A century-old issue and a path to resolution

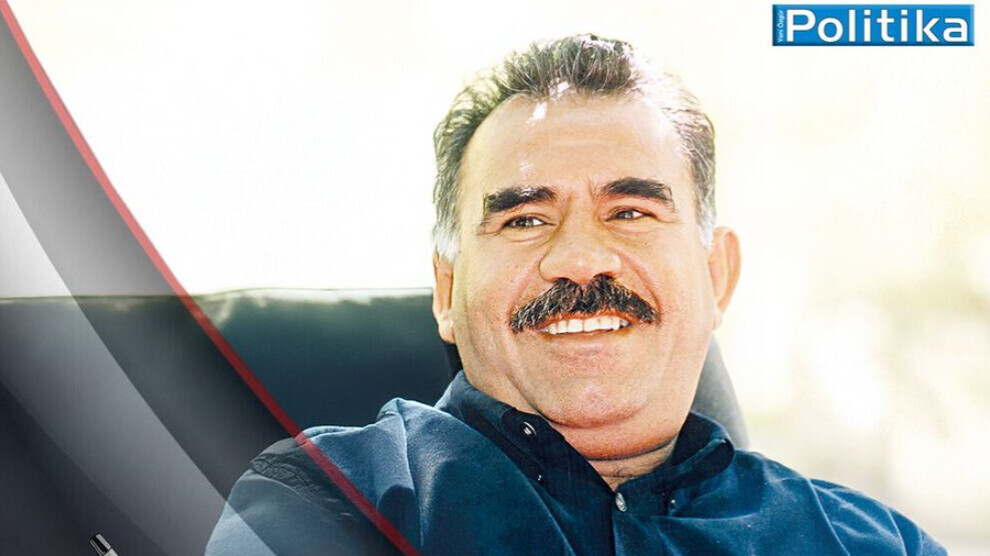

Abdullah Öcalan’s project for democratization through Kurdish freedom offers Turkey a historic opportunity.

Abdullah Öcalan’s project for democratization through Kurdish freedom offers Turkey a historic opportunity.

June 29 marks the one-hundredth anniversary of the execution of Kurdish resistance leader Sheikh Said and his companions in Amed (Diyarbakır) in 1925. Commemorations are especially strong this year, as the centenary brings renewed attention to a brutal historical injustice. Even after a century, the burial places of Sheikh Said and his comrades remain unknown. For those who ask, “What is the Kurdish question?”, here are two answers: execution and the denial of a grave.

It is well known that Sheikh Said and his companions resisted the Turkish Republic’s 1924 Constitution and the Treaty of Lausanne, both of which denied the existence of the Kurdish people and laid the foundations for their erasure. Their resistance was a stand for Kurdish existence and freedom. They demanded the application of the principle of “the right of nations to self-determination,” a principle widely accepted at the time by both socialist and capitalist blocs. It had been articulated by Vladimir Lenin on the left and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson on the right. The League of Nations, predecessor to the United Nations, also recognized this right.

Moreover, Kurdish–Turkish relations date back to the arrival of Turkic tribes in the Middle East. Kurds played a pivotal role in the Seljuk victory at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071. Their support was equally vital in the Ottoman Empire’s expansion into the Middle East. Within the Ottoman administration, Kurdish principalities enjoyed a distinct form of autonomy.

When the Ottoman Empire collapsed after World War I and the search began for a new state, Mustafa Kemal launched his initiative from Kurdistan, beginning with the Erzurum and Sivas congresses. The National Pact (Misak-ı Milli), drafted from Amasya to Erzurum, defined the homeland as “the lands inhabited by Turks and Kurds.” When the Grand National Assembly opened in Ankara on April 23, 1920, nearly half of its delegates were Kurdish. In what came to be called the “War of Independence,” it was the Kurdish people who fought against British and French colonial forces. The Assembly’s 1921 Constitution even included provisions for Kurdish autonomy. At that time, the Ankara government described itself as a joint administration of Turks and Kurds.

The first major rupture came with the Treaty of Lausanne, signed on July 24, 1923. At Lausanne, the Kemalist movement struck an agreement with its former enemies, Britain and France, and turned against its former ally, the Soviet Union. In doing so, it also accepted the exclusion of the Kurdish people’s rights from the treaty. It appears that Britain and France agreed to the proclamation of the Republic of Turkey on October 29, 1923, on the condition that the new state would both sever ties with the Soviets and deny any recognition of Kurdish rights. With the backing of these victorious colonial powers, the Republic of Turkey drafted a new constitution in 1924, abandoning its prior political framework and formally codifying the denial of the Kurdish people. From that moment on, the state set out to eliminate Kurdish existence entirely. This is how the “Kurdish question” was born, as a mentality and policy of denial and annihilation.

