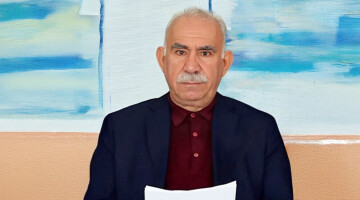

Director Haşim Aydemir said that the Kurds have now entered an active and productive period in many cultural fields, such as literature, politics and art. "There is value. But there are thousands of Kurdish untold stories waiting to be told. These will gradually turn into movies."

Haşim Aydemir was only 9 years old when he watched the films of Kurdish director Yılmaz Güney on the big screen. He entered the magical world of cinema by watching these films. He saw cinema as a magical and influential field. Although his village in the Lice district of Amed, where he was born, was burned down by the Turkish state, he would follow in the footsteps of Yılmaz Güney in Adana, where he migrated with his family years later, to respond to the genocide through art and cinema.

Aydemir, who studied primary, secondary and high school in Adana, graduated from Istanbul University, Department of Journalism. He took his first steps in cinema professionally at the university.

He shot serials such as Ax û Jiyan, Malino, Ref, documentaries and three feature films with collective work. He shot the long features 14 July, and Blackberry Season. Devran in Sur (Pigeon lover), his first black humour feature film, will soon be released.

Director Aydemir was inspired by the stories told by the Kurdish Freedom Movement and successfully adapted these true stories to the big screen.

The stories of the Kurdish resistance and struggle leave their mark on Aydemir's films, who successfully use the story of the Kurdish resistance through metaphor and images through art and cinema.

Lastly, Pigeon lover, shot in Amed, tells the story of three young people named Titi, Dodo and Şaşo.

Director Aydemir spoke to ANF about his bond with cinema, the films he shot and his new projects.

You have been known as the director of films like 14 July and Blackberry Season. When and how did your cinema adventure begin?

As a child, I closely followed the films released in summer theaters in Adana with curiosity and excitement. I used to look at this as a magical space when we went to movie theaters. That atmosphere created in the image emerging from the light and reflected on the screen created a strong love of cinema in me. During the video era, our families secretly watched movies. Years later, I realized that the ones I watched were the films of Yılmaz Güney. The Road, Herd, The Wall and other films... In fact, the nineties were a period when not only Yılmaz Güney's films and thoughts, but also his name, were banned. Yılmaz Güney was serving his own identity and views with his art and cinema. As a person becomes conscious, he acquires a certain knowledge. Yılmaz Güney also gave me the awareness of serving with my identity, my self and art.

I was studying journalism at Istanbul University. My elective course was cinema. There was a Student Cultural Center Cinema Club. There were cinema discussions and movie watching. While I was studying cinema at university, I also carried out cinema studies at the club. After a certain period of time, I focused entirely on cinema. I read stories and wrote screenplays. Most of my research and reviews were directed towards cinema. I had a quest. This search led to the awareness that our age is the visual age and that visuality is to be found in cinema. Cinema had an awareness-raising side, as well as an entertaining side. Therefore, my interest in cinema increased even more. I made short films during my school years. I worked on sets. I concentrated on making my experiences at school and on the sets serve the cinema of my people.

Which directors from Kurdish cinema influenced you the most and how did they contribute to creating your identity as a director?

As Kurds, we started cinema very late. There are movies mainly shot in the 90s. We can see important movies then. Yılmaz Güney gave a great contribution to the establishing of the infrastructure of the Kurdish cinema. The most important point is that movies were made in four parts of Kurdistan, on the mountains, and I watched them all. There is a world of cinema created by Halil Dağ and his friends in the mountains. Halil Dağ proved that cinema can develop in free spaces. He tried to create a language of cinema and art with its minuses and pluses. Halil Dağ's cinema also has an impact and an important role on me.

