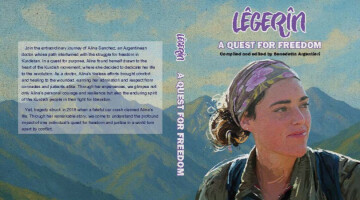

Xeysa Nas' life began in a village near the district of Idil in the Kurdish province of Şirnak. Because of persecution by the Turkish state, she had to flee to Germany in the 1990s. Since her first day in exile, she has been committed to the liberation struggle. In an interview with ANF, she talked about her activities in the Kurdish association Mala Kurda in Bremen and in the Commission for Families of Martyrs. The mother also talked about her daughter Rojda Nas. The PKK fighter, whose nom de guerre was Rûken Hespist, was martyred in Botan in 2007 along with seven other guerrillas.

Could you please introduce yourself?

I come from Şirnak. Our village is called Hespist and belongs to the İdil district. I was born, raised and married there. It is the village of my ancestors.

How old were you when you had to leave the village?

I was 34 years old when I came here. Only one of my children was born here. All the other children were born in the homeland.

What was your life like in the village?

Our village was really beautiful. We were all close to each other, there were no strangers among us. We had a good life then. No one treated the other unfairly. We were engaged in agriculture. There was a beautiful stream next to our village. We had fish, we had rice. We didn't have to buy anything from the city - peppers, aubergines, tomatoes, rice, and so on. We had everything. Our valley was very beautiful.

Then the state came and said: "You are no longer allowed to grow peppers and tomatoes. PKK members come to the valley and use the vegetables. That's why they don't starve. You are also not allowed to plant rice anymore." They forbade us to cultivate the valley, so we could not use it anymore.

Then the revolutionary struggle arose. Some called them "bandits", others "students". I don't remember exactly, but they were called different names. Some denigrated them by saying, "They are thieves who broke into our houses." Only when people came into contact with them did they understand that they were pursuing the same cause as Şêx Seîd. Gradually, we began to understand them.

How did you feel when you saw the guerrillas for the first time? How did you see them?

I will tell you something, but you will probably laugh. I prepared food for them, and they took it. Then they brought me their shoes. I didn't know them, "Oh, are they really human shoes?" I smelled them and said, "By God, they smell human!" They told me nothing. They just asked me to prepare food, but didn't tell me who they would take it to. So, I cooked the meal. Sometimes they brought me old and new shoes. They said that we could work with the old shoes. Some shoes had holes. At the beginning, I didn't know the guerrillas, but little by little we got to know them.

Sometimes they met with us, held meetings and taught us. They explained to us that we would become millions. Sometimes they asked for help. They gathered us in the school and said, "We are your children, you are our parents. We struggle for you. We do not accept the oppression you experience." Our bond became so strong that we wanted to share everything we had with them. Our love for them had grown so strong. We often wondered when they would come and be our guests and what we could do for them.

"As we got to know them, we also got to know the oppression of the state"

We got to know the guerrillas through their beauty. As we got to know them, we also got to know the oppression of the state. The state accused us of taking them in, giving them food and helping them. Then, the military stormed our houses every day. The pressure was not limited to our village, but also reached Filê, Bafê and all the surrounding villages.

Our village is located on the Botan side at the junction of the road to Torî. Everyone from the surrounding villages travelled to İdil via our village. The roads to Botan and Bagok also passed through our village. For this reason, the villages of Bafê, Acaniyê and Filê were also subjected to repression. The people there were patriots like us. They loved the party like us. The guerrillas were our own children. How could we not love our own children? We still love them today. They took to the mountains for us. Wouldn’t they also want to have their own homes and their own children? But their parents are oppressed. Their brothers and sisters are oppressed. Their children are subjected to oppression. Of course, they had to go to the mountains. They didn't go because they were bored. Nobody goes there just like that.

"If it weren't for the Mala Kurda, I would suffocate"

You came to Germany after the attacks by the state. By what route? What did you experience here?

We came here because we were persecuted. If there had been no persecution, it would have been nice in our village. It was our country, our village, we had everything there. When the wall of a house collapsed, the villagers would come together within half an hour and rebuild it. When we built a house, we helped each other. We would never want to leave our land. Who would want to leave their country anyway? But we were oppressed. We had to leave. We were settled in a refugee camp. Three or four times we were taken to other places until we finally arrived here. We experienced a lot of humiliation, we also had difficulties in the refugee camp.

