Power and truth

Analytics of power and nomadic thought as fragments of a philosophy of liberation.

Analytics of power and nomadic thought as fragments of a philosophy of liberation.

Michael Panser, nom-de-guerre Bager Nûjiyan (formerly Xelîl Viyan), was a German revolutionary, who joined the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) out of his determined belief in the possibility of revolution and freedom. He began his political activities at an early age in anti-fascist and revolutionary struggles in Germany. His encounter with the Kurdish freedom movement familiarized him with the philosophy of Abdullah Öcalan. An enthusiastic thinker and activist, Bager Nûjiyan soon travelled to Kurdistan, where he decided to become a freedom fighter and to connect worlds through struggle. He participated in the social and cultural activities of the Rojava revolution, as well as in the liberation of communities in the Middle East, besieged by ISIS. On December 14, 2018, Bager Nujiyan died during a Turkish airstrike on the guerrilla-held Medya Defence Areas in Kurdistan.

A transcript of Bager Nûjiyan’s own account of his political development can be found here

Shortly before his death, he wrote the following letter in honor of the Zapatista Uprising.

We publish a speech of him delivered at the conference “Challenging Capitalist Modernity II: Dissecting Capitalist Modernity–Building Democratic Confederalism”, 3–5 April 2015, Hamburg. Texts of the conference are published as a book.

_

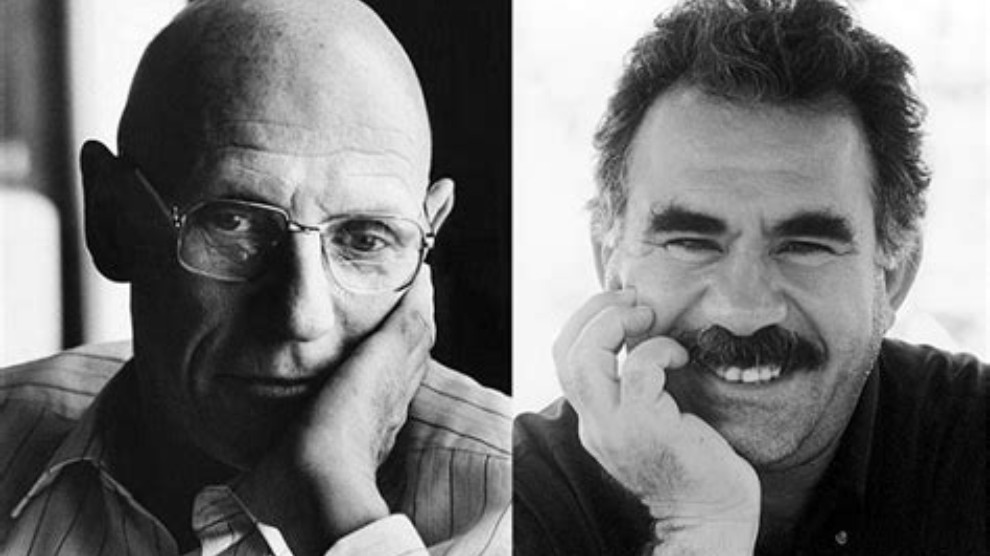

In my studies of the intersections of the philosophical systems of Michel Foucault and Abdullah Öcalan, I mainly focus on three central terms or ideas, which can help us to widen our understanding of the current social situation, of movements of thoughts, and of possibilities to act. I believe that a few mechanisms of thinking, as we can find them in Foucault’s work, could be critical to understanding the new paradigm and the thinking of the Kurdish freedom movement.

The three terms are:

a) system of thought―which Öcalan describes as organized thinking and regime of truth,

b) analytics of power―an understanding of systems and societies and

c) the principle of guidance as practiced by the Kurdish movement―the “rastiya serokatî”, the “governmentality”, as Foucault describes it, through which we can develop a basic understanding of central fragments of the Kurdish movement regarding education, organization and the practice of a democratic autonomy.

Every kind of thought takes place within a specific system, a system of thought. Within this, rational thinking forms the pattern of our perception, the way we grasp the world and organize our daily life. It creates meaning, through which it inspires decisions and forms standards in an ongoing game of experience, criticism and change. Whether we talk about single persons, collectives or societies―every subject carries her experiences with her and, through reflection on her form of life, she is able to effect change. This means each of our actions is based on a certain form of awareness, on the ability to perceive ourselves with regard to reality. Öcalan calls this “regimes of truth”. What we perceive and constantly analyze in order to extract foundations to our actions is an approach to truth; fragments of reality that we experimentally interact with, filter, interpret, and then deem true. Through the differentiation of societies over the past centuries, the diversity of human ways of measuring and mechanisms of thinking―which build the foundation of human actions―have developed into a complex game: a permanent negotiation between different regimes of truth. This means, the variety of approaches to truth and the ways in which subjects structure and change their realities form the foundation of social diversity and creativity.

What could political theory be, then? The attempt to question one’s own subjective and collective frame of meanings, to move it, if necessary, and to reveal possibilities for action: a toolbox, experimental and always connected to one’s intentions. This more or less summarizes the way Öcalan shows us possibilities to interpret history and to creatively and fragmentarily write the history of our present.