Yılmaz Güney made his cinematic debut with the Kurdish person turning his camera to himself with his own identity. ‘As a Kurd, I can make a movie,’ Güney said. Before that, the Kurds were waiting as if they were a people waiting to be discovered by someone. Films shot this way were problematic. Yılmaz Güney, on the other hand, captured reality very well and as it is, with art and the language of cinema, when he turned the camera on his own people. Halil Dağ created this war of freedom. He built a pioneering cinema with this freedom struggle. Along with the new Kurd created by the freedom movement in the areas he was in, he also used the power of cinema to present an example of a new perspective for the Kurds through their own identities. There are thousands of filmmakers among the Kurds. In the four parts of Kurdistan, there is also a section that is close to the cinema of the dominant powers and remains passive storytellers and filmmakers. However, with the energy created by the freedom movement, when the Kurds became active rather than passive, they started to show themselves in the cinema. Halil Dağ succeeded in this. The Kurds, who broke their colonial personalities, are creating free cinema. We come across such a process.

Which movies and TV series have you shot? The films you shoot focus more on the stories. Which movie has an important place in your cinema?

We shot the TV series Ax û Jiyan, Malîno, Ref in Amed. In 2012, we shot the documentary Dema Evîn Dikeve Dil about the prisoners who went on death fast. We turned the 14 July [1982] resistance, one of the most important resistances of the Kurdish Freedom Movement, into a movie. We had the chance to film the tortures, inhuman practices and the great resistance of the Kurdish freedom movement in the Amed prison. It was an important film in the history of the Kurdish people. It represents my most important period in cinema. It was the process of my own cinema journey reaching a certain stage. The movie 14 July played a decisive role in my cinematic identity. I think that I have contributed to the freedom struggle of my people through art and cinema. I can say that it is a movie that created me.

This film plays an important role in portraying the resistance struggle of the Freedom Movement, with its own dynamics, filmmakers and artists. The Kurdish people claimed the 14 July film. We watched it in cinemas with the public. We can turn our own struggles and stories into movies, and their feelings and perceptions are formed.

What role did the struggle of the Kurdish Freedom Movement and the Rojava Revolution play in the development of Kurdish cinema?

We can say that the Kurds have entered an active and productive period in many fields such as literature, politics and art. This development was the result of the struggle by the Kurdish Freedom Movement. In a free space like the Rojava Revolution, filmmakers began to produce films and documentaries. The Kurds are now starting to play a leading role. Because world cinema is now in a sort of stalemate. There is a value created by cinema in terms of both the story and the dimension of writing the stories. But the Kurds have thousands of untold stories. These stories will gradually turn into movies. Yılmaz Güney, who took the first step in this sense, brought it to a certain stage. Then Halil Dağ did this in the fields of freedom. Afterwards, dozens of our artists produced films in four parts of Kurdistan and in the diaspora. I think we have brought Kurdish cinema to a certain level through these values.

Blackberry Season is based on a widely read and admired book. How did you decide to shoot the movie? Can you tell us about your shooting adventure?

Blackberry Season has an important place in Kurdish cinema. The prisoner is a true story written by Murat Türk. He turned his life as a guerrilla of the Kurdish Freedom Movement into a novel. When we read it with friends, we decided to adapt this book into a movie. It was a nice story. We filmed a guerrilla's 45-day search for his friends. Erol Balcı wrote the screenplay.

There were guerrilla films shot by Halil Dağ. We watched them. These had an impact on us. The creation of such values in free spaces in difficult conditions created great excitement in us. We asked ourselves why we couldn't make a guerrilla film professionally. We decided to make a guerrilla film for the first time in our region. An artist cannot be independent from his own society and the conditions in which he lives. The 90's were a period in which I was also involved. My experiences were not independent from the experiences of that society. My village was also burned; my brother was a guerrilla. So this story had a sting. These topics were covered in some movies before, but they were covered by others. These embroideries awakened the following in me: If we cannot make our own cinema and tell our own people, no one else will ever be able to do it. Therefore, as an artist and filmmaker, I decided to adapt the realities of my own people for cinema.

What difficulties did you experience while shooting the film?