My daughter had arrived here before us. I came later. My daughter and I suffered a lot for a year. I said, "My daughter, I am also very sad." She said, "Mum, we go to the kitchen, but we don't speak the language. We try to speak, but we don't know what language they speak. I want to go back home." I said, "My daughter, look, they say conditions will improve after a year."

I came here and asked: "Isn't there an association here? Isn't there a Kurdish house where you can at least get some air and see some compatriots?" Then I found out that my brother and his friends were active in the organisation there. They were preparing an evening event. When I saw that the association was full of people, I felt relieved and said to myself, "Thank God!" When we came to the association and saw our patriotic people, we told each other about our problems. That's how we gradually got to know our association. We got to know Mala Kurda and it became our home. I have lived here for 27 years, and my children for 30 years. They came two to three years before me. I have not seen my country for 27 years. Without the Mala Kurda, I would suffocate in a day. Because the Mala Kurda embodies our language, our culture, our existence. At least we can talk about our problems together there. Twelve years ago, we, four or five people, including friend Herbijî [Celal Özkan] who is the father of three martyrs, founded the Bremen Commission for Families of Martyrs.

Why did you establish this commission?

We had an urgent need. There are many people like us whose hearts are on fire with pain. We visit them. We live in exile. No one would listen to our problems. Who should we tell our problems to? Germans, Arabs, Persians? No. We can only tell each other our problems. In other words, we visit these families and ask if they have any wishes, how we can help them, what they need. That is why this commission was established. A commission was set up in each town. These commissions meet once a year and they all report on their work. The Commission for Families of Martyrs works officially. It is officially recognised. It is not an illegal activity. It is a commission set up by mothers whose hearts are on fire.

Could you tell us a little about your relationship with the association? What was it like when you first joined it? How did your relationship develop?

In our country, we were so patriotic that when friends taught us, they would say, "When Kurdistan is established, this village will be its capital." We were so happy! So, we worked harder.

When I came to Germany, I went to the association. When I saw a map of Kurdistan there, Hespist was not marked. I asked, "Where is the picture of Hespist?" They said, "Who knows Hespist?" I said, "How, so you don't know Hespist! Hespist is the capital of Kurdistan." We started working with the people. We made jokes. What had we seen so far but Hespist? At most, we got as far as İdil and then returned to our village. We had never seen anything else.

"I taught my children the mother tongue first"

Can you tell about your children? How many children do you have?

I have four sons and four daughters here. One of them fell as a martyr. My children work here. When we came here, thank God there was the Mala Kurda. We took our children there and brought them up. They grew up with their parents' culture. They grew up with their mother tongue. They speak three languages now. Of course, they could have learned Turkish as well. But I forbade them to speak Turkish. I didn't want them to speak that language because Turkey had persecuted us so much. Then, when my children went home, they needed an interpreter. When they went to the consulate, they were told, "Why don't you speak Turkish?" They grew up here. Their mother didn't speak Turkish, neither did their father. What can we do? We don't speak Turkish.

The mother tongue must come first. I brought up all my children in their mother tongue. My child who was born here speaks Kurdish very well. Sometimes he confuses the words, but thank God he is good at the language. I thank God that our children grew up with the culture of their mother, their ancestors and their homeland.

"My daughter was worthy of the mountains"

Let's talk about your fallen daughter.... What was Martyr Rojda's childhood like?

I can't put her childhood into words. She left with dignity. We were not worthy of her. She was very active in the country. She used to say, "Look, Mama, when the comrades come, I will bring them food." Even when she was hungry, she would think of the comrades first. She would try to bring them a plate of food. I said, "This plate is not enough for you, why are you giving it away?" She replied, "No, I am not hungry." She loved the comrades so much!

When she came here, she was very sad. She became sadder and sadder and was only a shadow of her former self. Sometimes I told myself that it would get better after two years. But she always said, "I can't breathe here." She went to school here for one year. She never left the house. She went to school and came back, but didn't leave the house. She knew German. She listened to Kurdish music on a tape recorder all the time. She did that for a while. Then she got the idea of returning to the country. She always said, "I'm not going to stay here. I won't stay here even if you kill me."

