Conference in Brussels discusses the political and social impacts of the 1925 uprising

The conference marking the 100th year of the 1925 Sheikh Said Uprising examined its political, social, and historical impact.

The conference marking the 100th year of the 1925 Sheikh Said Uprising examined its political, social, and historical impact.

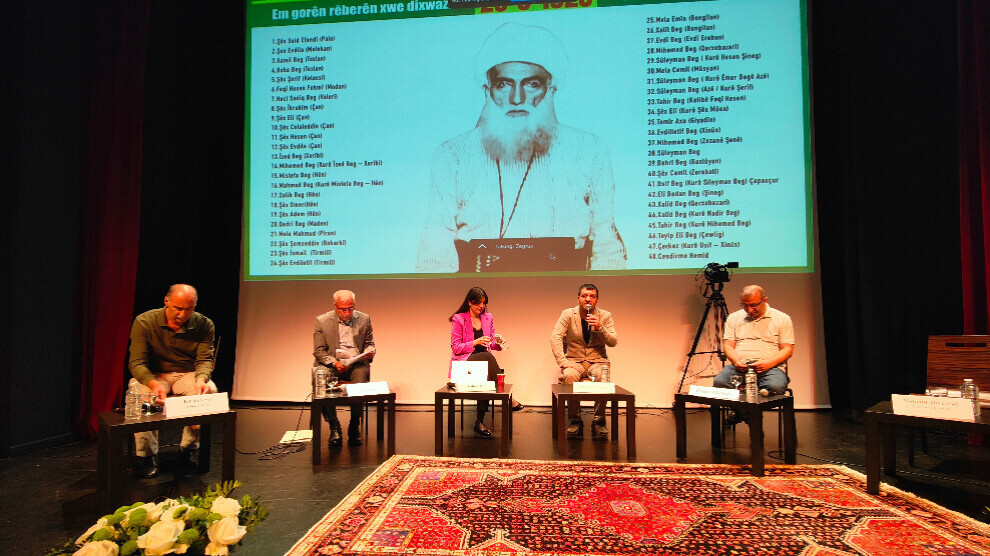

A two-day conference titled “The Sheikh Said Uprising, the Azadî Movement, Sheikh Said and companions, memory and collective opposition in its 100th year” kicked off at Centre Culturel Espace Magh in Brussels on Friday. The conference is organized by the Kurdistan National Congress (KNK), the Kurdistan Islamic Community (CÎK), and the Kurdish Institutes in Germany and Belgium.

Second session

The second session of the conference, titled “The Sheikh Said Resistance (1925 Movement)”, was moderated by Dr. Sedat Ulugana.

The first presentation of the session was delivered by research assistant Kübra Sağır, under the title “An International Perspective on the Sheikh Said Uprising.”

Kübra Sağır noted that the period between 1908 and 1918 marked the development of Kurdish national institutions. She said, “There was a clear distinction between the Kurdish elites in Istanbul and the religious leaders in Kurdistan. In the beginning, cultural and economic demands were at the forefront, but after the First World War, demands for independence and status became dominant.”

Although the Treaty of Sèvres granted limited rights, the Treaty of Lausanne deprived Kurds of all rights, which in turn led to a pursuit of an armed struggle, Sağır said.

She stressed that the uprising developed through local dynamics, and the limited number of documents in British and French archives confirms this.

Contrary to Turkey’s efforts to portray the revolt as externally supported, archival documents from the period undermine this claim, Sağır noted. She stated that Germany sold chemical gas to Turkey, France provided aircraft, and Britain took a firm stance against the Kurds.

Historian and writer Mahmut Akyürekli, in his presentation titled “The Case of the Sheikh Said Movement and the Confessions of Major Kasım,” highlighted that the uprising was organized by the AZADÎ Society.

Akyürekli added that Sheikh Said's court statements also revealed that the revolt was not solely religious but had military and diplomatic dimensions as well.

Akyürekli noted that Major Kasım’s confessions clearly revealed the role of the AZADÎ Society. He explained that court transcripts pointed to a well-organized and premeditated uprising but added that the movement began “prematurely.”

Writer and historian Tahsin Sever discussed how the Turkish state, established after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, was founded on the principle of “Turkishness,” prompting Kurds to seek the establishment of their own state. Within this context, he said, the AZADÎ Society was founded. He explained that following the war waged against the Russians along the Muş–Bitlis line under the leadership of Colonel Khalid Beg Cibrî, efforts to organize around Kurdish identity gained momentum. After holding meetings with Alevi Kurdish tribes, Khalid Beg was removed from his post and exiled to Erzurum, with the official reason being his activities rooted in Kurdish nationalism.

In his presentation focusing on developments in the field, writer Felat Özsoy recounted Sheikh Said’s role in preparing for the uprising and how the revolt spread throughout the region, supported by local testimonies. Özsoy emphasized that the resistance resonated strongly with the people, and the movement was not only religious in nature but was also marked by distinct political and national demands.

Finally, researcher and writer Salih Cemal made a presentation on “The External Dimension of the 1925 Movement”, analyzing documents from French and British archives. Cemal examined how the uprising was portrayed in the international press and what kind of impact it had on global public opinion.

Third session

The third session of the conference focused on the political and social impact of the revolt within Kurdish society. A wide-ranging framework of discussion was presented, covering the activities of the AZADÎ Society, the stance of Dersim, the developments that followed the uprising, and the Ağrı (Agirî /Ararat) Uprising.