We were thinking whether we could find the incident in Bingöl, burned villages and mountains in Pencewîn. But we encountered an interesting fact. We saw that many villages in Sulaymaniyah were burned and destroyed by Saddam. In fact, we saw that the Kurds experienced similar events in all four parts of Kurdistan. After the locations and similar mountains are found, we see that the Kurds meet in four parts of Kurdistan. We see that they are always destroyed by the invaders, their identities are denied, their reality is destroyed, and all this is done with oppression and persecution. At this point, the freedom wind created by the Kurdish Freedom Movement had to meet with art. We brought this energy together with cinema. The actors of the movie consisted of some artists from Sulaymaniyah, some artists from the North, mostly the actors in Maxmur Refugee Camp. We also shot with a team made up of people from different nationalities, such as Azeri, Arab and Persian. It was also about our perspective on life. We are a human movement. Therefore, our cinema is also the cinema of humanity. We were contributing to the process of creating our own freedom with cinema.

Blackberry Season was a movie shot in harsh conditions. The movie 14 July was also shot in difficult conditions. But we Kurds have never experienced a comfortable process. We have always lived in difficult conditions. Therefore, we have come to a certain stage by passing through difficult conditions. The important thing is the process of producing these works.

We started the shooting of Blackberry Season in August 2017 and completed it in a month and a half. The subject of the movie was not very independent from the experiences we and the actors had. Villagers living at the location where the movie was filmed suffered similar persecution from Saddam. We all shared our feelings. Everyone from the set worker to the cameraman assistant worked on this film with their own uniqueness. That's why this movie was shot collectively.

What kind of difficulties do you have in bringing your films to the public?

One of the biggest problems of our cinema is the problem of distributing films to the public. The arguments for getting our films to the public are weak. They should be shown in movie theaters professionally.

Where was Blackberry Season shown and where is it showing now?

It was screened in movie theaters in Europe. It will be screened in Rojava in four months. But now there are some festivals held by Kurds, such as Amsterdam Kurdish Film Festival and Paris Kurdish Film Festival. People now follow their own cinema closely. They are happy when they see their own movies. This enthusiasm and energy affects us as well, encouraging us to make other films. Because people support the values we create. We would like to thank the people who watch our films. Our film is screened in many European countries. This movie belongs to people. It will be released in all areas within four months.

You shot another movie after Blackberry Season. What is the story of this movie? When will it be screened?

After Blackberry Season, I shot my third feature film called Devran in Sur in 2019. We show Amed through three characters named Doto, Titi and Şaşo, who grew up with the Qirix culture in the 90s. In fact, we tried to present the experiences of the people in Amed with all the technical equipment of the cinema, in the form of a documentary, through three friends. Sırrı Süreyya Önder and many valuable actors played in the movie. It will be screened in the autumn. I care about this movie too. It is a black comedy. We tried to explain the dramatic world the Kurds live in with a little more humour. To make our people smile. We have a strong people behind us. An artist is successful as long as he does not break away from his people. We do not think that we are going to squeeze ourselves into a tight space and only make festival films. Our only concern is to reach our people wherever they are, by using any means. We try to deliver our films to our people, sometimes in theaters, sometimes in festivals, sometimes on television and sometimes on social media.

Our people supported Yılmaz Güney as well as Halil Dağ. There is a 40-year history created by the Kurdistan Freedom Movement. Thousands of movies can be made from what happened in this history. Kurdish epics and stories should be turned into movies. There were rebellions experienced by Kurds in the 19th century, like the Şheik Seîd rebellion, the Rıza and Ağrı rebellions and more than twenty other rebellions. The Kurds have never bowed to the colonialists; they have always rebelled. As artists, we must rebel with our art. Together with our people, we will turn these stories of rebellion into films. We will continue to adapt both current and historical stories to the cinema. We will continue to reach our people with the movies we make.

Finally, what would you like to say to the audience who follow your films closely?

There are young filmmakers. Cinema is not a place to be afraid of. Filmmakers who will come after us will see our shortcomings and produce stronger films and works. As long as they believe in what they do. We have a great freedom movement behind us, and this movement has energy. The new Kurd is trying to create a model in the world, especially in the Middle East. The movement, which we define as the humanity movement, has also created its own cinema. I believe that we will have dozens of films in the future.