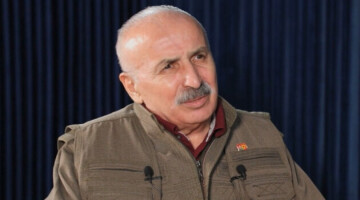

Mustafa Karasu, member of the KCK (Kurdistan Communities Union) Executive Council, spoke about the historically important occurrences in the month of March, the development of Abdullah Öcalan into a people's leader, and the current developments in Turkey with regard to the Kurdish question. Karasu also gives an insight into how the Kurdish freedom movement approaches the current discussions and what perspective it is pursuing.

We publish the first part of the in-depth interview broadcast on Medya Haber TV below:

To get straight into our conversation, we would first like to take a look at the past few weeks. March in particular is a month of great significance for your movement. Historically, this month has seen critical developments for Kurdistan, and within it, many important people have given their lives for the freedom struggle. Last but not least, Newroz and the week from the 21st to the 28th, which your movement calls ‘Heroism Week’, are also part of March. What significance and impact do these developments still have today?

In the past month, some precious people, such as Mother Sakine (Sakine Arat), one of our precious mothers who fulfilled an important role in our struggle, and Heci Ehmedi, one of the founders of PJAK, who has an important place in the freedom struggle of Eastern Kurdistan, as well as all four parts of Kurdistan, have become martyrs. Both have made significant contributions to this struggle and will always be remembered.

On this occasion, and since it is the month of Newroz, I also want to gratefully and respectfully remember our modern-day Kawa comrade Mazlum Dogan, as well as the comrades Zekiye Alkan, Rahshan Demirel, Ronahi, and Berivan, whose struggle has made Newroz what it is today.

As you mentioned, March 21-28 was also the Heroism Week, and in this context, I would also like to commemorate comrade Mahsum Korkmaz. Mahsum Korkmaz’s place in this struggle is well known. His stance and attitude played a very decisive role in the mobilization of the people, in the initiation and development of the armed struggle. We will always remember him as people and keep him alive in our struggle.

I also want to take the opportunity to respectfully commemorate three martyrs of the early stage of our struggle, who gave their lives on March 28, 1980, in Shikestun, Merdin (tr. Yaykili, Mardin); Mehmet Kurt, Ahmet Kurt, and Salman Dogru. They were some of the most important militants at the beginning of our struggle. They were really valuable comrades. We were in prison when they were martyred.

Then, I want to gratefully and respectfully commemorate Abdurrahman Timoki, who was also martyred this month. He was a valuable person, a man of religion, a man of faith, and in his last years he became an Apoist. He had joined the PKK because he found all the positive values that he searched for in the religion he believed in, in Islam, in our party. He saw that our party kept alive the real moral, conscientious, and social values that he believed in. He became a true Apoist. So much so that at that age, after joining the party, he did community work in Aleppo. Maybe this is little known, but he did public work in Aleppo as part of a committee assigned by Rêber Apo [Leader Abdullah Öcalan] himself. Because he saw the development of the PKK’s struggle as the realization of his own goals and values. He remained committed to this movement until his last breath. I remember him with gratitude and respect.

The month of March also brought along even more historically significant developments. Like the execution and martyrdom of the leaders of the Mahabad Republic, Qazi Muhammad and his friends, in Eastern Kurdistan after its collapse. I also commemorate them with gratitude. They too have a very important and prominent place in the memory of the freedom-struggling Kurdish people. They played a great role in the continuation of the Kurdish uprising and in the revival of the Kurdish passion for freedom. They have also made a great contribution to today’s struggle, which can be seen as a response to their legacy, as the PKK is the continuation of the struggle of the martyrs who gave their lives for a free Kurdistan. The PKK keeps their memories and struggles alive. It was like this in the past, it is like this in the present, and it will be like this in the future.

Of course, there are many other martyrs we need to commemorate. There is for example the martyrdom of Mahir Cayan and his friends on March 30, 1972 in Kizildere. Mahir Cayan is a very important leader of the revolutionary movement in Turkey. If there is a leftist tradition, a revolutionary spirit in Turkey today, then Mahir Cayan’s thoughts and practice have had a very important impact in creating, sustaining and carrying this tradition until today. Rêber Apo is big a sympathizer of Mahir Cayan. In fact, when Mahir Cayan was murdered in Kizildere, Rêber Apo led the boycott at the Faculty of Political Sciences, the university where Mahir Cayan had studied. He was young then, just a freshman. He was not in any organization, just a revolutionary sympathizer, a sympathizer of Mahir Cayan. Because of this leadership he was imprisoned for about seven months. It was in this period when Deniz, Yusuf and Huseyin were executed. The struggle and resistance of Mahir Cayan had an impact on our struggle, and they still are alive in our struggle. I also want to remember them with gratitude and respect.

