Since the 1980s, thousands of people, mostly Kurds, have been considered "disappeared" in Turkey. The country became familiar with the practice of "disappearances" after the military coup of September 1980. In the mid-1990s, when the Turkish state's dirty war against the PKK was particularly bloody, this method reached its peak. It is estimated that more than 17,000 "disappeared" by "unknown perpetrators-that is, by parastatal and state forces-during this dark period under Prime Minister Tansu Çiller, who were buried in mass graves, caves, or in disused industrial plants, thrown into garbage dumps, sunk in well shafts and acid pits, or, as in Argentina, disposed of by being dropped from military helicopters. Often they had been picked up at home by the police or the army, or they had been ordered to the local police station for a "statement", or they had been detained during a street check by the military. This is often the last thing their relatives know about the whereabouts of the missing persons. Most of the victims of "unidentified murders" can be attributed to JITEM. This is the name of the informal secret service of the Turkish military police, which is responsible for at least four-fifths of the unsolved murders in Northern Kurdistan and whose existence was denied by the state for years.

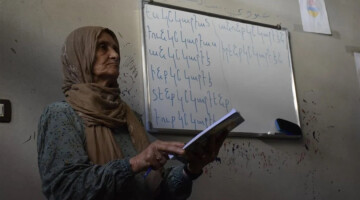

Synonymous with the fate of the disappeared are the Istanbul Saturday Mothers, who since 1995, analogous to the Argentinean "Madres de la Plaza de Mayo", have been protesting week after week in Istanbul in sit-ins with pictures of their relatives against their "disappearance" and demanding clarification of their whereabouts. On the occasion of the International Day of the Victims of Disappearances on August 30, also known as the Day of the Disappeared, the initiative, in its now 805th action this Saturday, called on the government, in particular President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, to end the injustice done to the Saturday Mothers and to give them certainty about the fate of their family members. The vigil took place virtually again due to the pandemic and was opened with a speech by Jiyan Tosun. She was only six years old when her father Fehmi was dragged into a car and kidnapped by police in October 1995. Since then he has been considered missing.

"The Turkish state refuses to sign the UN Convention against Disappearances. This has to do with the fact that it does not want to come to terms with its past. It does not want to face the crimes committed under its responsibility. Instead, the actors from back then are being covered up," said Tosun and vowed that they would continue to fight until those responsible are brought to justice and held accountable for their crimes.

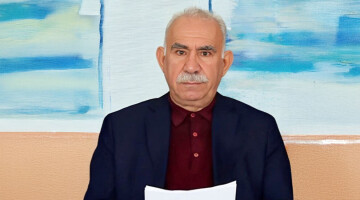

Hasan Karakoç, a brother of Rıdvan Karakoç, who disappeared in February 1995 after being brought to the police and whose death by torture came to light only by chance, said: "Those we lost were fathers, brothers, husbands, friends and relatives. They were taken from their homes or cars, from the streets or from buses by state forces and disappeared by torture. Most of them do not even have a grave. We as their relatives and survivors are dominated by the pain of not knowing what happened to our loved ones. Our lives revolve around the question where our loved ones are. Our demands are clear and precise: The state must clarify the fate of the disappeared.

The insecurity of not being able to know the truth, the waiting caused by this insecurity, the deep emptiness created by the failure to achieve justice, makes the lives of lost families hell, Fatma Şimşek said. Her sister Ayşenur, a pharmacist, was kidnapped by the counter-guerrilla in Ankara in January 1995. Despite all efforts and numerous requests, there was no official information about her whereabouts. The security authorities did not acknowledge her arrest, although there was an arrest warrant against her. Four days after her abduction, a disfigured corpse was found on a roadside in Kırıkkale, about a hundred kilometers away.

"We call on the judicial authorities to be independent and courageous, to prosecute those responsible for disappearances in police custody and to end the current impunity" said Şimşek and continued: “They must take practical measures against these serious violations of human rights. Most importantly, however, the state must sign and ratify the UN Convention on Enforced Disappearances without delay".