One day, after breakfast, she said, "Mum, you can watch TV, I'll clean the dishes." She always did that. She did everything by herself and organised the household. Our guests would come, and she would clean up everywhere. She was such a humble, hardworking person. She deserved that place. I congratulate her for falling a martyr for this revolution. No misfortune has befallen her.

Then she was gone... That morning I looked, and the plates were still there. A friend had come to our house. Rojda told her to spend the night with us. The next morning, I found that my daughter had disappeared. We asked everywhere where Rojda was. Her code name was Rûken, her name at home was Rojda. We asked where Rojda had gone. She had a friend who said, "Someone called a taxi and your daughter Rojda got in and left." I looked and saw that her other friend was not there either. I understood and said to myself, "Ok, they've gone."

No matter what we say, it's about the heart. It was the time when Rêber Apo (Leader Abdullah Öcalan) came to Italy. Rojda was in education there. When she disappeared, we didn't know where she had gone. The police asked us what we wanted. We said, "She is of age, but we don't know where she went." They asked us if she had joined the PKK. "We don't know," we said. "Do you want to file a complaint?" they asked. We declined. Of course, I had learned by then that she had left. More than six months had passed. Then a person called, "She got sick at work, we'll take her home." We said, okay, bring her home. Our daughter came home. We took her to the doctor. The doctor said her blood value was bad. She stayed with us for a month. When she got better, she said, "Mum, I'm going to go." I said, "You were there, you saw them, they have no clothes, they live on the mountain without shoes, where are you going? You can't bear it like them." But she said, "No, Mama, I'm going."

When my daughter said she was going, her father and I bought clothes and a phone card for her. We asked, "Are you really going?" She said, "Yes." We accompanied her to the bus stop and said goodbye. In the beginning, we had difficulties, but we saw her off ourselves.

Five or six months after she left, I received a phone call. I picked up the phone and asked if it was her. She answered, "Yes, mum, it's me." Then she said, "I have reached you now. Talk to your mother, you may not have a chance to talk to her again, the friends said." I said, "Look, my daughter Rojda. You have gone to them and settled down. But if you are wounded, blow yourself up, but do not surrender to the enemy. If you surrender to the enemy and testify against your comrades, my sin will be on you." She agreed and we promised to think of each other.

Once we received a letter from her. She wrote: "Send me a camera." We sent her a camera. We sent many things, but they did not reach her. She was in Qandil. We received a photo of her. And then she sent a letter. She wrote that she was going to Botan and needed clothes. I sent her clothes. She took a photo with the dress and sent it to me. After that I did not see my daughter again. She did not call me, and I did not call her.

One morning, her father woke up and said, "We will organise a condolence service." I asked him why, what kind of a funeral service? He said, "I will organise a condolence service for my daughter." When I asked him why, he said, "Your daughter was martyred, and her body is lying on the ground right now." Then he said he had dreamt that she had been hit by a bullet, she was just paralysed. Doctor Mahir was her doctor, he said. This doctor also fell with her. I didn't believe all that and said: "Listen, acquaintances said that she had come to Southern Kurdistan. She was in Botan and is back in South Kurdistan."

Afterwards, we went to the association. The commemoration of Comrade Zîlan was going on there. I said, look, we have eight martyrs. Orhan Doğan had a heart attack. The bodies of the martyrs were still on the ground on the video on the news. It turned out that there were subtitles on TV and my daughter's name could also be read. I myself am illiterate. I said turn up the TV, there is a news programme. They said they wouldn't do that. They knew. They had read the subtitles. Then they turned on the TV and the second news bulletin said, "Rûken and seven friends have fallen in Uludere."

"Not a tear will flow from my eyes"

There were maybe 60 or 70 people present. I cried out, "My daughter Rojda, my Rûken!" I had sworn not to shed a tear unless she testified against her comrades and fell. But the heart... What can we do? I turned to my friends again and said, "I apologise to you. My daughter fell with dignity, she did not surrender. She resisted till the end. I congratulate the guerrillas, Serok Apo and our patriotic people for her martyrdom." Tears welled up in my eyes. We got up together and went back home. Her father told me that he had not been able to tell me directly that our daughter had fallen. Then we prepared the funeral service.