Every kind of thinking―and, through it, political theory―that dedicates itself to the necessity of social change, is strategic. Our thinking cannot be separated from our power to act, from our ability to change reality through purposeful action. So, there is a connection, a triangle, a field of tension between knowledge, power and truth. This is one of the central arguments that Foucault developed in his works. Based on an understanding of a given situation we are able to perform a series of actions. We can use our own power to act, to shift our own relation to reality, and to effect movement and change. Every subject has the ability to act purposefully within its own frame of perception. It can change the situation within its own system, or it can move the frame of its own perception and, through this, its own possibilities of action through critique and theoretical reflection: a transcending way of thinking that moves one’s own position: nomadic thinking, organized thinking―at this first point Foucault and Öcalan complement each other and translate themselves into one another.

That means (and here we are moving on to the second idea) that we have to give up an old notion that weighs heavily on the mental horizon of the West: power as something negative, as purely suppressive, as the pole of evil and as the sovereign rule from above. Here, I refer to central thoughts Foucault has carved out. They underlie Öcalan’s thoughts often implicitly rather than being written out in detail. But the consequence that he suggests with his new paradigm of democratic confederalism operates in the same system as Foucault’s methodology. At different points he refers directly to concepts that have been developed by Foucault in his conception of power――for instance the concept of biopower, as one of the most important pillars of capitalistic rule. A part of Öcalan’s thinking is based on such an analysis of power. This kind of thinking is also the foundation of other world-views of quite similar shape, starting with the indigenous cosmovisions in Latin America (e. g. the Zapatistas), Zarathustra and the thinking of far eastern world-views, that do not know an object: thinking of heterogeneity, change, connectedness and subjectivity.

Then, what is power? Power is not simply the great other that is facing us, the king, the police(wo)man, God. All those are effects of a concentration of power, more or less symbolic, with different ways of interpretation to reality. Power by itself is neither good nor evil. Generally, power describes the possibility of a subject to move within a system, to create frames of meaning and to act on them―thus, agency on the one hand. On the other hand, today’s societies are marked fundamentally by power; they organize themselves along lines, hegemonic ambitions, accumulations of power, accesses and structural shiftings of the power of definition. Every subject has the capacity to act. Power evolves from every part of society, it pervades and structures society. To cite Foucault―power is the field of lines of force that populate and organize an area. Power is not something you gain, take away, share, that you keep or lose; power is something that is implemented from innumerable points in the play of unequal and flexible relations: the omnipresence of power. Power is above all the name given to a complex strategic situation in a society. It is an meta-understanding of mechanisms of power relations that Foucault provides to enable an analysis of the society which reveals possibilities of action.

This way we can grasp dominance as a concentration of power at a certain point within a system. A part of, or a point in the system―the human being, a party, a state, a man or any institution―creates a frame of meaning, which, if it is not accepted, might be answered with exclusion and/or aggression. Dominance means to deny to other parts of the society the power to act, partly or as a whole, or to take it from them by force and, by this, make them objects, victims of their own decision without any further negotiation. To implement dominance, means and tactics are necessary to effectively separate the subject from its own truth and its own vitality and to gain control over it this way. Dominance develops when the others’ power of definition regarding their own form of life and their own decisions, their ability to define their own necessities, is effectively disturbed. Dominance means the divesting of power of the dominated. But because power is never separable from one’s own knowledge―and the ability to act is closely connected to the consciousness of the world, the access to truth―a project of dominance must strive to implement its own regime of truth as an absolute, normative and only acceptable standard of truth. This makes up the project of the state and the patriarchal gesture. The form of interpreting history proposed by Öcalan tries to name this project of disempowerment of societies, to create ways of access to truth and make resistance strategically organizable: To use Foucault’s words―Society Must Be Defended.

Where there is power, there is resistance, too. Resistance always forms a part of power relations, because no kind of dominance can become absolute, even though its claims may be real. The relations of power are strictly relational, which means that they only exist between subjects. The game of power, resistance, negotiation and fighting is a process, a steady flow of elevation and decrease of positions. This game cannot come to an end, except through the extinction of the Other―which means the collapse of the system. And as dominance―like the state―depends on the control and arrangement of power relations, the strategic codification of points of resistance can lead to revolution.

We are not located outside of the power dynamic. Our consciousness and our form of life represent attempts to follow our demands and to become an acknowledged part of society: we become subjects through the power, within the social matrix of powers.

A society without dominance doesn’t need to fight a liberational war against an enemy opposing it (although self-defense might be necessary), but to empower itself. Here we find a central argument of Öcalan’s new paradigm.

So what is opposing this? We have to confront the issue of governance, which is the third point I wanted to mention. What is a state? The state only exists in practice―In other words: through the people that act according to its principles. This is where Öcalan’s conclusions about the process of civilization and Foucault’s understanding of subjectivation―that is to say: turn into a self―agree, each from a macro- and a micro point of view. The state is not one single institution; it is not one large machine that consists of administration, police, justice and military. These are forms which the state adopted, effects of truth or strategic measures, so to say. Rather, and above all, the state is an idea, according to which human beings act and put themselves in relation to reality. The state is ideology, “weltanschauung”. This perspective on the state is the foundation of Öcalan’s proposals for a democratic socialism and of his view on societies that oppose the state and that fight a war of defense against the grip of the state.

