The path is well trodden by now, but it was she who paved the way.

For non-Kurdish women, Sara’s life may have a different kind of importance. She is potentially an eminent person in the history of the international left, in world revolutionary movements. I don’t know whether she is on the scale of Rosa Luxemburg, that has to be evaluated, but at least with the publication of her memoir, others can begin to evaluate her accomplishments. Her incredible resistance, especially in volume 2 in Diyarbakir Prison (I’m translating that volume now), is on a scale that requires the attention of all socialist revolutionaries. Sara modelled how to resist in prison. She deserves to be much better known by socialist revolutionary thinkers and historians globally, and I hope this book will contribute to improving that understanding of her.

It’s also a history of the emergence of the PKK itself because her life overlapped with a large part of the history of the PKK. So reading the book helped me understand both better. She recognized the truth of the Kurdistan Revolutionaries’ objectives right away, when she discovered them around 1975, and becomes their fierce advocate despite leftist criticisms of her as “nationalist.” She recounts how Kurds with inchoate yearnings for freedom came together the PKK at the 1978 founding congress.

But because Sara didn’t write the book for the outside world, I admit, I had to struggle to understand certain things. She mentions certain individuals and political groups and places on the assumption that the reader will know who and what they are. But many English readers will not, any more than I did. Even the context of the Turkish left in the 1970s is unfamiliar to English readers, but I was able to research how the Kurdistan Revolutionaries came out of the Turkish milieu and especially the left. And I drew on histories of the Kurdish movement in English to write explanatory notes and an introduction.

When and how did you come across the Kurdish Liberation Movement?

At first it was through my then partner and collaborator, Murray Bookchin, here in Vermont in the United States. In April 2004 two German solidarity activists contacted Bookchin, suggesting he have aa dialogue with the imprisoned Kurdish leader Abdullah Öcalan, since Öcalan was very interested in Bookchin’s work. This was the first we heard of it. Murray replied that he was glad to hear of Öcalan’s interest. They exchanged compliments, Murray was too sick, tired, and disappointed for a dialogue. Öcalan went on to incorporate Bookchin’s ideas, among others, into Democratic Confederalism, which the PKK accepted sometime around 2005. After Bookchin died in the summer of 2006, the PKK assembly issued a very impressive tribute to him—they promised to build the first society on earth around his ideas.

For several years after Murray died, I was busy writing his biography (published in 2015 as Ecology or Catastrophe: The Life of Murray Bookchin). Meanwhile in 2011 I was invited to Diyarbakir, to participate in the Mesopotamian Social Forum. That conference opened my eyes to the Kurdish movement, and I have been working for it in one way or another ever since—visiting Rojava and writing about it; writing about the Bookchin connection; and translating work by German comrades into English. In 2013 I translated Democratic Autonomy in North Kurdistan and in 2016 Revolution in Rojava by Knapp, Flach, and Ayboga.

The Kurdish people live in many countries, and the Kurdish freedom movement is international. I see it as part of internationalism to translate each other’s work when possible. Personally, I live in a faraway place with few Kurds and little Kurdish activism, few meetings, or demonstrations to participate in. So my form of political practice must be different, more isolated--I make these translations.

Sakine’s book is yet another example of the PKK election of putting women at the center of its political discourse since the beginning of its activity, something quite ‘bold’ and not exactly popular given the context and political environment where the PKK was developing. As Öcalan says, the Kurdish revolution will necessarily pass through a women revolution…

Yes, as early as the 1970s, according to volume 1 of Sara, Öcalan emphasizes that women must participate in the movement. In fact, Sakine seems to have been the first to organize women, creating women’s groups as early as 1975-76 around Dersim and conservative Bingöl.

In those years she was organizing for goals and analyses that the Kurdistan Revolutionaries held at that time. Back then neither the Kurdistan Revolutionaries nor the PKK had any ideological emphasis on women’s liberation, or even a theory of it. The 1978 PKK program just mentions women in passing, as a group among others that needs to be organized. It attached no great importance of women’s liberation, in contrast to today, when the Kurdish movement makes women’s liberation fundamental, insisting that a revolution that does not alter the status of women is no revolution at all.