Something else drastic also happened a few years ago in the month of March. It was in Mush where 14 of our guerrilla fighters had been brutally massacred with chemical weapons. This created a great outrage and anger in Amed (tr. Diyarbakir) and all of Kurdistan. The uprisings that followed this month in Amed were some of the most important actions in the history of Kurdistan. The spirit of resistance, the militancy, the patriotism, and the general will to struggle of the people of Kurdistan were clearly seen. That month, Amed recreated itself once again. In fact, throughout our 50 years of struggle, the people of Kurdistan have been constantly recreating themselves. The spirit of Amed is the spirit of Kurdistan. Amed’s resistance is the resistance of Kurdistan. Amed’s measures of patriotism and struggle also express the measures of patriotism and struggle of all Kurdistan. It raised not only its own standards of struggle, patriotism, and resistance, but also the standards of patriotism, struggle, and resistance of the entire Kurdistan people. On the occasion of this month, while commemorating those 14 comrades with gratitude and respect, I salute once again the people of Amed who stood up.

Can you elaborate on the meaning of these martyrdoms? In particular, with regard to the beginning of this movement and the role that people’s leader Abdullah Ocalan also played in this beginning? And also what this led to?

We have just passed the Heroism Week. Of course, this is a symbolic week, but looking at today’s reality all the guerrilla fighters have become heroes, the whole people have become heroes. This is the result of 50 years of struggle. And it was the great sacrifice of Rêber Apo who created the beginning. In those conditions when Kurdishness and Kurdistan were almost forgotten and made to be forgotten, when fighting for Kurds and Kurdistan was considered the biggest crime, Rêber Apo took the risk and started the struggle and showed a great example of sacrifice. This is how it should be understood. In fact, when Rêber Apo said, “Kurdistan is a colony,” he was almost whispering at the time. Because the emergence of a new, radical organization, an organization that would change the fate of Kurdistan, meant the greatest enmity, the greatest danger for the Turkish state. Rêber dared to do this.

That is the way on how Rêber Apo’s steps in those years should be evaluated. At that time, the Turkish left was influential, particularly among the youth. There were also some groups among the Kurdish youth, groups like Rizgari or DDKD; they were mostly reformist nationalists or collaborationist nationalists. In this environment, forming a separate group needed courage, and it was a very difficult but important step. From the very first day, the group was both excluded by the leftist forces in Turkey and perceived as the other and despised by Kurdish groups. When the group first emerged, both a significant part of the Turkish left and some Kurdish groups were ridiculing it, saying, “Apo has taken 15-20 people with him and is going to establish Kurdistan”. They were belittling and laughing. Back then, Rêber Apo stated: “The revolution in Kurdistan is not easy; it is difficult. If we are going to develop as a group, if we are going to carry out this struggle, we will have to face these difficulties. Everyone must be ready to take the upcoming risks”. In other words, he did not fantasize about the ease of the revolution. He was very clear and told us that the conditions are as difficult as they get, that there are no prepared opportunities that we can simply grab for, and that we are in a period of great chaos, with a harsh geography and a cruel enemy. In fact, when describing the reality of the society of Kurdistan at that time, in order to show how deep the colonial domination was, in order to reflect how sensitive society was, he used the expression “There is almost no Kurd left who has not betrayed himself”. When he said this, he meant that there is hardly a personality, a thought, or a stance that can show will and dare to put up a serious struggle against this genocidal colonialism. It was clear that nothing could be reached just through some words, phrases, and slogans.

Rêber Apo analyzed the absence of such a thought and feeling, the lack of such an understanding of resistance, and the absence of such an attitude. Of course, there still was the Kurdish, but there was no willful stance that could prevent and stop the genocidal and colonialist policies of the Turkish state. At that time, there was a social reality that was struggling in a genocidal-colonialist siege. From such a social reality, a sacrificial army emerged, a sacrificial people emerged. How was this possible? Rêber Apo criticized the Kurdish people, revealing their shortcomings and inadequacies. And of course, while criticizing the Kurds, he also criticized himself. He always said that the personality in Kurdistan had not yet been created and that this would only be possible at all through struggle. This approach gave birth to the self-sacrificial militancy and mentality.

Rêber Apo has a deep-rooted patriotism and a deep-rooted passion for freedom. With these, and with his approach, he was able to unleash the strongest anger in the people against the genocidal colonialism raging in Kurdistan. Through this, he was able to create this self-sacrificial militancy and mentality and this great people’s resistance. Because if you don’t feel the oppression and pressure exerted on you deeply, if your anger doesn’t come out, if you can’t grasp its depth, you can’t put up a great struggle. This is one of the most important effects of Rêber Apo. He creates this kind of anger, consciousness, and passion for freedom in everyone, regardless of who. Just as Kemal Pir said, “I love life so much that I would die for it,” Rêber Apo set forth a goal, a life that people are ready to make sacrifices for. It is Rêber Apo’s sacrificial personality that, for example, made at all possible the death fast of July 14th in the prison. It is the spirit of Rêber Apo. It is the anger, the spirit of struggle, the passion for freedom that Rêber Apo has created against the genocidal colonialists, which has revealed this dimension of resistance in the prison.

For more than 50 years, Rêber Apo has been pioneering this and thus paved the way for hundreds and thousands of militants from Mazlum to Mahsum, from Asya to Rojger. All of these have arisen from Rêber Apo’s passion for freedom, the depth and consciousness created by his commitment to the cause, and the emergence of this in society and cadres.