The session, titled “The political and social impacts of the Sheikh Said resistance,” was moderated by Dr. Delal Aydin. Kemal Süphandağ gave a presentation accompanied by visuals, discussing the role of the Heyderan tribe in the Sheikh Said Resistance and how this influenced the Ağrı Uprising.

Süphandağ explained that after the Treaty of Lausanne, Kurds began seeking ways to resist policies of denial and destruction. In this context, he said, Colonel Khalid Beg Cibri and various Kurdish tribal leaders organized this resistance. Referring to letters sent by the AZADÎ Society to tribal chiefs to expand the organization, Süphandağ noted that similar letters were also sent to Kor Husên Pasha, the head of the Heyderan tribe.

Süphandağ stated that he had heard this information from his father: “My father, Nadir Beg, told me this. Nadir Beg read these letters to Husên Pasha, who thought that the Kurdish leaders were rushing into an uprising too hastily.”

Süphandağ drew attention to the massacres and forced displacements that followed the rebellion. He stated that Kor Husên Pasha was also exiled during this time, crossed into Southern Kurdistan (Northern Iraq), met with members of the Xoybûn party, and began preparing to join the Ağrı Uprising. He reported that Kor Husên Pasha was killed as a result of betrayal, while his sons, Mehmet Beg and Nadir Beg, actively joined the uprising and fought until the end.

The Republic’s approach to the Kurdish question

In his presentation titled “The Republic’s Inventory on the Kurdish Question,” Professor Mesut Yeğen emphasized that the 1925 uprising marked a decisive turning point for both the Turkish state and Kurdish society. According to Yeğen, this revolt removed any lingering ambiguity for both sides.

According to Yeğen, from the state's perspective, this process marked the beginning of a period of politics based on the denial and assimilation of Kurds with the implementation of the 1924 Constitution. From then onwards, the Turkish state systematically implemented plans and projects that denied Kurdish identity.

From the Kurdish perspective, the uprising provided a clear answer to the question: “Is it possible to walk alongside the Turks, or should a separate path be taken?” A new course was drawn, one in which negotiation was no longer seen as viable, and the pursuit of rights through armed struggle came to the forefront.

Yeğen summarized the Turkish state’s strategic orientation, as outlined in early Republican-era reports, such as the İnönü Report and the Abdi Özmen Report, under three main objectives:

* Turkification of the Kurds

* Establishment of a strong state apparatus east of the Euphrates

* Dissolution of Kurdish autonomous structures and their assimilation and integration into the system

Yeğen stressed that these reports and plans were not merely temporary documents of the time but rather laid the foundation for long-term state policies that were systematically implemented over time.

Migrations and social traumas following the uprising

The presentation titled “Migration to Syria after the Sheikh Said Uprising” by Dr. Seda Altuğ highlighted how the revolt led to widespread state violence that affected not only Kurds but also other ethnic and religious communities in the region.

Altuğ underlined that the repression following the suppression of the uprising extended beyond the participants of the resistance. Communities that had not taken part, such as Armenians, Assyrians, and others living in Kurdistan, were also subjected to this violence.

One of the most visible consequences of the post-1925 wave of displacement, she said, was the forced migration toward the Cizîr region of Rojava, especially to the city of Qamishlo. “After this date, Qamishlo saw a notable increase in population, with large numbers of people, particularly Kurds, settling in the area,” she added.

Altuğ referred to the 1925 displacement of Armenians in the Cizîr region as a “second exile” or “second massacre.” She said: “Following the deportation they had experienced in 1915, they were once again uprooted in 1925. The Assyrians living around Mardin also became victims of these policies of pressure and forced migration."

The presentation also included examples from archival documents kept by France regarding migrants and political asylum seekers in Syria.

Dersim’s stance: the position of Alevi tribes

In his presentation titled “Dersim in the Context of the Azadî Movement and the Sheikh Said Resistance,” researcher and writer Mete Kalman discussed how the contradictions between western and eastern Dersim tribes were exploited by the state.

Referring to the provocative actions of Kazım Karabekir, as documented by Nuri Dersimi, Kalman also spoke about Khalid Beg Cibri and his attempts to build alliances with Alevi tribes.

According to Kalman, in the Varto district of Muş, only the Evdelan tribe supported the uprising, while most Alevi tribes kept their distance and sided with the state. In contrast, in western Dersim, some tribes, particularly the Koçan tribe, wanted to support the uprising. Some members of these tribes traveled to Elazığ and decided to join the revolt, but this decision came too late in terms of timing.

AZADÎ archives and the transition to the Ağrı uprising

Dr. Sedat Ulugana spoke about the archives of the AZADÎ Society, noting that these documents have recently come to light and have been preserved primarily by Kurds who fled to Iran.

Ulugana explained that some Kurdish religious scholars who had aligned themselves with the state before the uprising published documents to manipulate public opinion, and that he had found these materials within the archives. He shared selected excerpts from these documents.

He also stated that between 1927 and 1930, the Kurdish movement in Kurdistan was carried out under the guidance of the Azadî movement. According to Ulugana, this process was reinforced by the relationship between Sheikh Alirıza, the son of Sheikh Said, and Ihsan Nuri Pasha. The leadership of Ihsan Nuri Pasha during the Ağrı Uprising was shaped by Sheikh Alirıza’s counsel and support, he noted.

According to Ulugana, the fact that Sheikh Alirıza stood by Ihsan Nuri Pasha during diplomatic meetings with Armenian parties shows that the Ağrı Uprising can be seen as an Azadî-led organization. Xoybûn only became involved at a later stage, he added.