Anyway, after the 1978 founding congress, when the PKK was brand new, Cemil Bayik gave Sara herself the task of developing a theory of women for the party. She was thrilled and looked forward to the task, to doing research on gender systems in Kurdistan and around the world, and on the nature of women women’s resistance movements in history and in the present. But she didn’t have a chance to do this work because she was arrested in early 1979, which put an end to all her plans.

Now of course things are much different. As I understand it, women’s organizing in the PKK became very intense in 1994-95. And Öcalan asked Sara to write this very memoir then, precisely as an inspiration to younger women. That must have been interesting for her, their foremother. Back in the 1970s, she had had to be clever and persistent and brave to escape the gender system, and her greatest dilemma was that she had no place to flee to—she had to invent her own basis for autonomy. But young women in Kurdistan today who wish to escape the gender system have a place to flee to: the movement itself welcomes them.

The women who fought in the women’s units in the 1990s have become role models for the next generation of Kurdish women. Young people of both sexes appear to me to be familiar with and accepting of women who are independent and outspoken, as well as tough and determined warriors.

Women are the driving force of the Rojava Revolution. Can you comment on that based on your experience?

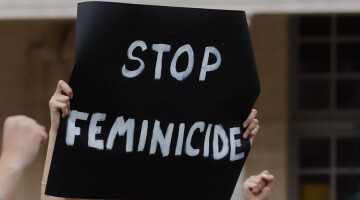

By the time I visited Rojava (as it was then called) in December 2014, the women’s movement in the PKK was already two decades old, and they were ready to implement women’s liberation—they put it front and center. The democratic self-government had banned “honor killings,” marriages under eighteen, forced marriages, violence against women, and polygamy. In cases of rape or other violence, the woman was formerly always blamed; now both sides could be heard, and the man, if found guilty, faced consequences.

The Social Contract, adopted in January 2014, not only banned this old patriarchal system but affirmed positive roles for women: “Women have the right to participate in political, social, economic, cultural spheres and in all areas of life. Women have the right to organize themselves, and eliminate all forms of discrimination on the basis of gender.”

Moreover the new system affirms that women have equal status to men in the eyes of the law. In November 2014 the Cizire self-administration called for “equality between men and women in all spheres of public and private life.” Women run for and hold public office, work for equal pay, They can be trained for and enter any profession.

The democratic self-administrations (DAAs, one in each canton) created women’s committees and centers, places where women can talk about their family and social problems, find legal and economic support. (How Sara could have used that!). Arab and Christian women can find help at women’s centers, as the problems of patriarchy transcend ethnicity and religion. A woman fleeing domestic violence or an unwanted marriage can find safety and support at a center or even at a public meeting, where it can be discussed and investigated. When I was in Qamishlo, I saw an all-women meeting. Most of the participants there were older and wearing headscarves, yet were making use of the lifeline that they and their sisters and daughters had been thrown and were looking toward a brave and liberated future.

At the women’s centers, women can learn new skills so they can support themselves without relying on male relatives. The women’s center in Qamishlo offered a popular course on “women and rights,” teaching women that they really do have the right and the ability to conduct their own lives based on their own choices. In economic life, the DAAs have created women’s cooperatives, to help them achieve financial independence while building a noncapitalist economy.

The DAAs sought to eliminate the thousands-of-years-old patriarchal mindset by establishing women’s academies. These academies teach students of all ages that transforming the status of women transforms the whole society; and that women are primary actors in economy, society, and history. Even the academies that train the defense and security forces teach such ideas.

The YPJ was established in 2013, when some of the women in the YPG (founded in2006) wanted an all woman force. During the defense of Kobanê, the women of the YPJ became internationally famous, for their commitment and fearlessness. They are fighting not merely for the survival of Rojava but for the liberatory system of self-government that they helped create, and for the future of the Middle East and all humanity.

Above all, women in Rojava participate in public and political life. All leadership positions, in every institution or organization, are twofold: one male and one female. And any meeting must consist of at least 40 percent women to have legitimacy. This quorum is observed in the mixed-gender people’s councils, organizations, and committees. Alongside the mixed-gender councils are corresponding all-women councils that have veto power over decisions that affect women.

As a result of all these innovations, women in northern Syria have become a real force, playing leading roles in politics, diplomacy, social issues, and defense, as well as in building a new family structure. Patriarchal traditions are deeply embedded in northern Syria and are often bound up with religion. For a unknown number of women, liberation still lies in the future. But the promise of rescuing women from these oppressions is very powerful.