Mûna Beşîr Xelîl, Yasmîn Silêman and Mîdiya Eslan Deqorî are three Kurdish women in northeast Syria. Each of them has a different life story, but a common fate brings them together: War and terror have been raging in parts of Syria for ten years. The conflict has produced an indescribable humanitarian catastrophe, an almost unimaginable tragedy that Mûna, Yasmîn and Mîdiya also witnessed from the beginning. Today, these three women share not only memories of the past, but a common goal: to dispose of the explosive hazards of the jihadists from the self-proclaimed ISIS, the mines and rigged explosives. Their vison: risking lives to save lives.

ITF in Rojava for two months

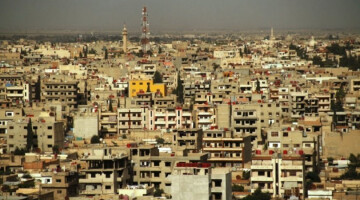

The ITF (Enhancing Human Security, previously named International Trust Fund for Demining and Mine Victims Assistance) was established 23 years ago on the initiative of the Slovenian government. The ITF was to take care of mine clearance on the territory of the former Yugoslavia, especially in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as agreed in the Dayton Peace Agreement. To date, ITF specialists have also been deployed in Afghanistan, Albania, Israel, Gaza, Kyrgyzstan, Colombia, Libya, Ukraine and a number of West African countries. In the process, hundreds of millions of square kilometers of contaminated land have been cleared of deadly booby traps. For the past two months, a team from the civil society organization has been in the autonomous region of northern and eastern Syria. Their work is focused on the greater Hesekê area. Mûna, Yasmîn and Mîdiya are also working there. Necah Meîş from the NuJINHA women's news agency accompanied them.

Mûna in search for mines

Mûna in search for mines

Systematic contamination by ISIS

Mûna Beşîr Xelîl is only 22 years old. In the meantime, two years have passed since the mother of two began working as a deminer. Before that, she went through an intensive training phase. When asked why she decided to take on this dangerous job, Mûna says: "The ISIS systematically mined places during its retreat to prevent displaced people from resettling. Many people lost their lives as a result, especially children. Survivors are still badly scarred today. I just don't want more people to die."

The minesweepers of Hesekê

The minesweepers of Hesekê

Mûna's colleague of the same age, Yasmîn Silêman, lost a brother in the fight against ISIS in 2015. For the past three years, she has been involved in various demining projects within the self-governance structures. "Certainly, it is dangerous to remove the dangerous legacies of ISIS. But it is ultimately the safe future of all of us that is at stake here," she says. Yasmîn is happy to be part of the squad. "What I like most is the fact that we work in an environment free of discrimination and sexism, and gender equality is not overlooked."

Yasmîn Silêman

Yasmîn Silêman

Places where children grow up happily

In the area where she works, a boy stepped on a mine some time ago and lost both legs. "That's why our work is especially important. Imagine if we cleared this land of mines and then handed it over to its owners. The land could be optimally cultivated again and grant people a livelihood. Or it could be turned into a school, a place to educate children who are happy. Isn't it worth it?" asks Yasmîn.

Until recently, Mîdiya Eslan Deqorî lived in Til Temir, a predominantly Christian town in the flat valley of the Xabûr (Khabur). She lost her husband in the Turkish jihadist invasion in October 2019. She then moved to Hesekê with her two children. "I don't just want to dream of a future where there is peace and tranquility and my children can grow up carefree. I want to shape it myself," says Mîdiya. She is well aware of the risk involved in her work, she says and adds: "But I've gotten used to the potential danger. I'm just doing my job to provide a service to the peoples of my homeland. After all, we are not only removing the remains from ISIS, but creating new and safe habitats. That's what matters."

Mûna in search for mines

Mûna in search for mines The minesweepers of Hesekê

The minesweepers of Hesekê Yasmîn Silêman

Yasmîn Silêman