They said, "Get a Turkish passport and travel there to attend your daughter's funeral." I refused. An older sister of hers was there. The other children had already left when they heard about it. I don't mean just our family. Thousands of people marched behind her all the way to Hespist. I said, "Am I her only mother? All those who marched behind her are her mothers. They are all as heartbroken as I am. Our martyr is not alone, our children are not alone."

"The state fears even the bones of the martyrs"

Since that day, I have continued her struggle. I promised her: "My daughter, do not look back. As long as your mother lives - and I say this on behalf of my siblings, children and relatives - we will continue your struggle. We will not betray our people. We will not betray our martyrs. That is all I am saying." Since then, I have been working tirelessly to continue Rojda's struggle in any way I can. I am part of Rojda's struggle. (She points to the newspaper photo.) Eight comrades fell together. You see, one of them was captured alive. Who captured him and killed him? Where is he? I will follow their cause. We want to know who killed him. We will do whatever is in our power. Thousands of her brothers and sisters continue Rojda's struggle. They have not given up their weapons. Why do we say "Şehîd Namirin" (Martyrs are immortal)? Because the place of the martyrs is always being reoccupied. The Kurds are spread all over Europe. They all have children. They are all part of this struggle. We are persecuted, oppressed. Our home was burnt down, our houses destroyed. After six years, I told the children to prepare a grave in the village, even if only bones are left. They went, built a coffin and brought her remains to the village to bury them. In total, we have six or seven martyrs. Even these graveyards have been destroyed by the state. We are not even allowed to bury our dead. I ask myself, how far can injustice go? The state is even afraid of the bones of our martyrs.

22,500 signatures collected for the freedom of Abdullah Öcalan

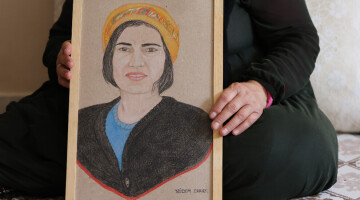

Here are some photos. There is a photo of Abdullah Ocalan and photos of Rojda at different times. Can you tell us more about them?

When there was a signature campaign for Rêber Apo, we also collected signatures. We went to the association and suggested collecting signatures together in one street. At first, we put the completed lists in one place. Then when the friends saw how many signatures I had collected, they said, "You are really doing a lot." They suggested that I keep my signatures separately.

I wanted to collect signatures. But we have enemies here too. There are many who hate us here too. I cooked dinner for my children and then I collected signatures instead of sleeping. It became a kind of school for me. I was on my way to the Bremen train station and knew a few German words. Some people took the sheet I gave them and tore it up. Some Germans made victory signs and rejoiced.

One day a friend from the association said to me: "Comrade Xeysa, the police asked me why we weren't at the signature stand for Rêber Apo." Imagine a police officer commenting on the incompleteness of our solidarity! The police officer told him, "Only Xeysa is serious. Some people complain about her. We are keeping an eye on her. We know that the allegations are not true. Only she is acting seriously and even collecting signatures herself." I collected the signatures with great difficulty. Within a year and a half, I collected 22,500 signatures alone. I was told that I was the first in Europe to collect signatures for Rêber Apo.

This is a photo of Rojda. The middle photo is the last picture of her. This photo shows the comrades she fell with. And here is the notebook she sent to me before she died. A friend brought it to me as a package. She wrote everything in it. She was in the party for about nine years. And she fell.

"Death to Treason"

Do you have anything to say in conclusion?

In memory of Rûken, I congratulate all the guerrillas who are resisting and fighting today in the mountains, in the trenches, in the tunnels, in Rojava, in Shengal. Death to treason! The Barzani family is responsible for the martyrdom of young people every day. It is a puppet of Turkey. Down with the Barzani family! I am talking about the Barzani family, not about the Peshmerga or the Kurdish people in Southern Kurdistan. There are patriotic people there. In Shengal, our girls and women were kidnapped and sold all the way to Qatar. The honour and dignity of the Kurds was sold to Saudi Arabia. This will always stick in our throats as long as we live. Many things have improved in Rojava. We should all feel connected to it. We must help them with all available means. We have 35,000 injured people there. We must help them and show solidarity with them. The occupiers should leave our country and one day we will return home!