The uprising led by Sheikh Said in February 1925 was the Kurdish people’s first major response to this policy of erasure. The century-long Kurdish question and the resistance movement for Kurdish existence and freedom developed out of this foundation. In turn, the Republic of Turkey’s consistent response to Kurdish resistance has been one of suppression and execution. For the past hundred years, this vicious cycle of rebellion and annihilation has continued in lockstep.

Yet Sheikh Said and his comrades were neither opposed to Turks nor to the republic itself. Their resistance was in response to broken promises. Since the Erzurum and Sivas congresses, the Turkish nationalist movement had promised Kurds autonomy, promises later ignored in both the Treaty of Lausanne and the 1924 Constitution. Sheikh Said and his companions demanded the realization of this autonomy, which had been declared by Mustafa Kemal himself.

The same demands persisted in the years that followed, and there was hardly a Kurdish city or town that did not rise up in resistance. After the Amed –Bingöl uprising in 1925, the Serhat (northeastern) region rose up in the 1930s. In 1937–1938, Dersim (Tunceli) became the site of yet another rebellion and genocide. Seyit Riza, the leader of the Dersim resistance, was invited by the state to Erzincan for negotiations. Upon attending, he was arrested and executed in Elazig (Xarpêt). To this day, the burial sites of Seyit Riza and his companions remain unknown.

On the fiftieth anniversary of this policy of denial and annihilation, Abdullah Öcalan, the Kurdish people's leader, launched a new resistance for existence and freedom with the Çubuk Dam meeting. This resistance, developed with modern consciousness, organization, strategy, and tactics, could not be crushed by the Republic of Turkey as easily or quickly as it had done in previous eras. As a result, the Turkish state turned to its historical allies in the Kurdish genocide, regional and international powers, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Eventually, an international conspiracy led by the United States (US), the United Kingdom (UK), and Israel resulted in the abduction of Abdullah Öcalan on February 15, 1999, from Kenya. He was imprisoned in the Imrali system of isolation, torture, and annihilation. In a grim historical echo of the first Kurdish resistance, Mr. Öcalan was sentenced to death by the Imrali court on June 29, the same date Sheikh Said and his comrades were executed. Today marks the 26th anniversary of that sentence.

The Kurdish people's leader, Abdullah Öcalan, not only sustained his resistance against the policies of denial and annihilation but also endured through the death sentence and the Imrali isolation system. As we now mark the 26th and 27th years of that resistance, and as the Kurdish question itself reaches its hundredth year, new and significant opportunities for resolution have emerged. In October 2024, when Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) Chairperson and government ally Devlet Bahçeli issued a “call for a solution,” Mr. Öcalan responded positively and presented a concrete “Solution Project.” This development created a serious and historic chance to resolve what has long been Turkey’s most fundamental issue: the Kurdish question.

The primary reason such an opportunity has emerged lies in the fact that the resistance led by Mr. Öcalan, now over fifty years strong, has not been crushed or dissolved by the Turkish state as earlier Kurdish movements were. The ongoing conflict has imposed an immense burden on both Turkish society and the state itself. The second reason is the level reached by the Third World War unfolding in the Middle East since the 1990s. For a Turkey that has failed to resolve the Kurdish question, the growing regional conflict presents a severe threat. Devlet Bahçeli has referred to this as a “state survival crisis.” The war between Israel and Iran, now in its tenth day, along with the direct involvement of the United States and the broader goals of the conflict, affirm Bahçeli’s diagnosis of an existential threat.

At this moment of profound crisis for the Republic of Turkey, the project and roadmap proposed by Abdullah Öcalan, democratization grounded in Kurdish freedom, presents an invaluable opportunity. Clearly, a Turkey that resolves the Kurdish question and undergoes democratic transformation on this basis will leave no ground for foreign intervention. A democratized and unified Turkey can not only neutralize all forms of attack but also offer a new democratic model for the Middle East.

However, instead of recognizing this historic moment and embracing Mr. Öcalan’s solution project, some have adopted evasive, dismissive, and delaying attitudes. Worse, there are efforts to launch defamation campaigns against Mr. Öcalan. Let it be known to all: no one can cover the sun with mud! Any slander thrown at Mr. Öcalan will only stick to those who hurl it, darkening their own hands and faces.

With the hope that everyone will correctly assess the past hundred years and clearly recognize the current opportunity for resolution, I respectfully commemorate all the martyrs of Kurdistan on the hundredth anniversary of the execution of Sheikh Said and his comrades.