What does the pattern of the state work, its access to reality? Foucault identified strategies and “dispositives” that build the framework of state power and control, and he explains how these measures were constructed by the state in the first place. Here, he applied his concepts of governmentality―the art of governing. Earlier I mentioned the complex of power, knowledge and truth. It is within this complex that we have to imagine the principle of guidance that the state represents and establishes.

First, as a system of thought: The state’s regime of truth―its relation to reality―leads to reification, control and mobilization: Creating hierarchies, restriction, separation, scarcity, dominance of rationality and functionality as well as the great systems of dichotomies: homogenization and exclusion, normality and state of emergency, private and public. The state is mobilization, organization through pressure and externalized guidance――alien leadership.

Secondly, centralization of power. The state rests on an idea of a great central power around which everything else is organized and structured. For a long time this used to be God, later a king, and with the development of capitalism it transformed into the principle of “practical constraint”, which mobilizes and manifolds the center; a totally unitized system in place of God. It is the central mechanism, which is being followed by every movement, which acts according to the state.

Thirdly, the state commands by effects of truth that penetrate and structure everything: state architecture, strategic dispositives like the system of prisons, the medical complex, bureaucratic administration, police control systems, the public. In the ideology of the PKK, this technology of the state as a whole that serves the fainting of society is called “şerê taybet” which means “special warfare”. These are war tactics that establish the truth regime of the state and attempt to destroy all other ways and possibilities of thinking. This works through the introduction of influential paradigms: Consumerism, nationalisms, militarism, hostility, liberal and feudal personal patterns―widely implemented forms of socialization. All of these are mechanisms in which the system of thought called “statehood” is working in the society.

So we can conclude the following: The state is a certain way of regarding the world via absolutethinking, dogmatics, law and reified regimes of truth in the form of epistemic monopolies. The state is centralization and organization―that means control―of social negotiations through subjection of the other. The state is leadership through disempowerment, relinquished leadership. Here capitalism and the state don’t oppose each other. Capitalism is a version of state-led governmentality, the extension of the state’s dominance and productivation through to the most basic parts of society. Today, lines of power transgress the bodies’ inside and principles of the states’ leadership have devolved upon our consciousness and our actions. Capitalist modernity, coming from the west has, through the imperial extension of their own conception of the state’s leadership, managed to establish a transcending guidance over societies and individuals―of their ways of thinking, their ways of acting, their desire and their forms of becoming subjects.

What does all this mean in regard to social practice, for a project of liberation from capitalist modernity? A society that wants to free itself from the state has to create a real socialist governmentality in opposition to the state-led one. This is what in Öcalan’s philosophy is called Rastiya Serokatî: The principle of right guidance.

And, in Foucault’s sense, we can interpret this on all levels: As a process of social organization, in which democratic mechanisms of decision-making and tools of mediation are created, which are based on recognition of plurality and participation, and on social ethics. Guidance also implies a self-empowering way of living, as a development and evolvement of one’s own perception and power to act.

I want to claim that the new paradigm―the utopia of democratic confederalism―is the project of such a socialist governmentality, and thus a real possibility to take back social life and varying forms of life from the capitalist modernity. Similar to the principle of the Zapatistas in Mexico, it is about the project of the “good government”, which lacked the past socialisms: a self-government, self-administration of society beyond the state.

The socialist governmentality, as Foucault says, is not set up in the socialist writings of the 19th and 20th centuries―it still has to be invented. The truth about leadership, as Öcalan puts it, and the practice of democratic autonomy, form an attempt to implement this experiment.

Those who want to lead themselves need to philosophize; those who want to philosophize need to deal with the truth. Therein, I believe, the essence of the mobility and the strength of the movement and the philosophy of Öcalan can be summarized. It is a form of nomadic thinking, as Foucault calls it, a critical-subjective, self-reflective access to the truth based on multiplicity, solidarity and social ethics. Most importantly, the new paradigm led to a socialization and collectivation of philosophy and tools for self-awareness. What is impressively shown to us in Rojava is the very well working academy system. Each social group organizes itself based on concerns, working fields or identity and has its own academy, with Öcalan’s epistemology as an important part. Thereby, a society creates its own framework of significance beyond the influence of a state. The struggle for self- liberation through the understanding of one’s own situation and history, one’s own possibilities and will, as well as desires, is a fundamental component of a socialist project. Especially for societies in Western and Middle Europe, this awareness is of particular importance as the dominance of the state is more deeply anchored in the collective world view of the citizenry and the resistance is organized less powerfully. All the fragments of state-centered thinking need to be found and opposed by organization: Organization of thinking, which means flexibility of methods, self-awareness and ideology; becoming aware of one’s own mobility, creativity, power to act; and self-guidance through de-individualization of meaning and organization of decision-making.

Source: Komun Academy

RELATED NEWS: